The Psychotronic Tourist: “DEATHLINE” (1972)

In anticipation of Kim Newman’s upcoming lecture at The Miskatonic Institute of Horror Studies – London this coming Thursday (April 9th – details HERE), which will get knee-deep into the production history and political subtext of Gary Sherman’s beloved 1972 horror film Death Line, the Psychotronic Tourist comes back after nearly a year hiatus (our last installment being Possession in February of 2014!) to look at the various locations that make up Sherman’s subterranean masterpiece about the last in a line of cannibals descended from Victorian rail workers who were buried alive when constructing London’s tube system.

Sherman referred me to the film’s First AD Lewis More O’Ferrall to verify some of the locations, but even between the two of them some of the locations (the bookstore, the pub) remained a mystery, with only vague recollections of where they may have been in (the bookstore possibly on Museum Street, the pub viagra online without a prescription possibly in a since-razed area of York Road in Battersea). My own research and extensive google streetview-mapping turned up nothing that matched (anyone with a line on either of these locations please let me know so I can update!). To create the article below I spent many, many hours comparing tiling, brickwork and windows in order to cull together any locations that the filmmakers couldn’t recall (it was over 40 years ago, after all!), so below is a survey of the film’s locations that remain and can be visited by curious movie tourists, followed by a handy map.

And the best part is, if you come to Kim Newman’s lecture at Miskatonic London (which is housed by The Horse Hospital in Bloomsbury), you’ll be passing right through Death Line’s main location to get there.

++++

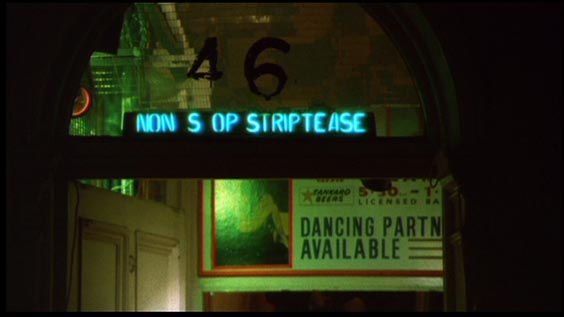

Strip Clubs – 37 Berwick St and 46 Old Compton St, Soho

Both Sherman and More O’Ferrall have said that all of the strip clubs from the opening sequence of Death Line were in the area of St. Anne’s Court in Soho, including the Queen’s Exclusive Striptease at 37 Berwick St and the Star Striptease Cabaret at 46 Old Compton St, which actor James Cossins is seen exiting. There were nearly 60 sex shops in the surrounding area by the time of Death Line’s filming, as well as the members-only Compton Cinema Club, co-owned by Tony Tenser, producer of Polanski’s Repulsion, and Michael Reeves’ The Sorcerers and The Witchfinder General, among others. “St. Anne’s Court was, and still is, a narrow walking street – no vehicles – that winds its way from Wardour St. to Dean St. in Soho,” explains Sherman. “Back in the 60’s and early 70’s, and probably earlier, it was Soho’s “red light district”. Lighted doorbells labeled “Monique – French Model”, “Cynthia – English Model”, “Svetlana – Russian Model”, etc., were plastered around every doorway leading to the steps that went up to the apartments above. Between these doorways were a scattered selection of sleazy strip clubs. But that wasn’t all… Soho was the center of the London buy levitra by mail film and commercials industry, so, in juxtaposition the strange little street also housed a couple of the best sound and re-recording studios in London. One of those was World Wide Sound where also every foreign film was dubbed into English and vice-versa.”

37 Berwick Street in 1972 (photo from flashbak.com):

37 Berwick Street in the film:

37 Berwick Street now:

46 Old Compton Street in the film:

46 Old Compton Street now:

Subway Station Exterior – Russell Square Tube Station

Located in London’s Bloomsbury district – once a hotbed of literary talent and only steps away from the 18th century Horse Hospital that was rechristened as an arts venue of the same name in 1992 – Russell Square tube station was designed by architect Leslie Green (who designed at least 29 of the original tube stations, most recognizable by their blood-red brick, semi-circular windows cialis online us and patterned tiling) and opened in 1906. While Russell Square is the primary tube location of the film, it is really only the exterior that is used; the actual subway platform, stairwell and lift are filmed in Aldwych Station (more on that below). Geographical license allows for the lecherous character played by Cossins to turn the corner in the heart of seedy Soho and end up at Russell Square Station, but this is only one of the film’s many clever co-minglings of fact and fiction; Russell Square is near to the British museum, which allowed for director Gary Sherman to create the fictional “Museum Station”, under which we find the cannibal’s lair.

Russell Square Station in the film:

Russell Square Station now:

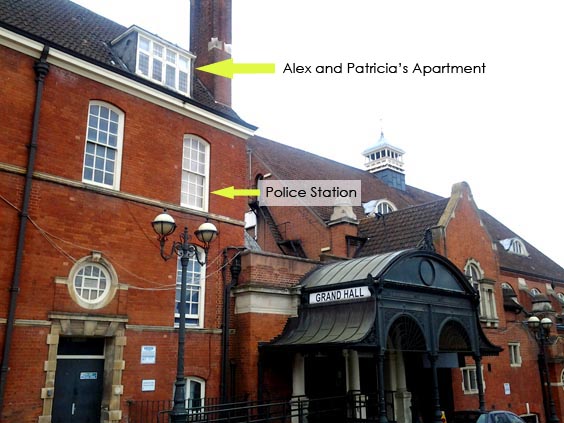

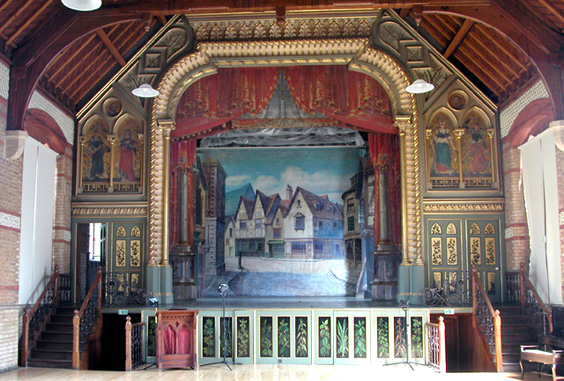

Police Station/Apartment Interior/Theatre Exterior – Battersea Arts Centre, 176 Lavender Hill, Wandsworth

“This, like Patricia and Alex’s flat, was “built” in the old Battersea Town Hall,” says Sherman. Opened in 1893, “it had just ceased being a Town Hall when we shot there.” The rooms used for the police station are on the second storey, on the Town Hall Road side of the building boasting the ornate Grand Hall entrance (which doubles as the film’s ‘theatre’ where Patricia and Alex come out from a show, walking past a poster for Donald Swann of comedy duo Flanders & Swann, then performing as a solo act). Two years after Death Line’s release, the building was converted into the Battersea Arts Centre, and became a location in Richard Loncraine’s Slade in Flame (1975). Like both tube stations used in the film, it is a Grade II-listed heritage building (a designation admittedly bestowed upon over 300,000 buildings in the UK and which even includes things like the Beatles’ Abbey Road pedestrian crossing) – but less than a month ago – on March 13, 2015 – it was severely damaged in a massive fire that completely destroyed the Grand Hall, the Lower Hall, and possibly the offices that served as locations in Death Line. The front of the building was preserved, and fundraising efforts are in place to rebuild the halls. (To donate click here: https://www.nationalfundingscheme.org/BAC012#.VRylUuFFW-X)

Grand Hall Theatre entrance in the film:

Grand Hall entrance now (before the fire):

Police Station in the film:

Apartment ‘set’ in the film:

The Battersea Arts Centre fire (photograph by Rex):

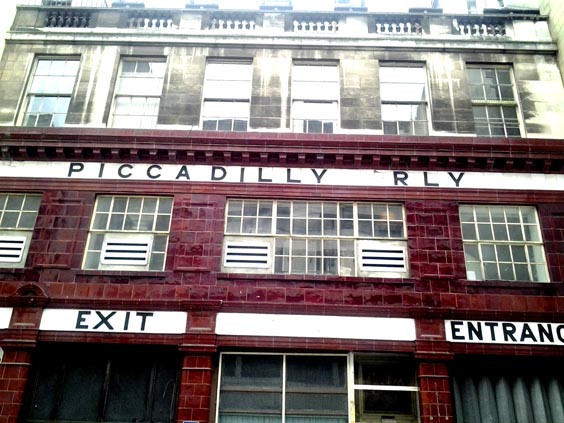

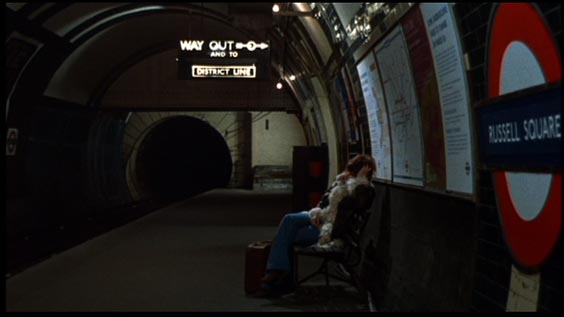

Subway Platform – Aldwych Station

The confusing history of several tube stations is a big part of how the tube geography of Death Line could easily lend to its adoption as urban myth. Despite the exterior of Russell Square Station being used as the cannibal’s main conduit to ‘above ground’ civilization, the platform itself was filmed at the now-disused Aldwych Station, which sits beneath the intersection of Strand and Surrey St.

As with Russell Square Station, Aldwych was designed in the iconic red brick style by Leslie Green. Originally called “Strand Station” when it opened in 1907 – as it was built on the site of the demolished Strand Theatre – it was renamed Aldwych in 1915. Its original name can still be seen on the entrance facing Strand, and on some of the platform walls. “Aldwych was only used for the comings and goings with live tube trains,” explains Sherman. “In order to be allowed to shoot there at all we had to submit a really bad, never-produced script for a spy thriller that we re-titled Treason for Sale. There was no chance that London Transport ever would have let us shoot Death Line down there.”

Aldwych Station entrance on Surrey St., 2013:

Strand entrance, 2013:

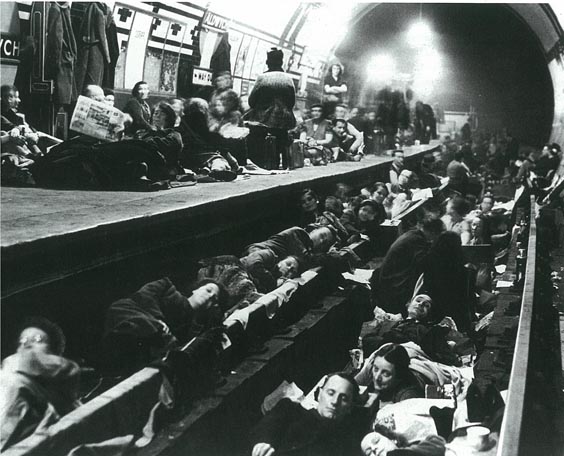

Aldwych was an odd station that essentially served only a shuttle train between two stops – Aldwych and Holborn. With several plans for extension successively aborted, the station became increasingly avoided by passengers in favor of other connections. During WWII the station was closed for six years and used both as a storehouse for valuable artworks from the National Gallery, as well as a bomb shelter that housed thousands of Londoners during the Blitz (which brought its own problems of ventilation, sewage and illness spread by mosquitos). By the time of Death Line’s filming in 1972, Aldwych station was only being used during weekday peak hours, which made it a popular location for filming. Death Line was only one of many films to shoot there (including Christopher Smith’s own Death Line riff Creep in 2004). As an added bonus for filmmakers looking for a creepy setting, the station is reputedly haunted by the ghost of an actress from the original Strand Theatre that stood on the same spot.

Aldwych Station during the Blitz:

When asked how the real history of the stations may have played into his creation, Sherman says, “It’s all made up! Although I did a great deal of research to learn the history of the tube, everything in the film was born in my demented head, with a lot of help from Ceri Jones, my equally demented writing partner.”

Still – It’s interesting that the film creates this alternate history of the London tubes. Not only does the use of Aldwych station bring its own pop-cultural baggage about people being ‘holed up’ in the tunnels, but geographically, the abandoned fictional “Museum” station appears roughly where the real-life disused “British Museum” station sits. Part of the reason for the series of disused stations throughout London is that the different tube lines were originally built and operated by different companies. While they would often try to collaborate in creating connecting platforms to accommodate travellers, sometimes there would be redundancies; British Museum station opened on the Central Line in 1900, while Holborn opened on the Piccadilly Line in 1906 only 100 yards away, and in a much better location for transferring to above-ground tram lines. As a result, British Museum station closed in 1933, the surface station demolished in 1989 and the remaining tunnels are now used solely for storage. This kind of muddying of fact and fiction is part of what gives Death Line such credibility despite what could otherwise be seen as a far-fetched storyline.

Aldwych station has been permanently closed since 1994, although seasonal tours allow visitors to explore its underground history.

The Aldwych Platform in the 1950s:

The Aldwych platform playing “Russell Square” in the film:

Aldwych Stairwell as seen in the film:

Aldwych stairwell now:

Cannibal Lair and “Museum Station” – Bishopsgate Goods Marshalling Yard, Shoreditch

The cannibal’s underground lair, and the adjoining “Museum Station” were filmed in the extensive underground section of the abandoned Bishopsgate goods marshalling yard belonging to British Rail. “It was bang in the centre of Shoreditch,” More O’Ferrall explains, and parts of the bricked exterior are still visible today, where the 5-acre area is undergoing extensive rejuvenation. “The storage area had been used to build the tubes since Victorian times,” Sherman adds, “then used to store military goods during WWII. It remained British Rail property when London Transport was formed [in 1933]. I had seen this place before writing the final script and actually adapted the script to make the location work with very little scenic change other than extensive set dressing. The fight scene (in the dark) was done at the abandoned tunnel location because London Transport would not allow any violent scenes to be shot on their property.”

“That whole area, like so much of the more run-down parts of London, has been redeveloped and tunnels don’t exist anymore,” says More O’Ferrall. After being derelict for over 50 years following a fire in 1964, and with parts of the original yard’s heritage-designated exterior gates still covered beneath tarps and scaffolding when I visited in 2014, the whole grounds have been gutted and are gradually being turned into condos, offices, shopping and public leisure areas – a redevelopment that has caused protest by those who see the large scale plans – which include 40-storey condo towers – as being at odds with the historic aspects of the neighbourhood, in particular its mixed-income demographic. Read more about the development plans here: http://thegoodsyardlondon.co.uk/about

The Goodsyard / “Museum Station” in the film:

The Goodsyard/”Museum Station” in 1995 (Photo by Nick Catford):

A large concourse in the goodsyard in 1995 (Photo by Nick Catford):

The same concourse in development today:

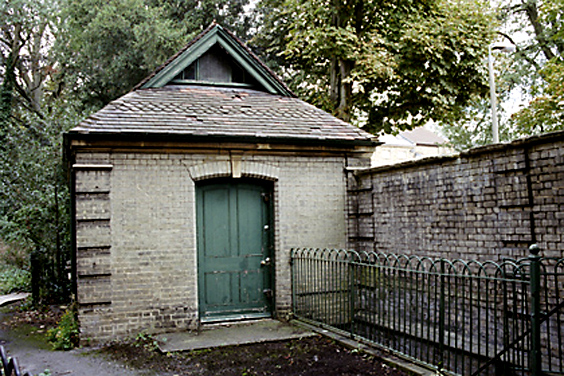

Morgue – Normansfield Hospital Mortuary, Teddington

“Not many out of town locations on Death Line but this was one,” says More O’Ferrall. “If my memory serves correctly, we shot in an actual morgue which I think was in Teddington and, though I can’t be certain, it might have been the Normansfield Hospital.”

The mortuary at Normanfield Hospital still exists and is easily accessible, as it is located right along Normansfield Rd against the outside wall. But from the exterior it is hard to tell whether or not the tiny building would have been the morgue location used in Death Line. The windows certainly don’t match, and as a Grade II-listed building, it wouldn’t have been changed.

The morgue in the film:

The Normansfield Hospital Mortuary exterior:

But assuming O’Ferrall is correct – and that perhaps the morgue is somewhere else on the premises – the Normansfield Hospital makes an interesting choice of locations, especially as the sprawling hospital was in period of scandalous decline at the time of filming. It was opened in 1868 by Dr. John Langdon Down (after whom Down’s Syndrome is named) as a private asylum for children with developmental disabilities, and named ‘Normansfield’ in honour of the solicitor who helped them secure the mortgage on the large estate – which then consisted of a large mansion and five acres of land (the grounds grew to comprise 32 acres). It was originally called the Normansfield Training Institution for Imbeciles, and was renowned throughout most of the next century as a caring, family-run institution that gave true quality of life to children and adults who had previously been locked away by their wealthy families (the admittance fee was £200 per patient, then an extraordinary amount). The hospital even housed a lavish theatre, built in 1879, in which the staff performed plays and recitals, sometimes involving the patients themselves.

The Normansfield Theatre:

But by 1970, Dr. Norman Langdon Down (grandson of the hospital’s founder) retired, and the private hospital had been integrated into the National Health Service who appointed Dr. Terence Lawlor – a psychiatrist who has been described by past nursing staff as “deliberately perverse and cruel,” – as head of the institution. The hospital’s reputation sharply declined; the facilities were filthy and patients were not properly cared for and rarely allowed outdoors; as a result the nurses went on strike in 1976, prompting an investigation that resulted in Lawlor’s dismissal. (There is an ongoing oral history of Normansfield posted at https://normansfieldhospital.wordpress.com/.

The entire site was bought in 1999 and parts of it were redeveloped into the Langdon Park housing estate, although many buildings on the premises remained derelict for many years (see some great urban explorer pics here: http://opacity.us/site149_normansfield_hospital.htm ). They also restored and re-opened the hospital’s amazingly-preserved Victorian theatre as the Langdon Down Centre, which is now owned and operated by the Down’s Syndrome Association.

Normansfield Hospital in 2006 (photo by “Rookinella” from the UE site 28dayslater.co.uk)

Café – The Moulin Rouge, 245 Shaftesbury Avenue

Earlier in the evening before Patricia gets abducted by the cannibal, she and Alex have a meal at a crowded café in Soho’s bustling theatre district. “This was a restaurant at the top of Shaftesbury Avenue,” says More O’Ferrall. “It was owned by Cat Stevens’ father.” It was also where Cat Stevens had lived until only two years earlier, and where he would occasionally still wait tables. There were entrances on both New Oxford Street, and Shaftesbury Avenue, the latter seen below. In the 70s (post-Death Line) the Moulin Rouge was renamed Stavros (Cat Steven’s father’s surname) and has since gone through many incarnations – it was re-opened in 1994 as Alfred’s, later as Nama, and later still as The Shaftesbury Bar and Dining – but is currently partially vacant, with a fancy Turkish barbershop running out of the New Oxford St. entrance.

Moulin Rouge Exterior, 1950s:

Moulin Rouge exterior, today:

Moulin Rouge interior in the film:

Interior, as the Shaftesbury Bar and Dining:

Apartment Exterior – Grafton Mansions, Dukes Road, Bloomsbury

This 1890 Victorian building replaced older buildings in what was meant to be an exclusive residential area; Dukes Road was gated until 1840, with residents having to show a silver ticket to gain access. In an attempt to maintain the neighbourhood’s status as a restricted upper class suburb, residents found themselves “with the task of preventing, or at least discouraging, the conversion of dwelling houses into private hotels, boarding houses, institutions, offices, and shops” (Donald Olsen, Town Planning in London, 1984) But its proximity to several tube stations come the turn of the century – Euston, Euston Square and Russell Square – as well as the increase of institutions in the area, including University College London (opened 1826), made this a losing battle as it allowed for more access to transient communities. Still, the ten apartments that comprise Grafton Mansions are quite large, which was an attempt by landowners to appeal to a ‘higher class’ of resident.

Grafton Mansions in the film:

Grafton Mansions today:

This latter point is somewhat fitting considering Death Line’s political subtext; Grafton Mansions is one of two Death Line locations that in real life, were meant to be reserved for the rich (the other being Normansfield Hospital). When I asked Gary Sherman to elaborate on the ways the tunnels are used to explore the history of social stratification in the UK, he said: “I was a dyed-in-the-wool left-wing hippie back then (still am, minus the Jimmy Hendrix hair-do). After several attempts to sell scripts that openly promoted my political views, I decided to hide those tenets behind the cover of a horror film. It worked! It took a while before anyone realized that Death Line was my rant about racism and the class system.”

Sherman’s tack worked; genre fans universally laud Hugh Armstrong’s performance for giving us one of the most sympathetic villains in horror history – diseased, hated and lonely, his last words the only ones he knows: a mangled version of “Mind the doors!” Sherman always intended for him to be a tragic figure, the unnamed, unknown casualty in a centuries-old class war. “The ‘man’, as he was called in the script (and in the titles), was – like many real people in our society – not responsible for being thought of as a monster by those who were allowed to live up above in the sunlight,” Sherman says. “He only did what circumstances forced him to do to survive, like many real people in our society have to do.”

Sherman’s anti-authoritarianism is what led him to emigrate to the UK in the first place, where he funded Death Line with the money earned from a rather famous commercial job: the New Seekers’ “I’d Like to Buy the World a Coke” ads. At the time there were incentives for American directors to make films on UK soil, but Sherman’s motives for moving were more political than financial. “I left Chicago and moved to London following the 1968 Chicago Convention,” he recounts. “My mother was British, which afforded me the opportunity, and I felt it was more possible to express my beliefs from there than in the late 60s USA. I remained in the UK until Nixon was no longer in office… enough said?”

++++

Special thanks to Sean Hogan, who is always roped into being my London psychotronic touring buddy, and thanks to Gary Sherman, Lewis More O’Ferrall, Simon Murphy and Emily Cartwright of the London Transport Museum and the Subterranea Britannica website for helping me put the pieces together.

April 6, 2015

April 6, 2015  No Comments

No Comments