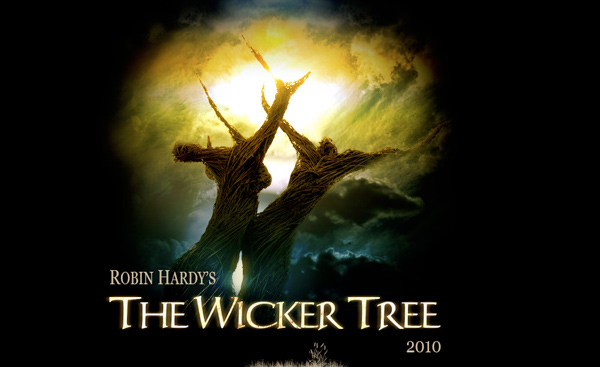

Robin Hardy on “THE WICKER TREE”

A SUMMER TO ANOTHER SUMMER: Robin Hardy Talks about his WICKER MAN companion film THE WICKER TREE

Kier-La Janisse

———————

Back in 2000, I made a pilgrimage to a small town in the Scottish Highlands called Plockton, a tiny village along the Northwest coast where the palm trees lining the water’s edge seem strangely out of place – especially as I had to traverse through snow-covered hills to viagra canada generic get there from Edinburgh. Three trains and 6 hours later I arrived, and found a town oddly untouched since the time of The Wicker Man’s filming almost 30 years earlier. Walking into the local pub, it was like that famous scene in An American Werewolf in London: all the customers stopped dead mid-conversation and turned around to online pharmacies uk selling levitra look at me as I entered. I was handed a glass of beer bigger than my head and, after a pause, the bartender quipped, “you must be a Wicker Man fan.”

And that I was, having travelled all this distance with the hope of finding the Harbour Master’s boat, that little red and blue rowboat with the eyes painted on the front, which had been brought over from Malta by a migrant fisherman and immortalized in the film. Supposedly the online levitra us boat still existed, and was sitting in an abandoned shed in the forest outside the town. I was referred to a local named Callum McKenzie, who gave me some convoluted directions as to how to get to the shed: walk around the inlet to the castle, take a left onto a wooded path, climb the fence, cross the railroad tracks, and there I would find the Harbour Master’s Boat. Seeing my worry at being able to successfully navigate the way, he halted a passing motorcycle and asked the driver – whose face was covered by a giant black helmet – to drive me to the castle. I hopped on the back and we drove there in silence; he left me at the castle and drove off – and I never saw his face. I remember thinking that this situation could have turned out quite badly for me, but travelling sometimes calls for unordinary trust in strangers.

I walked through brambles and bushes, climbed the fence, crossed the tracks, and there it was – an old decrepit boathouse with four disused rowboats sitting inside. On the far right was the Harbour Master’s Boat. “Okay, I’m here,” I thought to myself. “Now what do I do?” Realizing there was no way I would be able to actually take the boat out onto the water, I instead opted to sit in it and eat a sandwich. Then I made the long trek back to town, back to the train, and back to Edinburgh. I still don’t know what prompted me to take such an epic journey for what amounted to maybe 10 minutes of sitting in a moldy old boat covered in weeds and cobwebs, but there you have it. That’s what obsession is all about.

The Wicker Man had a strange effect on people. Although it would categorized as part of what has been referred to as the folk-horror mini-boom of the early 70s (Blood on Satan’s Claw, The Witchfinder General ), The Wicker Man is an entity unto itself. Its power as a film, a story, a window into a fictional world based on ancient truths, is ineffable. So when Robin Hardy, the director of the original Wicker Man, announced that he would be making a long-awaited follow-up film, based on his novel Cowboys for Christ, fans were waiting with bated breath.

The Wicker Tree is the darkly comedic cousin of The Wicker Man – although certain thematic preoccupations remain, this is a new film for a new era. Woven through with ritual and song, it is, like The Wicker Man, a story of death and rebirth. A story of fools and surrogates. A colourful and enthralling vision of old time religion gone wrong – for the right reasons.

I’m sad to say the Harbour Master’s boat didn’t survive, having recently been destroyed in a storm. But the legend of The Wicker Man lives on through The Wicker Tree, and Robin Hardy was kind enough to share a few words on the eve of its premiere.

————————

Had the idea for the book Cowboys for Christ (on which The Wicker Tree is based) been gestating for a while after the original Wicker Man, or did something inspire you to pick up the story again and write another exploration of pagan-Christian relations?

I was surprised that no-one had tried to make a film that blended sex, songs, comedy, romance, a serious discussion of the metaphysical and ultimately horror. [The Wicker Man] broke all the rules of the horror films of the time and, indeed, we thought of it as a black comedy. A film fantastique. When an influential film magazine labelled it ‘The Citizen Kane of Horror Films’ we were, of course, flattered – but it didn’t make The Wicker Man a horror film as it was understood in the 1970s, still less today. Dog Soldiers is a modern horror film and the two genres (a comparison with The Wicker Man or The Wicker Tree) are as far apart as Brief Encounter is from a Tarantino movie.

In addition to the clash of religions, there’s also a clash in their approach to religion – one group clearly proselytizes more than the other. What is continually appealing about pitting these two religions against eachother?

What is interesting to me is not the antagonism between Christianity and Paganism but how similar they are.

Are you a religious person yourself?

I am clearly very interested in religion and it’s continuing effects on mankind (the close similarities between extreme fundamentalist Christians, ultra orthodox Jews and Wahabi islamists for instance) in the face of a Mount Everest of scientific facts. I am not personally religious although I sometimes think of all sentient things from peach trees to killer ants as DNA cousins of mine.

Are there communities in the UK where remnants of the Sulis-worshipping practices are still in effect? Is there actually any history of human sacrifice, like there was with the Gauls and the wicker man structures? What are the links between the religions in the two films?

Pan theistic beliefs were and are similar all over the world. Our celtic ancestors, who occupied or conquered the whole of western Europe, believed in a kind of cabinet of Gods with defined roles. In Rome they believed Mars did war and Venus did love. Gods did no-one any favours unless it was paid for with a suitable gift.

The Wicker Tree is more overtly humourous than The Wicker Man – even though the latter had humourous elements, they were comparatively played down. What prompted that decision?

I wouldn’t agree that the humour is played down at all. But a lot of it is ironic humour, the humour of incongruity and of pathos. Also plain old fashioned wit.

Both Lord Summerisle and Lachlan Morrison in The Wicker Tree are suspect characters but also are very nurturing in their own way – in what way are these characters representative of authority figures in general, in a religious or secular sense? You’ve described Lachlan as a ‘dictator’ before.

Both Summerisle and Lachlan were waspy patricians. Their authority was tinged with paternalism. One suspects they read classics at University. They knew what was good for everyone and insisted, where possible, on sports for young men. Did they believe in the pagan faith themselves? Lachlan says: If I am a Rabbi, Jehova is my God. If I am a Mullah, Allah the merciful is He. If a Christian, Jesus is my Lord. Here in Tressock, I believe that the old religion of the Celts fits our needs at this time.

What do you see as the major differences between the devout lead characters (Sgt. Howie and Beth Boothby) in both films?

I don’t see that much difference between Howie and Beth, faith is faith after all, but there is a difference between warmly believed – in morality, even if it has been learned by rote, and, on the other hand, humourless sanctimony. But both Christians are, in their different ways, martyrs to their faith and cause.

Tell me about the role music plays in both films. It’s a rather persuasive tool.

The music, as often in Opera, carries the narrative forward and is a little like dialogue only much more beautiful and emotionally charged. It helps create the joie de vivre for which, along with the humour and seductive sex, a horrific ending is a shocking anti-climax. On Wicker Tree. I commissioned Keith Easdale to write all the songs, leaving him to choose the best versions since many are traditional. We both contributed to some of the lyrics. On Wicker Man I chose most of the songs from the Sharpe folk song collection in London. Peter Shaffer un-bowdlerised them and Paul Giovanni provided many of the melodies.

Why do you think The Wicker Man has the kinds of devoted fans that other occult films of that era (like Blood on Satan’s Claw etc) do not have? Wicker Man fans are a rather fervent bunch.

I think as Christopher Lee says of The Wicker Tree (aka Cowboys for Christ): “It is erotic, romantic, comic and horrific enough to loosen the bowels of a bronze statue.”

I read in an interview that you also design historical theme parks. Can you tell me a bit about that? Where are they?

We are creating the first of these for Iceland. The Spirit of Scotland in West Lothian will hopefully follow.

————–

THE WICKER TREE will have its World Premiere on July 19th at 9:30pm in the Hall Theatre, with director Robin Hardy and actor James Mapes in person. More info on the film page HERE.

July 19, 2011

July 19, 2011  No Comments

No Comments