FANTASIA 2017: “UN PEU APRÈS MINUIT”

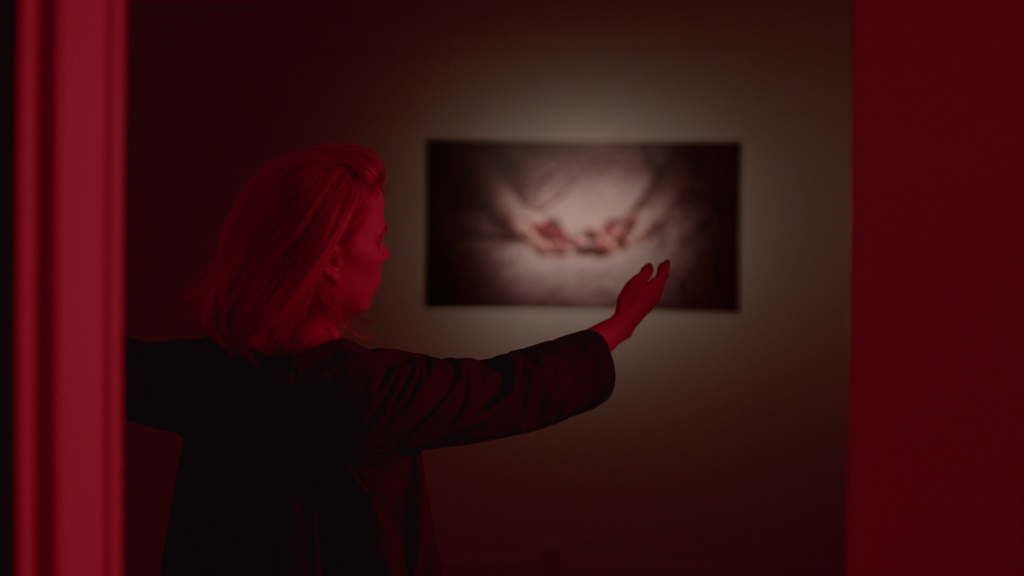

Throughout cinema, there have been few representations of the blind where they are given agency, power buy levitra online viagra and community. Anne-Marie Puga and Jean-Raymond Garcia’s short film UN PEU APRÈS MINUIT, which opened the second edition of the Fantasia Film Festival’s BORN OF WOMAN showcase celebrating women directors, fills this vacancy. The film pushes things even further by giving our main character and the blind community she is part of predatory tendencies.

In a small countryside town, Suzanne (actress India Hair, also seen on Fantasia screens in JACKY IN THE KINGDOM OF WOMEN in 2014) is a blind professor working at mastercard cialis an elementary school. As the story progresses, the viewer gets a sense of an ominous determination in Suzanne. She uses her disability to get what she wants, and to take advantage of her devoted assistant (Rémi Taffanel). Suzanne pretends to be incapable and canadian needs a prescription in us unaware, and transforms into a menacing personality.

Garcia and Puga’s knowledge of art history persistently creeps perfectly throughout the film, coupling this primal tale with striking imagery. Together they conjure up a gorgeous, haunting world, pushing past stereotypes and tropes—such as the wise and all-knowing blind person—to create a deeply unsettling atmosphere.

Esinam Beckley: In this film you’ve chosen to have the blind community represented by being powerful and having a sense of that power. How did this idea develop?

Jean-Raymond Garcia/Anne-Marie Puga: We wanted to demonstrate the power of a group, of a community. That’s the basic concept. There are two things. From the opening scene we can see the shadow, the outline of the whole group going into the building, then we see the conference room. This idea comes from being in a group, that you are not alone. In regards to Suzanne, we wanted to deliver a very clear idea of a heroine who is extremely determined to get what she wants. She is blind, and she is determined to take a pair of eyes. We wanted to display her as a predator.

EB: Throughout cinema many representations of the blind are usually that they are wise and all-knowing, but not necessarily predatory. Why did you choose to display this aspect in particular?

JRG: When I was a student I spent a year with a friend who was blind since birth. I spent a lot of time with him doing crazy things. I really had no sense of his handicap. We went to the cinema together. We went after the same girls. We drank, we smoked. We did normal things together. For me he was a normal person, not really handicapped. We wanted to show this idea through Suzanne. Like yes she is blind, but we wanted to give this power to a blind woman. Showing that she does not need to succumb to circumstances.

Many films show blind women as fragile and vulnerable. This is not necessarily the case. People with a handicap are vulnerable in a sense, but at the same time powerful. They can be powerful, energetic. Also, with many films Hollywood has portrayed blind people as having no knowledge of their charm or femininity. This is really important. Suzanne has knowledge, and is aware of her charm.

EB: During the Q&A at Fantasia, you mentioned during the making of the film, you worked with an all blind cast of actors. At the last moment you had to change your actors to people who could see. Why was that?

JRG/AMP: In the beginning we had 36 blind people to make the film. In the final scene of our original story, we had children with masks accompanied by their parents. A kind of Sabbath. Suzanne sets up the Sabbath, and the small blind community surround the parents of the children, and take their eyes. With the children as accomplices.

We had meetings with our blind actors to discuss the scene. Some of the actors also had guide dogs, adding a bestial kind of quality. All the blind actors were ready, and willing to work with the scenario.

Eventually, we were astonished to find out that the organization which gave us money to make the film, did not like the idea. This organization did not agree with the acts in the film, which could potentially deliver an extreme message. This is something that surprised us. Such conformist, conservative, judgments against the film. One of the heads of the blind association read the scenario, and he found it pornographic. I had a meeting with this head of the association. What’s funny is that he is not blind! The people who make these decisions for the blind are not even blind. That’s a scandal in itself. They said no, we cannot allow this. We no longer want blind people being part of it. In turn, this intimidated the blind actors that were working with us. It made them uneasy. We filmed this in the town of Limoges. There was a blind actor who told us that if we were in Paris, which is a much bigger city, this would not have been so dramatic, not such a problem. It was really discouraging. We lost 36 blind actors and we had 48 hours to change the casting. We recruited 15 new people and gave them lenses.

Also, the other organization in charge of working with child actors believed the scenario to be too explicit. When we did this scene, the organization thought it gave the children a very inappropriate idea of how things should be. They feared that the children would be partaking in a kind of satanic act that they did not fully understand.

EB: What was the process of casting your 2 main actors, India Hair and Rémi Taffanel?

JRG/AMP: We were at an exhibition in Paris that paid a kind of homage to François Truffaut. We watched young actors/actresses interpret some of his work. After watching India Hair’s interpretation, we were very impressed. She had great skill. After having watched her, we immediately wanted to communicate with her, to see if she was interested in the role of Suzanne. She read our script and was very interested. She accepted. With Rémi Taffanel we saw him in a film that was done by Damien Manivel. Remi played a role in that film that was amazing.

Rémi is interesting because he does not really have a modern physique. He gives us an impression of someone in between the past and modern times. He is passive, clumsy and awkward. He is a bit aloof, absent minded. It was important that while playing the role of Pierre, he did not give out an energy of any negativity. He’s clumsy, but he is gentle, and innocent. This was very important for us. One of our favourite scenes is when he is on the phone with Suzanne and she asks if the girl outside is more beautiful than her. He responds to her and says I prefer you. I remember Anne-Marie and I on the set said to Rémi: “You are 14 years old and you’re in love with a girl, but you’re shy. You don’t know what to do, or how to act. You don’t know how to declare your love.” He acted this out exactly. This is what he conveys in that scene. He is such a talented young man. In the beginning it was much longer, so we had time to work with him and develop his personality. Because of what happened, and lack of funding, we had to make it much shorter. We had to make sure the principle ideas of his character would be shown. He is a gentle, soft, tender guy. It was a bit complicated having to develop that in a shorter time period. We had less scenes to express these ideas. We needed someone to deliver those ideas thoroughly, and quickly. As opposed to Suzanne who is predatory. He is the complete opposite of that.

EB: What are your personal and artistic inspirations for this film, and otherwise?

AMP: It’s important to combine two universes. I’m more experienced in contemporary photography, painting and sculpture. I try to combine all these things together to get my inspiration.

JRG: I watch a lot of film, but the most important thing to me inspiration-wise when starting this project was to find my childhood experience of cinema. I had a desire to rid myself of the cerebral, theoretical quality of my cinematic experience. I wanted to lean more toward primitive things, naïve things. Also, Anne-Marie introduced me to Cindy Sherman. I didn’t know about her before. Anne-Marie showed me a universe that I could identify with. This was very inspiring. We also had in common love of architecture.

EB: There is a scene where the blind community is gathered in a kind of greenhouse. One of them tells a joke/lurid short story to a non-blind person, who becomes upset by the menacing behaviour he is experiencing. Where did this story come from?

JRG: A woman from the ministry of culture told me that story! I couldn’t believe my ears. I thought it was absolutely crazy. So we included it in that scene. We also looked at a lot of photographs that deal with paranormal activity. Photographs from the early 19th century. We put a lot of the ideas from those photographs in that scene. We wanted that ceremony scene to show that Suzanne is the leader. She is the source of inspiration for the blind. We wanted to give her power to the community too. When we were editing we were looking for sounds. What you hear in that scene is actually an African hyena, and the frogs are African frogs. I was so obsessed to get a sound of a universe you can recognize, but you’re not sure of. That was very important for us. Sound is everything, and music, we can talk for hours about music.

AMP: During the scene we were really laughing. A sordid story like that is fabulous for the audience to enter into their world.

EB: Occultism, paganism, witches, feminism and ritual seem to be strong elements in the film. Are these topics important for you?

AMP: These kind of ideas have been interesting to me since my childhood. My grandmother, who was Spanish, was very superstitious. For example if someone in the family had a stye in their eye. My grandmother would carry out a kind of ritual. She would pile up these little stones and put them outside somewhere. The moment a stranger would knock over the stones. According to her, the stye would then be transferred to that person. When my grandmother was carrying out all these little rituals, me and my brother would hide and just watch, totally fascinated. So these ideas were in my childhood.

EB: I love that kind of naturalistic, simplistic, but powerful imagery.

JRG: Yes, well speaking of the subject of simplicity, nature and power, another thing which was inspiring to us in regards to the children in the film was a collection of photographs of children in Halloween disguises from the 1920s and 1930s.

AMP: Yes, those are photographs from a book by Ossian Brown.*

JRG: Yes, Ossian Brown. In the book the disguises are extremely simple. This extreme simplicity provides us with a sinister like quality. The photographs are terrifying. But yes, this dimension of naivety, primitive/primal things, and paganism. The pagan rhythms usually move in accordance with nature. Primitive things. These were important aspects to us.

Also in regards to witchcraft–I became very interested when reading about the Loudun witch trials. An incredible topic of 16th century France. Loudun is a small village south of the region where I grew up. I discovered that the bottom line of these trials was the persecution of women. Society is always dominated by males. I just never realized how much masculine domination was exercised through superstition, through fear, to control women. I really wanted a heroine who was looking for control, and that for me was really important. Also, when we watch the film I’m not sure if it comes through. But her aid Pierre, he gives himself to her. He gives up his control. He sacrifices himself to her. He gives his eyes. He lets this happen.

EB: Yes! He doesn’t struggle. He doesn’t scream. He gives himself to her?

JRG/AMP: Absolutely. Before Pierre in the film, all the masculine personalities are duplicitous, or physically dominating, very masculine brute type of men. Everything that I detest. It’s important to have Pierre as a personality who does not exercise control over others. It was important to have a woman who has power, and who will take power. In the end Pierre recites text from THE DYING ANIMAL by Philip Roth. The passage is very erotic. Almost pornographic. Because of Pierre’s personality, he is able to transcend this, and it becomes poetic. The final scene is a double initiative. Suzanne to take his eyes, and for Pierre it is his first sexual experience.

Extrait "Un peu après minuit" from Uproduction on Vimeo.

+++

*Editor’s note: Ossian Brown is an English artist and musician known for his work with Coil and Cyclobe, both with his partner Stephen Thrower, who is known to horror fans for his books NIGHTMARE USA, BEYOND TERROR: THE FILMS OF LUCIO FULCI and more.

August 8, 2017

August 8, 2017  No Comments

No Comments