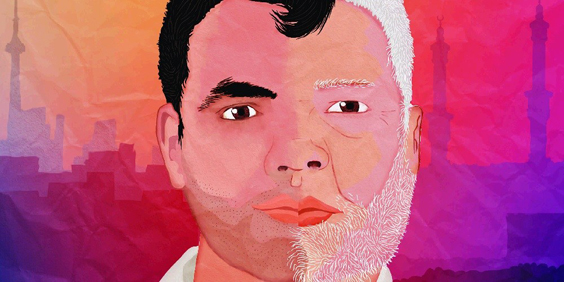

Fantasia 2017: Director Arshad Khan on “ABU”

Sexuality, immigration, religion, family, trauma, love, racism – director Arshad Khan’s debut feature ABU perfectly captures the complexities of pills store buy levitra human life.

Coming of age is always awkward. But being a gay man, immigrating to a new country and having a conservative father where to buy propecia will undoubtedly exacerbate this awkwardness. ABU is a highly personal documentary that depicts Arshad’s relationship with his father (Abu is the word for “father” in Urdu) and the world around him, which is fascinating and cruel. It’s the kind of up close and personal film that often feels like you’re being let in on a secret.

Combining animation, clips from classic Indian films and VHS family footage, Arshad recounts his story in a way that often seems like fiction, with a daring openness and vulnerability that provides an outstanding depiction of a human life. Visually and narratively, the film plays with the viewer’s emotions in a beautiful way.

An unforgettable experience at this year’s Fantasia Festival, ABU canada cialis is essential viewing if you are a human who cares about other humans.

Esinam Beckley: How did the idea for ABU start and/or develop?

Arshad Khan: I came to cinema as you see in the film pretty much after 9/11. I was really fed up with the way things were, and I felt that this association of my identity with terror is not acceptable to me. The media wasn’t doing anything to counter that, and it really upset me when I saw how it was affecting myself, my colleagues, my friends and my family.

I think that Canadians or people who are born and raised here, they don’t quite understand the trauma that is migration. In this film I try to show how global movement of canada cialis no prescription people affects people and families. How it affected my family. How these people need a lot of TLC. They need a lot of understanding, you know? It’s not an easy choice to make. When you make it, you do it for whatever reason – safety, security, education, economics – but it’s a hard choice.

So you’re asking why I decided to make this film. I was trying to make a fiction film. All student filmmakers want to make fiction films. Those are a whole other beast. You need a lot of resources and a significant amount of money to start those projects – for development, production and post-production. I realized in 2011 while I was working on a big feature (a gay love story set in Pakistan) that my father got sick, and he died. I decided that I was going to make a five minute video memorial. When I was making that film, I realized that I had such a wealth of material that I could use to tell a story, and maybe I should look into it. So we made a three-minute teaser for Cuban Hat – you know, the RIDM competition? It caught a lot of attention and I was very afraid. I was like oh my God, I’m outing myself, and how are people going to feel? People really connected to it, and that really encouraged me. Then I ended up getting a Canada Council Grant. That was amazing. So I had to hire an editor and start working on something. I worked with Etienne Gagnon, who is this brilliant editor and he was so selfless in his dedication, his love for my film, for me, and for the project. So that’s how we got started.

EB: A lot of your experiences are simultaneous opposite emotions. Childhood innocence paired with a block of personal space. First love, paired with an immediate deprivation of it–and threats. How do you decide, with such tumultuous history, what goes first, middle and last in the narrative?

EB: A lot of your experiences are simultaneous opposite emotions. Childhood innocence paired with a block of personal space. First love, paired with an immediate deprivation of it–and threats. How do you decide, with such tumultuous history, what goes first, middle and last in the narrative?

AK: That was very complicated–deciding what to put in, and where to put it, without it appearing cheesy, tacky or self-pitying. Without it coming across as contrived; it was very challenging. That’s the whole challenge of filmmakers, especially documentary filmmakers. Because in documentary you have to be honest. You have to be fair, but you also have to be entertaining and light-hearted about it, in a sense. So when you’re making a film about yourself, it’s so much more complicated. That’s why I’m happy I had co-writer friends helping me. These people helped me formulate the story, and it got better all the time. My editor helped me move the film in the right direction, and I rewrote the narration many times. He’s a very strong writer. I worked with images and narration to weave the story, and put in exactly how much was needed.

Another challenge is exposing a person. I love this person that I’m talking about in my film. So I did blur his face out. We didn’t want his identity revealed, because we didn’t want him to be endangered. I didn’t want to ruin the memory of us together, you know? I still did want to tell the story, so I did tell it, and I think that it’s important. Stories of queer love are buried. Stories of queer love are discouraged. Especially in my culture. The making of the film is a miracle because all the odds were stacked against me as a Pakistani Muslim person. To make a film that is so exposing of me, my family and my culture.

EB: In the film you finally come out as a gay man. This is a huge and extremely personal moment for people in real life. Not only that, but there is a lot of suffering that you have bravely put on film for everyone to see. How has it been editing, and having to relive these moments over and over?

AK: That was awful, let me tell you. I was crying a lot. The first few times I told my editor, these are the videos, this is the writing, I cannot watch it, you have to just do it yourself. Every time I would do it, and record the narration, I would break down. It was very hard, and the molestation scenes, when I talk about them, I also cried. I couldn’t stop crying, so we just kept me crying, and sobbing. We just used that as a narration until eventually–after hundreds of recordings–I was finally okay and calm. Calmly able to deliver those lines. It’s very difficult. Those are difficult places to revisit, and when I watch it with an audience it’s very emotional. When you watch it with an audience, it’s a very different experience.

EB: You have such an innocent and yet all-knowing approach. Like a wise old child. How did this develop?

AK: Ha ha ha! I’m a bit of a man-child. Unfortunately or fortunately. It comes with a lot of problems, but your observation is correct. I have always had this thing that I think I get from my mom. This curiosity I’ve always had. That spirit of learning. Finding new things. New adventures. I’ve always been adventurous, and willing to go to new places. Having a pioneering spirit, that was my mother’s thing that came out in some of us. Leading the way, and being curious. Having a curious, questioning mind. The other side of it is you don’t believe a lot of things that people tell you. You question everything. As children who survived sexual abuse that gets intensified, because you have a hard time trusting people. You have a hard time believing them. You’re more intensely emotional. You take things personally. That kind of a personality type comes with baggage. You learn to manage those things, that’s how I am. The film was therapeutic. I seek therapy trying to become a better person, and I try to cope by not letting people suffer because of my man childness.

EB: What was it like using animation to tell your story?

AK: Animation was so hard! I worked with the animator Davide DiSaro. He’s a very good artist. A brilliant artist. I’m pretty sure I frustrated him, because I didn’t have that much money. You can only have so much footage. I had a wealth of footage. There were just some things that I couldn’t use the footage for, which I really wanted to show the beauty of. The first time I was in love. The feeling of the train ride. Coming out to my dad. The absurdity of that situation. My father’s dream, things like that. So I was like how am I going to represent them? With my animator, I was able to put something together. In the beginning, it really looked very Beavis and Butthead-y. It took years. Literally. To keep going back to it. He kept telling me you have to do it this way I kept saying no I want the visuals first and then I’ll put words to it. It was back and forth. A lot of negotiation. Animation is very difficult. Every second of it cost money, and my collaborators were very generous. I have a new respect for animation after working with it.

EB: How did you choose the particular style of the animation?

AK: He and I just kept working on it. What age to show. How to show it. The opening animation for example. How much to show. What to show. We just kept massaging it. Making it better, layering it. You have to understand that one of the most important parts of an animation, is not the visual part. It’s the audio part. Sylvain Bellemare came on as a sound designer. He and I then created this beautiful soundscape, which really reinforces the animation. You don’t realize it, but it really brings out the animation, and works in cohesion with it. It makes all the difference. When the sound design came in, it really popped.

EB: In the film we see an evolution of yourself. Innocent Arshad, angsty teen Arshad, comfortable-in-his-skin Arshad. There are many different stages. What was it like witnessing your own evolution?

AK: Ever since I was a child I hated seeing myself. I did a lot of destroying my photos. Recording over my videos like I did in the VHS. I erase myself from the videos. I was doing that stupidity a lot actually. I hated seeing myself most of the time. I became comfortable with it working on this film. Getting comfortable in your own skin is not an end in itself. It is a process. You just learn to fake it better. When you have that you just have it. You learn to cope with it. You learn to reject yourself better. Those demons return. You can’t get rid of them. It’s very hard. I didn’t want to dwell on negativity in my film. I didn’t make it so dark. There was a time when there was a lot of darkness in the film. We decided we weren’t going to do that. We decided against it. Already the film is hard. It is hard. It is emotional. People are very moved by it. I just didn’t want to go towards devastation. I wanted to have hopefulness, but I clearly hinted at the demons that were faced at these traumatic events. Some cope with it in different ways. Some get over it. Some don’t, and this film is the tip of the iceberg.

EB: One of the descriptions you use for yourself is cinema junkie. What are some of your film inspirations?

AK: I’ll tell you what inspired this film. What I took references from to help me make the film. To better get ideas. Jonathan Caouette’s TARNATION. It uses VHS archives. Beautiful film. STORIES WE TELL, a Sarah Polley film, and MEET THE PATELS, a film by Ravi and Geeta Patel.

My film has a fiction treatment. I don’t know if you realize that. It’s structured as a fiction film. It’s not structured like a typical documentary film. I could do that because it was my story. My film. So I was able to have that. As far as my life influences go. My influences come from very varied sources. In Pakistan we only had one TV station. The TV station was incredible. It showed American shows. British shows, Australian, Russian, Polish Chinese. I grew up with the very international cinema experience, which is not what people can say about Canada. Of course the Pakistani and Indian movies I grew up with as well. A real variety of influences when it came to cinema.

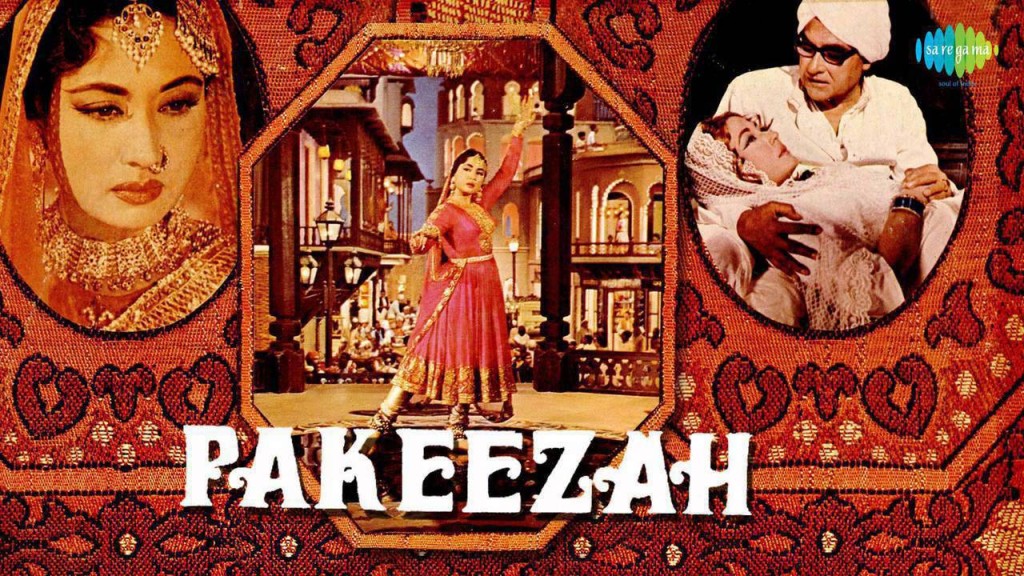

EB: The clip that is shown when your sister is talking about what your mother was like is stunning, and moving. Which film is this clip from?

AK: PAKEEZAH. A beautiful and important film. My film is very layered. There’s a lot of meaning behind things in the images. There’s a lot that I’ve said, but there’s a lot that I have not said. It’s one of those things where I’m saying a lot about my family, about their past, and about us. About what we loved to do and that is an iconic film. A very important film. A very tragic film. It’s a beautiful story that my sister tells about my mother. A beautiful moment.

EB: In the film after a visit to the library, you are greatly impacted and talk about the huge difference an act of kindness can make in someone’s life. Can you talk about that?

AK: A library is a place of sanctuary, you know? That’s the reason I put that in the film. It was so important for me. Librarians are such important people. They’re educated people. They’re good people. She helped me so much by just that small gesture. Just putting the book there. She said, “Young man, you might enjoy this book.” Then she left. She didn’t say a word or anything else. I looked at the book and I was like, oh my God, and I signed it out discreetly. I was like, does she know anything about me? I hardly know her. She liked me because I was a really polite person. I used to always come and say hi, go into the library, and say goodbye. Nobody else did that. These are just the kind of manners that my family grew up with. I think she just liked how polite I was.

EB: There is an incredible scene where you are on a talk show, upset, and clearly articulating your ideas about war.

AK: Thank you, that was a very important show. It was the eve of war. The 19th of March. I’ll never forget that evening. I was shocked at these people, who were just speaking of war as if it were liberation! I’m like, you’re fucking morons! This is the worst idea! And everything that we were warning about, everything came true. Because these people are full of lies! It’s awful. That’s why this is a testament and you know that show I was on, CounterSpin? CBC cancelled that show because the advertisers pulled their support, because it was so critical of war. It was a very very good show, you were probably too young when it came on. It was very hard for me to get a hold of those tapes.

EB: In many ways this documentary can be viewed as a romance. A romance between you and activism. Between you and country. Between you and your father. Do you feel the documentary is a romance?

AK: It’s a love story. That’s actually an observation that experimental filmmaker Mike Hoolboom had. He said this is a surprising love story. And it is. It’s about finding love. It’s about finding a place to call home. At its essence, it’s a love between father and son. It’s a love between men. It’s a love between nations and people. India was divided by the British. Brutally. Split into two. People don’t understand that. They don’t realize that Pakistan and India were part of the same country once. There’s this horrible animosity between the two nations. Even though I start with this positive thing about the Army. I’m super critical of the army, the institution, and these programs of War. I’m super against them. The film is extremely pro peace and extremely anti-war. I needed to do that. I needed to make a film that was so clearly, passionately, anti-war, and speaking about how war destroys people and how war affects us.

++++

ABU has its Canadian Premiere on Sunday July 16th at 2:00pm at the Fantasia International Film Festival, in the DB Clarke Theatre. More details HERE >>

July 15, 2017

July 15, 2017  No Comments

No Comments