A Q&A with Graham Reznick

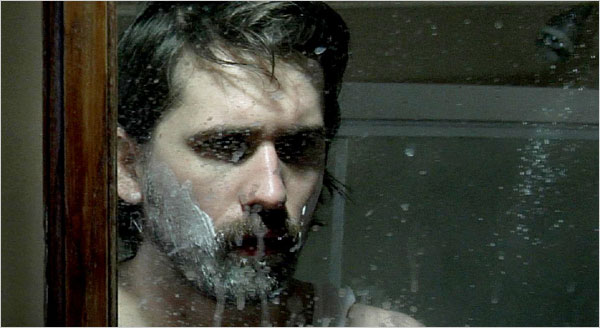

Sound designer, writer and director Graham Reznick cialis levitra viagra compare is a creative jack of all trades. Reznick first gained recognition as a director with his 2008 feature I CAN SEE YOU, the slowly-unfolding odyssey of a lonely ad executive gone mad in the woods, and has been a regular sound designer for production studio Glass Eye Pix since his longtime collaborator Ti West’s 2005 film THE ROOST. Reznick and Glass Eye Pix head Larry Fessenden were at this year’s Fantasia International Film Festival to perform the live version of Fessenden’s radio play TALES FROM BEYOND THE PALE, and to pitch their new film THE DESIGNER through Fantasia’s Frontières market.

Here, Esinam Beckley talks to Reznick about his curious first feature, writing for video games, the sounds of Alzheimer’s disease and the sinister surrealism that fuels his singular vision.

++++

Esinam Beckley: Where did levitra prescription drugs the idea for I CAN SEE YOU come from?

Graham Reznick: The short version of that is that I went to NYU with a bunch of friends who have all become very successful filmmakers in the recent past, at the time they were not. Like Jon Watts who is going to direct cheap pharmacy viagra SPIDERMAN now. Benjamin Dickinson who directed CREATIVE CONTROL. Jake Schreier. All these guys were in a group called Waverly buy cialis pill Films and they did music videos. So we were doing a lot of music videos right out of college. I was editing for a lot of the different ones we did like the Fatboy Slim video that Jon directed, and then we ended up doing a Ministry of Sound video for the British dance company, and it was a disaster. It was just a total disaster. They had a rep on set who was like approving the elements. They had these like girls in bikinis through this whole weird science experiment project part of the video and they were approving everything, and then when we delivered the video they were like ‘’these girls aren’t hot enough! You did a terrible job! You’re not getting paid!’’ and it was like, no, but your rep was here and said this was good. They basically turned it on us and it was really screwed up. We were all like really young – twenty-three, twenty-four, being chewed up by the system and paid nothing. I just kind of got obsessed with the idea of talent being churned out for schools, and just being chewed up by the machine of the corporate art music videos. They were just looking at the talent coming out saying ‘’let’s pay them nothing, and destroy them.’’

I CAN SEE YOU is a version of that. Guys in an advertising agency who are really young, who may be very good at what they do. They have a lot of energy, and they just get chewed up by the system. So we follow the main character who’s an artist, who doesn’t understand how that works. He may be on the edge already, and he just gets chewed up. He’s grist for the mill basically. So that’s where the idea for it came from. At the time Ti West (I’d grown up with Ti), he had done his first film THE ROOST for Larry Fessenden. So Larry financed THE ROOST, and after THE ROOST we both pitched him this really small fifty-thousand dollar project. Two different stories about three guys going around in the woods with weird shit happening. It was going to be like a grindhouse double feature type of thing. So his film was TRIGGER MAN and mine was I CAN SEE YOU. He loved the idea, but we all realized that they were both enough for full feature films, so we just split them up and made them on our own. So that is how it came about.

EB: I CAN SEE YOU is unique in the way that you have a vision/dream sequence toward the end, an almost camp like musical scene. The imagery at the ending of the film is especially unique. Where did this originate?

GR: I liked the idea that as reality was breaking down for the main character he began to see the people around him as aspects or elements of his own persona, and he would see things in people that he wanted to remove from them. He would see a caustic part of someone’s personality, and he would want to use that against himself. It’s actually an expression of that. In Chris Ford’s character he saw something in that guy that was cutting him apart, and he took that literally. So it was a literalization of that feeling in their relationship. There’s a lot of that expressive literalization towards the end of the film. I watched a lot of Jodorowsky, and Kenneth Anger. Semi-magical stylized, heightened expressionism. I wanted to explore that in these kind of weird torrid relationships. If you go out into the woods there’s only room for those things to grow. You don’t have the confines of the city. It’s suddenly expansive. I always like doing research. I don’t really do drugs, because I don’t like being out of control, I’m too neurotic. I do have limited experience with it, and I’ve been fascinated by it. So in looking into psychedelics, and where that even comes from I became obsessed with the origin of the word psychedelic, which basically means “mind manifest”. Those are the Latin roots. That’s how it was coined in the 50s. So I liked the idea of mind manifest. Things from the internal being manifested outside. Not necessarily as hallucinations, but as figurative expressions of the internal state. So my feeling was we’d go out into the woods with these characters and there’d be all these tensions, and unresolved issues between them they would literally contort, manifest out, and kind of suffocate everyone.

EB: At the point in the film when Ben is swimming with Summer Day. He does not have his glasses on. He has trouble being able to see her. Her image just becomes totally blurry, yet he is still trying to carry on a conversation with her. It’s embarrassing, and terrifying. Can you explain this scene?

GR: That’s the world I live in! I’m completely blind. The sunglasses I’m wearing are actually prescription! You are like a blur right now. I’ve been in situations like that where I’ll be swimming, at the beach, I talk to someone, and I can’t see them at all. It becomes this weird thing like I don’t know how to read you. It’s a really upsetting situation.

EB: It’s really upsetting watching him trying to keep up the conversation, and make the motions.

GR: It also mirrors this passionate moment they had together that was in the heat of the moment. They were by a campfire. They went off, and it meant a lot to him but it didn’t mean anything to her, because why should it? He’s just some guy, and they had a thing. The next day he’s realizing we have no connection, we have nothing here. So she just is kind of dissolving. That literalizes. She dissolves in the woods and disappears, and he misplaces that anger onto his friend. He believes his friend is responsible for it. Then comes the subjective reality for us in the film. That’s the turning point for me. When he realizes that his emotions have gotten the better of him.

EB: Ben is very easy to sympathize with, but he shouldn’t be. He’s very quiet, morose the whole time, dealing with his own inner turmoil. How did you develop his character?

GR: Yeah, he’s pretty mopey! Ben and I describe him as the worst aspects of both of our personalities. Ben Dickinson actually directed a movie called FIRST WINTER. Then recently directed CREATIVE CONTROL which is about augmented reality. After I saw it I was joking with him that it’s a sequel to I CAN SEE YOU, because it kind of is. He uses augmented reality. He recreates a woman he has a crush on in the augmented reality. He can’t really see the world around him the right way. It’s not literal, it’s a very figurative thing. He can’t interact with the world unless he’s doing it with the augmented reality. He kind of recedes into that, and he’s playing a similarly mopey ad executive character. He directed it, but he’s also playing the lead. It’s great. As a pairing with I CAN SEE YOU it’s fun. It’s all about glasses as well.

EB: What are some of your inspirations, what fuels your ideas most?

GR: I’ll rattle off a list. Philip K. Dick. Ubik by Philip K. Dick. Ubik is a big influence on I CAN SEE YOU. The spray is like Ubik spray in the book. Nicolas Roeg is a huge one. Editing wise the movie is kind of modeled after WALKABOUT in some ways. In the beginning of WALKABOUT everything is in the city, and everything is crazy, and chaotic. Just crashing together, and then you go out into the woods and it just expands, and becomes this textural experience. The structure is kind of based on that and the first ten minutes of PRINCE OF DARKNESS. Carpenter, David Lynch. I get a lot of shit for the red curtains thing in I CAN SEE YOU. It was supposed to be blue curtains. A powdered blue suit on blue curtains. We had that stage in my hometown where we shot. At the last minute they told us we can’t use smoke machines because they had a laser based fire detection system. We had to shoot it at my high school which only had red curtains, and then for years everyone was like oh yeah that’s like David Lynch. There are other things that I’m ripping off from David Lynch that I am fully willing to admit. The red curtains was not one of them. We actually tried at the time to take out the red curtains, and make them blue on computer, but it was just too much work. So Lynch, Roeg, Kenneth Anger, Jodorowsky, all those fellows. A lot of pulp science fiction writers.

EB: What is your newest project?

GR: I have a number of things in progress. I just finished writing a video game for PlayStation 4 with Larry Fessenden called UNTIL DAWN. It’s a super cinematic slasher film game. Very traditional in some sense like a slasher movie. Kids go up to a lodge in the woods. I wrote the dialogue with Larry. It’s a weird experience though. In this game all of the eight characters can die at different points. So writing the dialogue was like writing twenty-five different parallel universes with the same dialogue through the whole thing. Because chapter eight could be Ben and Ashley, or it could be Chris and Mike. Having similar conversations. A very fractured, layered way of writing. It was a really interesting project. It comes out next month.

I’m here at Fantasia’s Frontières market to pitch THE DESIGNER, which is a film I made about a video game designer. I wrote it a couple years ago after we finished a pass of the video game. I’ve been sitting on it. It’s been dormant for a while. So I resurrected it. I feel like it is pretty relevant now. It’s about augmented reality, and mundane usage of video games, tablets, interactive websites, even cars now. It’s about engaging. How you interact and touch something. I also have a couple other projects in the works.

EB: Tell us about your episode “The Caregiver” in Chiller’s FIVE STATES OF FEAR anthology film, and how it relates to themes that have been in your work previously. [Ed. note: The segment is about a vengeful wife charged with taking care of her unfaithful husband when he is paralyzed]

GR: That was a weird experience. I pitched a bunch of ideas I loved. They picked the one I liked the least. I liked the idea of someone who has locked-in syndrome. I liked the idea of a physical outer stillness beating to an inner vibration. I didn’t want it to just manifest like I’m gonna raise you into the air now and spin you around. That’s fun too, but for this I wanted it to be really shitty. Like the main character can only move a cup half an inch, and that’s his day. Then he takes a nap. That’s all he can do, and he’s just being tormented by this woman. We’re not sure at the end if he really does make her crash. He’s just locked in. I wanted to go more into his head at the end, but I was talked out of it. I wanted it to be very unclear. Originally, I wanted it to be that he dies then we go into a fantasy version at the end, and that’s where he gets his revenge. That would be his one moment of peace or accomplishment. Both the characters in that are horrible people. It was an interesting, fun TALES FROM THE CRYPT-type exercise.

EB: Can you talk about the sound design in your episode “The Grandfather” for Larry Fessenden’s radio play project TALES FROM BEYOND THE PALE? You use animal/cat sounds in a very particular way.

GR: I had a whole origin for that which I actually don’t remember right now, but part of it was that I wanted to do something with Angus Scrimm. He has an incredible voice. I was like I just want to have that voice in my head for half an hour. Just hear him talk, and muse about things.

My wife works with a lot of geriatric patients. She did research on Alzheimer’s disease for a long time. I mentioned the thing I’m most afraid of is my own brain turning on me. That’s what Alzheimer’s is. Only the tragic blessing is that you’re just gone basically. I was like what if a guy is somewhere between a threshold? He might be slipping away. He might be losing his sense of what things are. He might be becoming demented. Or he might not. What would that feel like from his perspective? I thought doing it from an audio perspective would give an interesting way to plant a lot of visual, and conceptual scenes in the viewers mind. To let it blossom in their heads. That is kind of the whole point of TALES. So I was like, let’s take someone who’s maybe going crazy, and have the sound of a cat meowing turn into this weird stretched-out voice.

EB: There’s many street cats where I live. At night, when they are fighting, or having sex it sounds demonic. Like a portal to a dimension could be opening.

GR: In L.A outside in the alley beside our house sometimes, I’ll wake up in the middle of the night, and me and my wife are like who is dying?! The sound morphs. Your brain does that thing. It can’t figure out what it is. We just have these patterns of recognition. If something does not fit into that recognition, it’s almost an acid trip feel. That euphoric feel of your brain stretching, contorting, and creating a new neuro-pathway to accommodate for it. It’s how I approach writing, and sound design. To make things that are familiar but slightly off. I was reading an interview with Aphex Twin when the album Syro was coming out. He did a whole interview where he talks about that. I was like I knew it! I was so excited that was his approach.

EB: What kind of music do you listen to? Anything experimental? Noise etc..?

GR: I listen to a lot of noise when I write. It puts you in an emotional space, and it doesn’t distract you. I use music a lot as a kind of utility based on everyday life. It helps me get into a space. It’s hard for me to write to things that take all of my attention. Noise can go both ways. I can listen and hear every detail of it, or I can put it on, and let it affect me subconsciously. I’ll hear it but I won’t be hearing it. I know it’s a good writing day when I don’t realize the record has been on for forty-five minutes.

EB: The sound in I CAN SEE YOU is very apparent. There are droning sounds, and vibrating that turn into human sounds. Human screaming also turns into mechanical sounds.

GR: I like the idea of that. Back to the psychedelic thing. The morphing contextualization that the brain does. I’m very fascinated by the way our brains work. It’s kind of an obsession. I just like the way our brains try to make things understandable, and fail all the time. It terrifies me. In the original director statement I did for I CAN SEE YOU I said that the thing I’m afraid of the most is my own brain failing on me. It does so much work filling in. If it’s missing information it fills it in. Often, it fills it in wrong. It creates these things that are not right. That is terrifying, because you realize you lose a connection to the world. It’s like Ben not seeing her in the water. Her face is blurry. Your brain is still trying to fill in a face. The way it blurs out the mouth and eyes. You see the most horrific representation of a face. It’s the same thing with sound. I don’t see sound any differently than I do visuals, so that sort of audio play from one place to another is the same idea. To me it’s just like a smearing of visuals. Blurring. The way I like to approach sound design is essentially a visual. It’s a visual medium, it’s just a different form. Like painting. You have a palette. You can put things together in a certain way. You can layer them a certain way. It’s a very similar language as the visual language. It’s just not visual. Like a synesthetic connection between visual and audio, that’s fairly easy to tap into. I think a lot of people just don’t give sound enough though in a movie. Which is a shame because it’s almost like black magic. You can really effect people in a way that they’re not consciously aware of, but they are very subconsciously aware of when it happens. Drone sounds, and things like that will kind of cut past all the intellectualism when you are watching something. You’ll just feel it.

Below: Photos from Fantasia’s presentation of TALES FROM BEYOND THE PALE: LIVE on Monday July 27, 2015. Photos by Julie Delisle.

August 15, 2015

August 15, 2015  No Comments

No Comments