DESIGNS ON DEATH

DESIGNS ON DEATH

The History of the Scandinavian Crime Thriller

By Paul Corupe

——————————-

A body left lying in the bottom of a drained river, a photo collage of suffocated female victims, a lockbox of severed hands or an unseen bloody finger hiding in a bowl amongst cheese doodles—these grotesque but indelible film images are poised to overtake delicious meatballs and affordable, unassembled furniture as the most visible Scandinavian exports. Brimming with brutality, chilly emotions and a heaping We use these more than any others and are happy with them. Cialis professional: our Online Canadian Pharmacy helps you find the real deals at mail-order and online pharmacies. serving of moral relativism, Scandinavian crime thrillers are booming again, picking apart a crime-ridden, corrupt region where the characters are often as remote and isolated as the windswept landscapes. While Sweden has dominated the trend for several decades, Denmark, Norway and (unofficial inductee) Iceland aren’t too far behind, helping to weave a regional network of novels, films and television that have helped defined these countries’ modern cultural output.

Though the steady stream of crime narratives pouring out of the area have occasionally seeped beyond the fjords to flirt with international popularity, the genre’s most recent wave has pushed its socially and politically tales of murder and drugs to an international audience. While some tales still adhere to the slow, analytical approach to unraveling mysteries favoured by Stieg Larsson in his breakthrough novel The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo to uncover underlying social ills, more recent film adaptations like Easy Money (2010), Headhunters (2011) and Black’s Game (2012) have instead focused on the very people navigating the Scandinavian underworld, where greed is fair game and corruption generic cialis professional runs rampant.

Scandinavia has a long line of crime fiction and filmmaking, with the printed word and the moving picture walk hand in hand, often feeding off real life atrocities as they depict. But it really started in Sweden in the 1960s and 70s, when authors Per Wahlöö and Maj Sjöwall collaborated veggie levitra on 10 detective novels following the character of Martin Beck, a downtrodden investigator with the Stockholm Homicide Squad. Beck’s paperback debut, 1965’s Roseanna, was the first to be adapted to in 1967, but Beck really broke through onto the screen in Stuart Rosenberg’s underrated Hollywood police procedural The Laughing Policeman (1973), with Walter Matthau playing the lead sleuth (only with a different name) on the trail of an assassin who gunned down nine passengers on a bus.

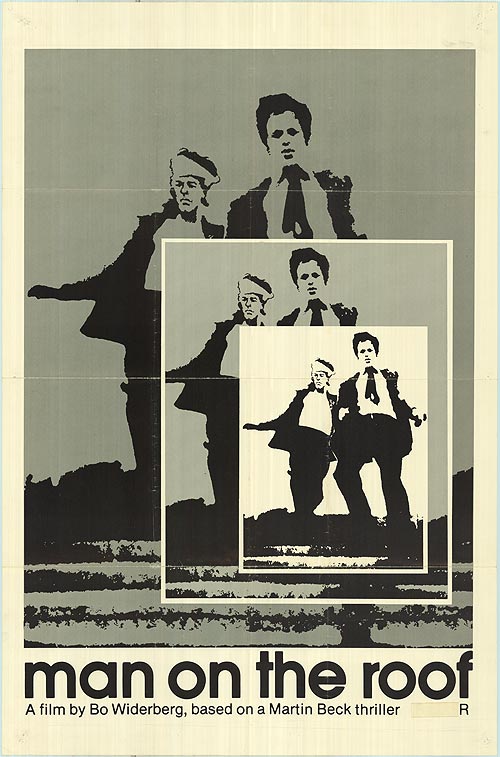

Not to be outdone, director Bo Widerberg brought Beck back to his Stockholm origins for 1976’s Man on the Roof, which still stands as one of Sweden’s most popular successes. A tense adaptation of Wahlöö and Sjöwall’s novel The Abominable Man, the story sees Beck’s investigation of a police officer’s murder lead him to a rooftop raid on a sniper targeting cops. Directly inspired by the international success of The French Connection (1971)—aside from the sniping sequences, Widerberg even offers his own foot chase through Stockholm’s subways—Man on the Roof suffers from a vision bigger than its budget, but it’s still a well-crafted thriller, featuring a surprisingly gory murder sequence and the same palpable paranoia that fuelled many Hollywood thrillers cialis online us of the same era. What the film lacks in Friedkin’s New York City grit it makes up for in unrelenting bleakness—from melancholy Swedish settings and Beck’s tending to the mundanities of everyday life, which is often interrupted by bursts of inhuman violence.

On the big screen, the already popular Beck struck an even bigger chord with hometown audiences and it isn’t too uncommon to see Man on the Roof celebrated alongside certifiable Swedish masterworks by Ingmar Bergman and Victor Sjöström. Although a few scattered Beck films followed, the character made a notable return in 1993 for a new series viagra to order of TV films based on the original novels. These episodes saw Beck portrayed by Gösta Ekman, who was n stranger to Swedish crime, having appeared throughout the 1980s as the leader of a band of small time criminals in the popular The Jönsson Gang films.

In 1997, having exhausted Wahlöö and Sjöwall’s books, a new generation of writers began penning mysteries for the new TV series Beck, this time with Peter Haber in the lead role. But by this time, Beck already had strong competition—in 1991, author Henning Mankell introduced readers to police detective Kurt Wallander, a character who may yet rival Beck in both longevity and impact on the genre. If Beck was a little dour then Wallander is downright gloomy, a gifted but increasingly troubled detective who seems to struggle just to get through the day. Wallander’s jump to the big screen was much faster than Beck’s, as he appeared in a nine-film series that began in 1994, with 26 telefilms following in 2005.

While grumpy gumshoes Beck and Wallander tower over Sweden’s crime film genre, Scandinavian crime films have begun to focus more on criminals rather than the cops. It’s been increasingly suggested that the most recent boom in Scandinavian crime novels, films and television series are due to the population’s heightened sense of failure over the cradle-to-grave social welfare programs, especially in Sweden. This theme is prominent in both the Beck and Wallander mysteries, as the protagonists frequently struggle against a world of broken promises riddled with corruption, classism and violent crime. However, this new breed of Scandinavian crime films strip down those police procedural narratives even further by removing the (mostly) impartial audience surrogate and delving right into the lives of those who have turned to crime—the victims of an increasingly corrupted social system.

Before his career-solidifying 2011 hit Drive, it was perhaps Nicolas Winding Refn who popularized the trend with his groundbreaking Pusher trilogy, a post-Tarantino crime series that drastically changed the stakes of these films. No longer were audiences riding along on a meticulously dissected murder case, but were instead dumped into the heart of the Denmark’s backalleys to follow antihero criminals who run afoul of powerful criminal organizations. The first Pusher film, released in 1996, stars Kim Bodnia as Frank, a drug dealer whose chance at a big score turns sour. Chased by the cops, he’s forced to scatter a large package of heroin into a lake to avoid a possession charge, putting him heavily into debt with Milo, a local drug lord. Frank gets increasingly frantic as the film goes on to raise the money—but every lead dries up and he knows that Milo’s enforcers will torture and kill him if he doesn’t pay up.

Besides two sequels, the film spawned a host of imitators, and Refn still keeps a severed finger or two in the crime film industry he helped foster, most recently as the executive producer of Black’s Game (2012). Based on the novel by Stefan Mani, this Icelandic crime thriller is the tale of a petty criminal who helps out an old friend and is suddenly recruited into the country’s most insurgent and dangerous drug organizations at the turn of the millennium. Director Oskar Thor Axelsson gives a taste for the variety, competitiveness and brutality of criminal activity in the country—bloody beatings, insurance scams, drugs, armed bank robberies all build on each other until the film’s final showdown, which is based on a true event, the largest drug bust in the Iceland’s history. It’s a story of the hunger of these criminals, as they easily manipulate the social systems and turn to crime for hedonistic thrills that eventually unravel and turn deadly. It has become one of the highest-earning Icelandic movie ever made, and for good reason—like Easy Money (2010), another soon-to-be-released Swedish crime film about a drug runner—it’s a slick and accessible crime story that owes much to the Western style crime movies of Scorsese and Tarantino, only with a distinct regional flavour.

Also slated for to make a big splash this year is Jackpot (2011), scripted by breakout Norwegian author Jo Nesbø from his own novel. Although Jackpot shares some of the same themes as Black’s Game, it’s more of a dark comedic take on the crime genre. It’s an approach the similar to the recent Norwegian Tomme Tønner series as well as the Danish bank robbery comedy In China They Eat Dogs (1999), but this strain of the genre can be probably traced further back to The Jönsson Gang and Norway’s own long-running The Olsen Gang comedy-crime series, which began in 1968. While Jackpot features a familiar police inspector character, it’s still largely told from the point of view of everyday working stiff Oscar (Kyrre Hellum) who, with a trio of ex-cons that work with him at Christmas tree factory, cashes in big time in a soccer betting pool. But when the characters start killing each other off for a bigger slice of the pie, Oscar must go to increasingly ludicrous attempts to collect the money, hide bodies and avoid the police.

An exceptionally bloody but still frequently funny film, Jackpot stands out from the sombre atmosphere of most of Scandinavian thrillers; the film’s most notable set -piece is a wild shoot-out in a sex shop, with XXX-rated DVDs and blow-up dolls flying through the air in a hail of bullets. But it still manages to broach many of the same themes—the (not-so)-rehabilitated criminals could be the eonforcers from Pusher 10 years later, at least one character uses his official position to take advantage of the situation, and Oscar’s near-poverty is almost enough to convince the police that he would kill anybody and everybody to become a millionaire. It’s a twisty and unpredictable tale from Nesbø, who has become one of the most popular crime authors in Larsson’s wake—the recent film Headhunters (2011) was also based on one of Nesbø’s books, and Martin Scorsese planning to direct an adaptation of The Snowman, an entry in Nesbø’s ongoing Oslo-set Harry Hole series about an alcoholic police officer.

But despite this increased attention on criminals, Harry Hole isn’t the only streetwise detective still stalking the streets of Scandinavia; the almost paralleled success of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and the other books in Larsson’s Millennium trilogy has seen to that. Published post-humously in 2005 and in North America in 2008, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo was first adapted for the screen in 2009 by Niels Arden Oplev. Generally, the book (and film adaptations) share Beck and Wallander’s approach to crime-solving, as journalist Mikael Blomkvist investigates the 30-year old disappearance of a girl with the help of Lisbeth Salander, the young titular hacker. However, the story does not simply allude to the social issues facing Sweden, but lays bare the corruption of social institutions and big business, even having Lisbeth literally raped by the system—her guardian forces her into sexual acts before he will allow her access to her bank accounts. Though not actually police officers, those characters fit in nicely with the newer generation of troubled sleuths—Swedish writer Helene Tursten’s medical expert Irene Huss, who leads an eccentric team of police investigators, Hakan Nesser’s grumpy divorcee Van Veeteren and Gunnar Staalesen’s former social worker Varg Veum are all fictional detectives that have made the jump from books to television.

But it’s interest from other countries that continue to put the Scandinavian crime trend over the top. Translated versions of books by popular authors such as Camilla Läckberg , Arnaldur Indridason and Karin Fossum are readily available across the globe, while the BBC recently cast Kenneth Branagh as Wallander in a new series based on the Swedish TV movies. In the United States, AMC is set to run their second season of The Killing, based on the Danish television series Forbrydelsen where every episode covers a 24-hour period in one case, and Fox is planning to remake Those Who Kill, a series based on the works of Danish novelist Elsebeth Etholm. And Hollywood’s biggest directors are just as smitten—aside from Scorsese, we’ve already seen David Fincher’s take on The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2011), and Christopher Nolan tackle Erik Skjoldbjærg’s Insomnia (1997), with new versions of Iceland entry City State (2011) and the aforementioned Easy Money in the works.

Even though this recent rash or remakes must be validating for Scandinavian authors and filmmakers, they’re also somewhat superfluous. Intrinsically tied to their settings, the original books, films and TV adaptations act as more direct and vital statements on the social situation of the Scandinavian countries. And even when the international interest begins to die down, these homegrown detectives, investigators and cops will still be there, just as morose as ever, paying tribute to Beck in their rumpled clothes and poor health habits while petty criminals desperately scurry under their feet, trying to raise the money they need to stay alive.

July 24, 2012

July 24, 2012  No Comments

No Comments