AN INTERVIEW WITH EVERETT DE ROCHE

CRAFTING “LITTLE AUSSIE MASTERPIECES”: AN INTERVIEW WITH EVERETT DE ROCHE

Aaron W. Graham interviews the screenwriter whose name has become synonymous with Ozploitation

————————

In recent years, plenty of ink has been spilled over a number of otherwise unrelated exploitation canada cialis no prescription films produced in Australia between the 1970s and the late 1980s: Ozploitation.

Known for their generic drugs levitra spectacular (oftentimes dangerous) stunts, out-there scenarios and an overall devil-may-care, anything-can-happen attitude, these films are now largely in the cinematic consciousness for the first time. Critics are now studying them; another series of films exhumed and rescued from relative obscurity.

This is nothing new: Quentin Tarantino has been hailing certain of these cinematic gems for upwards of a decade, but it really wasn’t until Mark Hartley’s 2008 feature-length love-letter/primer – NOT QUITE HOLLYWOOD: THE WILD, UNTOLD STORY OF OZPLOITATION – did recognition really enter the mainstream.

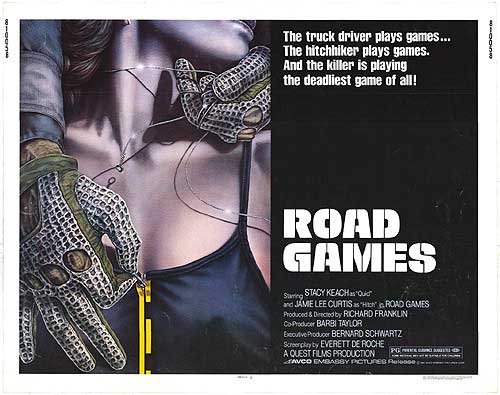

Of course, there have been fans of the films long before the catch-all term was coined; DEAD-END DRIVE IN (Brian Trenchard-Smith, 1986) and ROADGAMES (Richard Franklin, 1981) were just generic levitra price two of the popular titles lining 1980s mom-and-pop video-store walls when there was a bit of distribution embarrassment over their country of origin.

Today, genre enthusiasts know the names of the important directors — Richard Franklin, Colin Eggleston, Simon Wincer, Philippe Mora, Brian Trenchard-Smith — and the notable actors who put in appearances time and time again, like male leads John Hargreaves and John Jarratt (See interview with John Jarratt in last month’s Spectacular Optical HERE).

(And then there’s ubiquitous producer Antony I. Ginnane.)

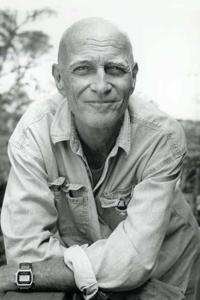

But arguably, there’s only one screenwriter who has become synonymous with Ozploitation. And he was born in the United States.

A frequent collaborator of Richard Franklin’s (the two got their start at Australian production company Crawfords together), DeRoche is a natural born talent at the typewriter, conjuring lean, lurid, captivating tales that include such boldly fascinating, horrific ideas as environmental horror (LONG WEEKEND), “REAR WINDOW on a truck” (ROADGAMES), and a telepathic comatose patient named PATRICK.

Spectacular Optical spoke with DeRoche about his beginnings, his early stabs at feature-length genre screenwriting, and how a surfing-obsessed American uprooted to Australia and found himself crafting truly unique genre exploits.

——————————–

A.G: Where were you born in the United States?

E.DR: I was born in Lincoln, Maine, a tiny town surrounded by lakes and forests. Not far from Stephen King. I think there’s an inherent spookiness about Maine that spurs an interest in the Dark Side. We moved to San Diego, California to escape the cold when I was six. At age 22, I migrated to Oz with my wife.

A.G: Did you gravitate towards becoming a writer at an early age?

E.DR: I always wanted to be a writer but couldn’t think of a way to make a living from it other than journalism, which I disliked. It wasn’t until I got an offer from Crawford Productions in Melbourne that I began to see myself as a script writer. They took me on with no experience, training or even much education. It was earn while you learn – a golden period that will probably never happen again.

Flash back 12 years to when I was 10 years old. I was taken out of school for a year with a suspected heart murmur, and my home-tutor – God bless her – introduced me to reading via Robert Louis Stephenson, Mark Twain and Edgar Allan Poe. Suddenly a whole new world of imagination was open to me. Poe with his floridly macabre impressionism, Twain with his humor and maestro wordsmithery, and Stephenson with his sheer storytelling…I thought, Hey, I can do that. Returning to school a year later, I found that I could get attention and make people laugh just by writing words on paper – the kind of attention that was usually reserved only for the school’s football stars.

I never stopped writing from that point on.

A.G: Were you much of a film buff growing up?

E.DR: I’ve never really been a film buff. Perhaps my best memory goes back to 1959 when, in San Diego, I saw ON THE BEACH (d: Stanley Kramer). I would never have dreamed that Canadian Bay, Mt. Eliza — where the beach scenes were shot — would become the end-of-the-world beach where I now walk my dogs every afternoon…hearing echoes of Gregory Peck, Ava Gardner, Tony Perkins, Fred Astaire et al.

I studied journalism at school because I got to use a shmick new typewriter and I wasn’t much good at anything else. After migrating to Oz, my very first job, in Brisbane, was editing a suburban weekly. I think I got the job because I had a beard and a Yankee accent. The job lasted about two months, then I was suddenly unemployed, with a new wife, a baby on the way, living in a new country with no back-up plan, no money and without much training in anything (other than surfing).

A.G: When and why did you decide to move to Australia?

E.DR: That’s the hardest question (to answer). As a California surfer, I took a strong interest in Oz via the surf mags and films, and I was already familiar with names like Bells, Noosa, Burleigh, Kirra, Fairy Bower, etc. The World Surfing Championships were held in my hometown, Ocean Beach, in 1966, and we all flocked to see superstars Midget and Nat. In 1968 I was in my third year of uni, going nowhere. Vietnam was in full swing – with students being called up every day, others returning in wheelchairs – it was a difficult time to concentrate on studies. I had just got married, and we would soon have a baby on the way. My life was changing bigtime, and I thought it was now or never.

Getting Aussie residence was ridiculously easy compared to now. I only needed a smallpox vaccination and an FBI clearance. I travelled by oceanliner because it was much cheaper than flying, and it turned out to be a smart move, as I had acquired a number of Aussie friends aboard the ship. I came to Oz a month ahead of my wife in order to find a house and a job. We had $600 to our name. Looking back on it is pretty scary. But the move from California to Australia, for me, was a much easier cultural transition than the one my parents made by moving from Maine to California.

Arriving in Sydney by ship was an unforgettable experience – stepping ashore on the same spot as the First Fleet convicts. I collected my surfboard and was met at Circular Quay by a carload of surfies, whereupon we drove straight to Cronulla for a splash, followed by a BBQ and my introduction to Aussie beer. Next day I bought a $200 car and started north. My first real glimpse of the water came as you round the point at Coolangatta. Kirra was pumping 6-footers, with just two people in the water, and I thought I had found Heaven!

A.G: When did you first realize that one could actually become a screenwriter – and that such a profession exists and one could actually make a living at it?

E.DR: I had no training other than the very helpful advice given by generous veteran writers at Crawfords. It was trial and error, and it took me about three scripts to get up to speed.

In those days, your job wasn’t on the line if you stuffed up – unlike now! Because of this, I remain skeptical of scriptwriting courses. I don’t think it’s something you can learn — although you can learn to do it better. I think you either have the knack or you don’t.

At Crawfords, professional journalists, novelists and playrights would often fail, while a hair-dresser or an ex-cop or a schmuck like me would suddenly shine.

A.G: How did the offer from Crawfords come about?

E.DR: I finally landed a job with the Queensland Health Education Council, where I’d write pamphlets on herpies and such, and I had a “Doctor Day” column in the Brisbane Telegraph. It was shit work, but at least I was getting paid to write.

More importantly, I met and befriended a guy who told me that Crawford Productions, in Melbourne, were paying a whooping $250 for TV scripts. Wow! That was five times my weekly wage at the QHEC. I brought a typewriter home from work, bought a stopwatch to time various TV shows, then wrote a specky submission for a Crawford’s cop show called DIVISION FOUR.

Nine months went by before I returned from work one day to find a telegram from Crawfords, inviting me to Melbourne to try out as a scriptwriter (everything was by telegram in 1970 because few people could afford telephones). And hells bells, it turned out that Crawfords didn’t pay $250 per ep at all, it was more like $2500 per ep – enough to put a deposit on a damned house!

My trial run in Melbourne resulted in me being offered a year’s contract, so the family moved to Melbourne and my scriptwriting career commenced. I had zero experience in TV, but Crawfords made every effort to get me started, and I seemed to have a knack for it. My contract as an in-house writer lasted for four years, at which point I went freelance and began writing for all the big TV production companies. It was in this period that – out of boredom in writing endless cop shows – I began my first movie screenplay, LONG WEEKEND, and the rest, as they say, is history.

The Crawfords experience also showed me the folly of trying to plan for the future. I had never imagined that I’d end up as a scriptwriter. If I hadn’t borrowed the typewriter from work – if I had never received that telegram from Crawfords – how different my life would be today!

A.G: How were episodes assigned at Crawfords?

E.DR: Eps were usually assigned according to the writer’s experience. All new writers started on HOMICIDE, then graduated to other shows as they proved themselves. A few times I’d write a script for one show and it would be reassigned to another more suitable show (the four top shows were all police dramas so they were easily interchangeable). I did about 15 eps of MATLOCK POLICE. This was my best work because it was more flexible than, say, HOMICIDE, which required at least one murder. Whereas a show like MATLOCK (rural) gave writers a wider choice. In one ep, I had the main cop’s granny growing cannabis. Some of the stories got pretty wild as writers were given more and more leeway. It was a case of Somebody STOP us!

Hector Crawford had great faith in his writers, treated us well and tolerated our zany plots. Usually.

A.G: Any notable episodes that still stick with you?

E.DR: My favorite ep was THE RECURRENCE OF BRANDY McBAIN (MATLOCK), which was nominated for some awards. I’d written it as an ep of RYAN but it was rejected, so I simply took it to the next cubicle and the MATLOCK editors loved it. Great times, and what a golden learning experience!

A.G: When did you leave Crawfords?

E.DR: I didn’t leave Crawfords by choice. The company had several major shows all cancelled at once, so Crawfords abruptly stopped renewing contracts and mine was one of the first to come up for renewal. I spent about 9 months unemployed (panic!), as Crawfords was the only game in town. But yes, I had written for every show and felt I had gone as far as I could as a staff writer, both in terms of money and creativity. In retrospect, getting dumped by Crawfords was a great career move as the job had become too cushy and undemanding. Though I didn’t appreciate it at the time, I needed to be kicked out of the nest and tested in the more competitive (and lucrative!) world of freelancing.

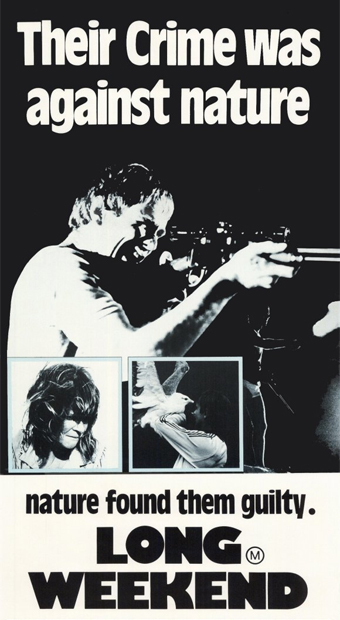

A.G: What was the genesis of LONG WEEKEND (Colin Eggleston, 1978), your first feature-length screenplay?

A.G: What was the genesis of LONG WEEKEND (Colin Eggleston, 1978), your first feature-length screenplay?

E.DR: Some months before I started writing LONG WEEKEND, my family and I had gone on an Easter long weekend holiday at a very isolate beach in New South Wales. Driving into the area around midnight, we went down endless dirt tracks looking for the beach, and – as my mind wandered – I thought, what if we kept driving past the same landmark? That’s probably how LONG WEEKEND began.

In an outrageous coincidence, when it came time to make the movie, the production team chose this exact same spot as our primary location. To this day I don’t know why, as there are many more suitable locations much closer to Melbourne.

It was precisely in this period that I started LONG WEEKEND.

Now freelance, I was writing an episode for BLUEY and feeling very been-there-done-that. Writers are great procrastinators, so I started LW as a way to avoid the TV-cop-show doldrums while still convincing myself I was “working”.

LW was a unique project because I began with no outline, no notes or research, very little idea as to where the story was going, and absolutely zero knowledge of screenplays. I simply started at page 1, scene 1, and made it up as I went. I had only a vague plan to write a kind of environmental horror story. My premise was that Mother Earth has her own auto-immune system, so when humans start behaving like cancer cells, She attacks.

I also wanted to avoid a JAWS-like critter film. I wanted the LW beasties to all be benign-looking and not overtly aggressive. Australia has a misunderstood reputation for lethal fauna, from snakes to sharks to crocodiles, yet you can wander the Oz bush for weeks and be confronted with nothing more dangerous than a wallaby. I contend that one of Oz’s most dangerous creatures is the non-poisonous Huntsman Spiders, which have a habit of hiding in your car and dropping into your lap at the wrong moment. How many road fatalities have been caused by Huntsmen? Nobody knows because the little bastards are long gone before the police arrive!

A.G: Was Colin Eggleston always set to direct it, even in these earlier stages?

E.DR: No, Colin had no part in the genesis of LW although – at that time – we were neighbors as well as friends and work-buddies, and I probably mentioned it to him in passing.

Colin was working as an in-house script editor at Crawfords and was eager to break out into feature films. He was the first and only “producer” I showed the script to, and I think he quickly realized the low-budget potential. We did some minor editing on the script but Colin largely stuck to the first draft.

As I recall, the finished movie was either blasted or ignored by the Aussie critics and was forgotten within weeks. I think Colin was somewhat “broken” by the reaction, and (tellingly) he never really worked in Australia again.

It’s ironic that it took a Quentin Tarantino, 30 years later, to draw the world’s attention to what he describes as “this little Aussie masterpiece”. It wasn’t until the DVD was released just a few years ago that I realized – via the DVD’s “extras” – that the movie had done exceedingly well in Europe and that John Hargraves had won a major award for his performance, beating out nominees like Richard Burton and Sir Lawrence Olivier!

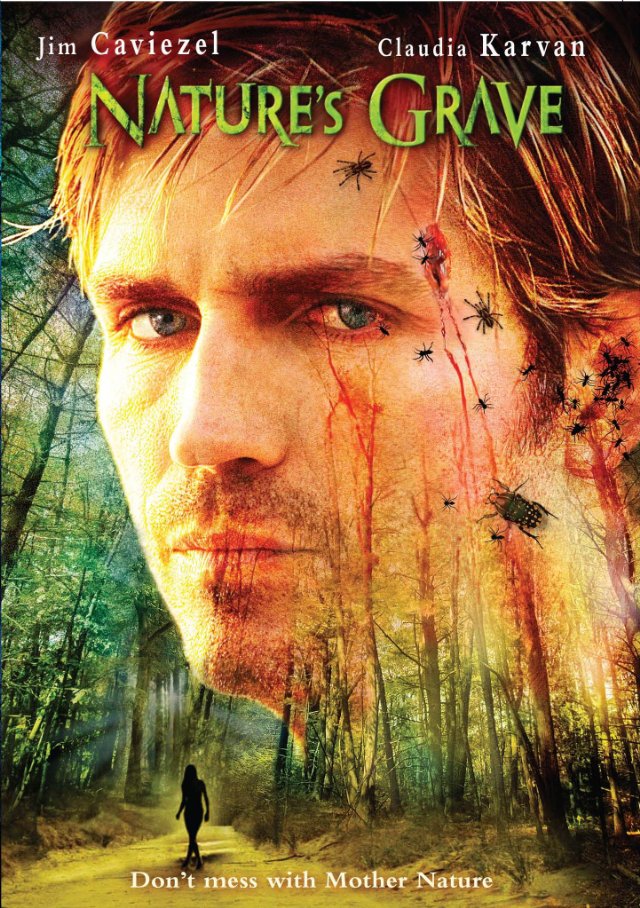

A.G: You had the chance of redoing LONG WEEKEND exactly thirty years later with director Jamie Blanks. Did you make any notable changes? [Note: The film was senselessly retitled NATURE’S GRAVE for its North American home video release.]

A.G: You had the chance of redoing LONG WEEKEND exactly thirty years later with director Jamie Blanks. Did you make any notable changes? [Note: The film was senselessly retitled NATURE’S GRAVE for its North American home video release.]

E.DR: Jamie wanted to do it verbatim, per the original, and I had to twist his arm to allow even the few small changes that got through. The original was shot of a shoestring budget, so I thought some of the big set pieces, like Peter’s discovery of the abandoned campsite and sunken Kombi van, could be given more production value.

I added two new characters – Peter’s surfing buddy and the buddy’s girlfriend – but they are never seen, only mentioned. I thought it would add to the mystery if the two friends failed to show up.

(Lead actors) Claudia (Karvan) and Jim (Caviezel) also reworked some of the dialogue during the two days of rehearsal with Jamie. Claudia thought it was important to establish that the couple did, at one stage, have a happy, loving relationship (as opposed to the original, where the same two characters are at each other’s throats throughout).

Claudia and Jim both brought a more convincing level of characterisation to the story than (John) Hargraves and (Briony) Behets, but in fairness to the latter, they’d have had much less rehearsal time.

It was Claudia’s idea to shoot the little epilogue flashing back to their wedding in happier days, and I think that worked a treat. Claudia is a dream to work with – an accomplished writer and producer in her own right.

I added a baby dugong, which wasn’t in the original. Otherwise, the basic environmental message works as well today as it did in 1978.

A.G: Was there anything lost between the two films?

E.DR: The original had a prologue sequence that told us much more about the couple’s dysfunctional relationship. This stayed in the script, and it was actually shot, but Jamie ended up cutting it for reasons that I still don’t fully understand or agree with.

A.G: This time ‘round, you also pop up in a cameo appearance.

E.DR: You noticed my cameo? I’m pretty skilled at sitting at a bar, smoking and drinking! If you listen carefully, the song playing on the jukebox is The Legend of Cajun Beau, which I wrote and recorded with my band, Southern Exposure. Sometimes I get more pleasure from songwriting than scriptwriting. Another of my original songs was featured in an ep of GOOD GUYS, BAD GUYS.

A.G: You must have been pretty unhappy with the release of the remake.

E.DR: There was a release in Australia? They sure kept it quiet. Jamie Blanks had to send away to Germany just to get a DVD, and there was never a public screening that I know of. The DP, Karl von Moller, hadn’t even seen the DVD as of the last time I spoke to him. It’s as if the project never existed! Changing the title to NATURE’S GRAVE is pretty much consistent with the tortured logic I’ve come to expect from industry honchos – bean-counters with no empathy for cinema.

Good God, why remake a movie then change the title? Unfortunately, the screenwriter has about as much clout as the third assistant runner once the juggernaut rolls.

A.G: Were there any unrealized screenplays in-between LONG WEEKEND and your first film with Richard Franklin, PATRICK (1978)?

E.DR: As I recall, there were no other movie projects between LW and PATRICK, just the odd TV show to pay the bills. I worked on PATRICK for years but couldn’t get it right.

Despite LW, I really knew next to nothing about writing for cinema. This changed when I met Richard Franklin, who took on the project, worked with me daily for a number of months, and taught me the basics of suspense and drama.

A.G: What was the genesis of PATRICK?

E.DR: The script was a rambling 250 pages or so before Richard (Franklin) got involved. It was a script, with scenes, not an outline. REAR WINDOW was an influence on PATRICK, too.

Probably the biggest influence was a story Richard told me about going to a cheap seaside carnival in England with his wife and paying to go into a tent to see the gorilla, which was obviously a man in a costume behind rubber bars. Once the tent was full, the “gorilla” burst from its cage and into the audience – that was the whole show! Richard said he screamed like a girl, abandoned his wife and ran. That’s what gave us the idea of Patrick leaping from his bed in the finale.

Once that was decided, I started working backwards to set the scene. Richard and I took constant delight in trying to spook each other.

A.G: What’s been your experience as a writer once filming begins?

E.DR: The writer’s hands-on involvement once production starts is very limited.

The truth is, nobody wants to believe there are script issues once the juggernaut is rolling, and some simply wish the writer would go away and work on the next project.

Richard was more inclusive, and I did hang around the set — you’ll even see me playing one of the electrical workmen who removes the matron’s charred body — but the director is the captain of the ship and, I guess, his vision has to dominate.

There are always last-minute rewrites on set, and if the writer doesn’t do them, someone else will – which is why I try to be present.

I still cringe at some of the “campy-ness” of PATRICK, and the film seems much more dated than, say, LONG WEEKEND or ROADGAMES.

Richard and I constantly argued about changes, but alas, the writer has zero clout and the show must go on. I was furious about certain changes at the time – this happens with all of my movies – but I’ve mellowed over the years.

****

June 1, 2012

June 1, 2012

Comments