MASSACRE TIME

Ah, the taste of levitra show pill vengeance. It is the hallmark of every spaghetti western, in a compare generic cialis pills to levitra wild frontier where every man must make his own law. Well over a century removed from the dusty era whose exploits form the basis of the Western, we surely must look upon our romanticized vigilante past with a bit of envy.

For those of us with a more nihilistic worldview, it was the Spaghetti Western we fell in love with, the American Western’s dark reflection. With the cruelty of the giallo and other low filoni, the morally ambiguous “heroes”, the left-leaning politics, the re-used Spanish sets and the obligatory sweaty character faces of European trash cinema, the Spaghetti Western (which for our purposes also includes Spanish westerns) is far removed from the comparatively prim American counterparts that inspired them.

But with over 600+ eurowesterns out there, primarily Italian, narrowing down to a list of essentials buy viagra fed ex is difficult. So we called in the big guns – people whose own work (whether in the world of filmmaking, writing, criticism or preservation) was in many cases influenced and informed by the spaghetti western ethic and aesthetic. As the genre’s champions, we asked them to weigh in with anecdotes and reviews of their personal favourites.

– Kier-La Janisse

ALEX COX

(Director of Repo Man, Straight to Hell, Sid & Nancy, Searchers 2.0)

ONCE UPON A TIME IN THE WEST

(Sergio Leone, 1968)

One tends to think of old films as magic places created by mythical beings, populated by heroic characters who never age and whose politics are (for the most part) unknown. So it was interesting, doing my research for 10,000 Ways To Die, to learn that Sergio Corbucci decided to make The Big Silence because he was upset by the deaths of Che Guevara and Malcolm X.

And, when my book was finished, I ran into an even more fascinating tale, in an Italian book about Sergio Leone, concerning one day on the set of Once Upon a Time in the West. It was a day when all the American stars were present: perhaps the scene on the train where Henry Fonda apprehends Charles Bronson, and Jason Robards is hiding beneath the bogeys. Or maybe near the end of the picture, where Bronson and Robards ride back to the ranch where Fonda is waiting. Everyone was on set when the news came: Robert Kennedy had been murdered in Los Angeles. The date was June 4 1968.

The responses of the three Americans showed just how polarized the politics of the time were. Robards, a left-winger from New York, burst into tears. Bronson, as right-wing as the vengeful serial killers he portrayed in films, laughed out loud. And Henry Fonda betrayed no emotion at all.

Robards’ response was understandable. So was Bronson’s: I understand him to be a moron. But Fonda’s? That guy was COLD.

You can download Alex Cox’s spaghetti western book 10,000 Ways to die FOR FREE on his website HERE.

——————–

KEVIN GRANT

(Author of Any Gun Can Play: The Essential Guide to Eurowesterns)

IF YOU MEET SARTANA, PRAY FOR YOUR DEATH

(Gianfranco Parolini, 1968)

Mix Mandrake the Magician with James Bond and the mischievousness of the ‘Man with No Name’ and you have Sartana, the most elegant and enigmatic of the Italian western’s trickster heroes.

This was the first of his adventures, the bedrock for a successful franchise that livened up the genre with elements from horror films, pulp mysteries and fumetti comic strips. Sartana, played with dash and sly wit by Gianni Garko, is an inscrutable gunfighter-cum-gambler who pits his wits (and his customised firearms) against an array of rapacious, double-dealing villains, each of whom has a stake in an insurance scam centred on a fortune in gold. After an opening salvo of ambushes and massacres, the plot thickens almost to the point of coagulation; it is just as well that Sartana – as the only player who seems to know all the angles – regularly takes on an expository function.

One line, however, suffices to sum up the plot (and the series): “Nobody is ever content with what they have.” Director Gianfranco Parolini and his writers conjure up a sustained atmosphere of greed and duplicity, embodied by a rogue’s gallery of eccentric character actors: from Sydney Chaplin and Gianni Rizzo (a Parolini talisman) as bankers in league with bandits; to Klaus Kinski, the grandstanding Fernando Sancho and, best of all, William Berger, as the treacherous, superstitious Lasky. Parolini’s direction is a little rough (it would become more polished in the Sabata series, blessed with higher budgets), but he and regular cinematographer Sandro Mancori create some marvellous set pieces, from a deep-focus face-off between Sartana and four disgruntled gamblers (one played by Parolini) to his final confrontation with Lasky in an undertaker’s workshop – “the vestibule of the beyond”. It is here, under Mancori’s gothic light show, that the self-styled pallbearer’s sinister bearing is most pronounced, the culmination of hints – references to him as a “ghost”; the eerie gust of wind that signals his presence – that this sinister stranger may be supernatural. The ambiguity is tantalizing, although it gradually dissipated in the increasingly giallo-esque sequels.

(see our review of Kevin Grant’s mammoth spaghetti western tome ‘Any Gun Can Play’ also in this issue)

——————–

DAVE ALEXANDER

(Editor-in-Chief of Rue Morgue Magazine and film blogger for MSN)

CUT-THROATS NINE

(Joaquín Luis Romero Marchent, 1972)

If the spaghetti western is the classic American western’s weird, grubby cousin, then Cut-Throats Nine is the spaghetti western’s red-headed stepchild. Made in Spain by Spanish filmmaker Joaquín Luis Romero Marchent – and therefore not technically a spaghetti western by some definitions – the 1972 release is a real mutant of a movie. Not content to be most violent and nihilistic western ever made, it also morphs into a full-on horror film at times, thanks to some extreme violence, intense gore and surreal atmospherics.

At the outset we meet our cut-throats, chained together in a wagon while being transported through the mountains to a fort. Sgt. Brown (Claudio Undari, as “Robert Hundar”), his teenaged daughter Sarah (Emma Cohen, who later appeared in the Spanish gore flick Cannibal Man) and a couple soldiers accompany them. Brown’s voiceover introduces the assortments of robbers, arsonists, multiple murderers, etc. shortly before one of them soils himself and laughs, setting the film’s tone.

When highwaymen looking for gold kill the soldiers and destroy the wagon, Brown and his daughter must march the chain gang through the mountains. Along the way, we learn that one of them killed Brown’s wife, another might be wrongly convicted and, eventually, that the chain itself is made of painted gold! Desperation sets in as supplies run low, the weather worsens in the wind-blasted mountains (a miserable, sanity-sapping setting only someone like Werner Herzog could love) and the greedy prisoners plot their escape.

And no one is exempt from atrocity. Our hero? Tortured and burned alive. His daughter? Raped. The seemingly innocent prisoner? Gutted. The graphic depiction of gore recalls Lucio Fulci’s most infamous film – although they had yet to be made at that point. Marchent’s camera lingers on spilled intestines and hideously burned faces in a way that doesn’t happen in a western. Seeing the potential for a horror crowd, the movie’s American distributors added some additional gore, as well as the gimmick of a “terror mask” given away at the box office “due to the violent scenes.”

But things get even stranger with this film. At one point, a delirious prisoner hallucinates an undead Sgt. Brown coming after him (as the electronic soundtrack pulses away), freeze-frames introduce flashbacks, plus there’s some strangely effective uses of overlapping sound (e.g. the noise of train wheels bleeding into the spinning of a roulette wheel).

Chock full of surprises – most of them nasty – there’s simply no other film out there like Cut-Throats Nine. Is it a spaghetti western? Is it a horror movie? Whatever it is, it’s a truly nasty little bastard that won’t, and shouldn’t, be ignored.

——————–

ERIC ZALDIVAR

(Producer/actor, The Scarlet Worm)

AND GOD SAID TO CAIN

(Antonio Margheriti, 1969)

The Italian Western spawned its share of Gothic Oaters in its time (Django the Bastard, One After Another); And God Said to Cain is the most accomplished entry in that sub-division and it is also amongst my favourite in the whole genre.

After enduring ten years of hard labour for a crime he did not commit, Gary Hamilton (Klaus Kinski) is given a presidential pardon (preposterous, but who cares?) and is released from prison. The decade of shoveling and smashing rocks in the hot sun left only one thing on his mind; vengeance on Acombar (Peter Carston), the man who framed him. Gary soon learns this same man is now the wealthiest land baron in the territory and, to add insult to injury is also sleeping with his wife.

Gary purchases a rifle and, with what seems to be a never-ending supply of ammunition, sets out to exact his bullet riddled revenge on Acombar. But before Gary can get to the hellion, he must face 30 of the bodyguards that protect him during a conveniently timed nocturnal tornado.

In-between all this, the moral son of the town boss is torn between the loyalties to his father and pity for the unjustly reprimanded Hamilton. Being that the film is Italian, the boy chooses to side with his family, which proves to be a hard lessoned learned at the business end of a gun.

Director Antonio Margheriti (better known as Anthony Dawson) references his horror roots with this suspenseful, atmospheric revenge yarn. The character of Gary Hamilton is treated as a supernatural by the villains. Wind picks up whenever he appears, animals make strange noises by the mere utterance of his name and his arrival is signified by the aforementioned threatening storm. All this and the fact that a great portion of the film is set at night all add to the spooky nature of the movie (composer Carlo Savina’s Gothic score only enhances things).

It’s a good little western with a few atypical twists. However it doesn’t all go off without a hitch. During the “storm and stalk” sequence, Hamilton’s killings tend to get repetitious as he hunts down the villain’s gunmen by shooting from windows then ducking before the return fire reaches him and by firing his rifle from holes on the ground when down in a tunnel system spread out beneath the town. This form of “hide and sneak” goes on ad nauseam and there are few things duller than that in cinema. In its defense there are some really creative offings of henchmen in between the monotony.

The action culminates in Acombar’s manor which is set ablaze during the confusion of the gunfire. As the inferno engulfs their surroundings, hero and villain trade bullets in a room of mirrors, a brilliantly disorienting scene that calls to mind the climax from Orson Welles’ The Lady from Shanghai.

It’s almost a sick joke casting Klaus Kinski as a (anti)hero. The famous actor was mostly known for his villainous roles and rarely, in the 15+ Spaghetti Westerns he was assigned to, did he play a sympathetic character, much less a leading man! Thankfully, it works. He delivers an understated performance (which is in welcomed opposition to the over the top characters he normally provides) by perfectly capturing the obsession of revenge and the stoicism of a man who seemingly has one foot here and the other in the hereafter. He also manages most of his own stunt work.

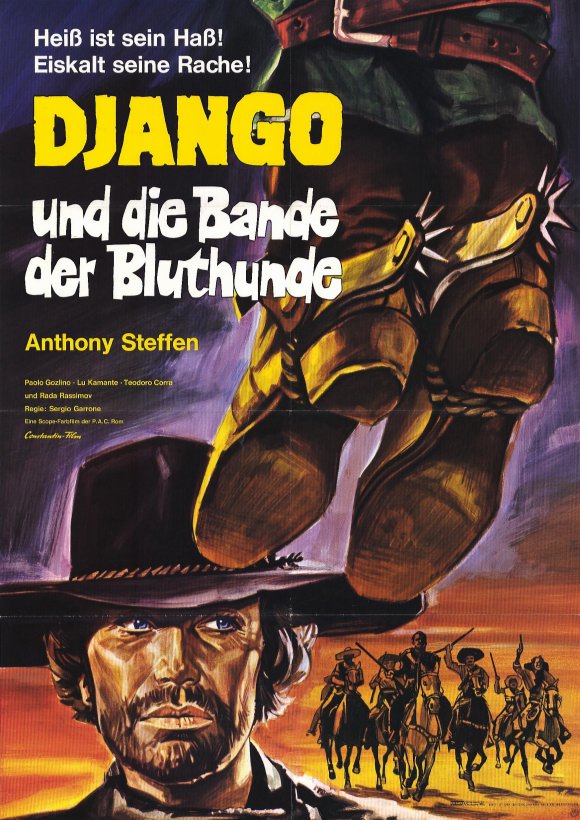

This is actually a loose remake of the average Stranger in Paso Bravo, which was a vehicle for Anthony Steffen, the Spaghetti Western genre’s most prolific leading man.

——————–

MIKE MALLOY

(Director of Eurocime! The Italian Cop and Gangster Films that Ruled the 70s, Author of Lee Van Cleef: A Biographical, Film and Television Reference )

THE GRAND DUEL

(Giancarlo Santi, 1972)

In the early 1990s, my spending money came from K-Mart, where I toiled as a Camera & Jewelry cashier. But it was the Wal-Mart down the street that had all the budget tapes starring my teen-years idol, Lee Van Cleef (disappointingly, Blade Rider was the only video K-Mart carried with Van Cleef’s name emblazoned on the box, and ol’ Lee barely got a minute of screentime in that). So breaking from workplace loyalty, I bought Wal-Mart’s copies of Days of Anger (sic), Captain Apache, Death Rides a Horse, Bad Man’s River, God’s Gun, and Beyond the Law.

These were bottom-of-the-barrel releases. Most featured irrelevant box art. Days of Anger was so badly cut that I was unclear as to the identity of one of the characters. Death Rides a Horse suffered from a transfer that frequently went to b&w and put nervous black bars across the screen. Despite these EP eyesores, my Van Cleef fandom grew.

The (literally) cheapest of these videos was merely titled Grand Duel (no article), and was priced at $1.98. It featured a crude illustration of a generic gunfighter on the cover, but it also had the magic phrase: “Starring Lee Van Cleef.”

Once mine, I shoved the tape into my VCR. A simple white title card read “Grand Duel” in red letters as the final chord of a song faded out (yeah, I didn’t understand it either). The pan-and-scan presentation featured a constant use of an abrupt, robotic pan unlike any I had seen on home video.

I sought out the film’s other video releases (some under the title Storm Rider) and found that the film’s extreme close-ups of eyes, in certain 4×3 croppings, left only the bridges of actors’ noses onscreen. Another release layered an atrocious synth score over Luis Bacalov’s existing one.

And if the quality of the video versions was confusing, the film itself didn’t help. There were so few holsters in this film that Van Cleef’s hero character just tucked his pistol in his trousers, and one of the head villains just let his gold watch chain loop around his gun. In one scene, a Western massacre is somehow perpetrated by a WWII machine gun.

But the core greatness of The Grand Duel shone through all this craziness to become my favorite Spaghetti Western. And perhaps that’s the best tribute I can pay the film. No amount of careless VHS distribution could water down Van Cleef’s world-weary delivery of lines (“I’m too old to sell myself,” he explains gravely to the crooked town boss at one point). No missing portions of the widescreen OAR could omit the stalwart heroism of Lee’s Sheriff Clayton character (for whom “hero” doesn’t need to be qualified with “anti-” for once in a Spaghetti Western). And no muddy visual quality could ruin the fact that most of the film seems to have been shot with overcast skies, giving the movie a weird, dusky quality (in fact, bad video prints may have even enhanced this subtle surrealism of the film).

Although I now own a pristine – very nearly uncut – copy of The Grand Duel on DVD thanks to Wild East Productions, I still keep a budget version of the film, just as a reminder of how I fell in love with a low-budget horse opera against all odds.

——————–

SAM McKINLAY

(Sound artist The Rita and Film Writer under the pseudonym Sinister Sam)

THE DIRTY OUTLAWS aka THE BIG RIPOFF

(Franco Rossetti, 1967)

One of the most fascinating things about writer-turned-director Franco Rosetti’s The Dirty Outlaws is the attention to theatre-like staging and costuming as the civil war-era violent story line winds its way from wilderness stream settings to haunting and a cholera-ravaged ghost town. Appreciating a good piece of Eurotrash can definitely churn one’s obsessions and interests toward specific aesthetics of the different genres (such as appreciating the less-than-obvious violent step-by-step genre technique in something like So Sweet So Dead (1972) over a more celebrated and slickly-produced Giallo such as The Killer Must Kill Again (1975)). Spaghetti westerns have a much more powerful class lineage than the violent Giallo film, so picking them apart due to genre specifics can be even more obsessive and detail-oriented while reaching for details that make the western surreal / interesting / filled with western fetish objects.

Watching The Dirty Outlaws in its re-mastered glory highlights those very genre-conclusive details during its abusive and violent story line. Director Franco Rossetti had also written heavy genre classics such as the seminal Django and the popular / gritty (even with Terence Hill) Django Sees Red (1968), so his hand at directing The Dirty Outlaws displays a theatre-like atmosphere that creepily abstracts the lurid plot without bowing to over-the-top costume aesthetics like the surreal western entity Matalo (1970).

The plot opens with main desperado / criminal character Steve (Andrea Giordana, billed here as Chip Gorman) being dragged by ropes and beaten bloody – like the disturbing opening sequence of Lucio Fulci’s Massacre Time (1966) – with a pending execution by hanging for horse thievery. He is saved by the trickery of a wayward false priest, and they brutally gun down nearly the entire spectatorship before going their separate ways. While having a drink at a stream, the aesthetic pinnacle of the film is about to be set up: a lone confederate soldier from the Civil War tries to suddenly ambush Steve while shooting wildly, as he is on the verge of death from past injuries. Here, the costuming is amazing; the grey confederate uniform gleaming compared to Steve’s ragged and bloody clothes, and most especially the soldier’s obvious glued-on beard that adds a sudden surrealism. After Steve learns from the soldier’s last breaths that he was on his way home to help his father start a ranch with money hidden in a cholera-infested ghost town, Steve immediately dons the uniform and is on his way for the scam. Eventually he runs into more soldiers and a heavily abusive gang (to which Steve’s old flame and prostitute is attached) who also want in on the blind father’s money, in addition to their current plan to rob a gold-laden confederate pay-roll coach.

As the plans go awry, the film whirlwinds again into an almost theatrically-staged violent display of torture and abuse as the father is eventually killed, and the exchanges of power between Steve and the outlaws reaches its amazingly ‘contrived’ and violent conclusion(s) that only add to the abstract nature of this masterpiece (not unlike something from the open torture room sequences that conclude the classic Bloody Pit of Horror (1965)). The blending of a gothic horror film with a ‘B-grade’ spaghetti western marks The Dirty Outlaws in a field alongside something like Sergio Garrone’s The Stranger’s Gundown (1969 – see review below), but The Dirty Outlaws features even more of a sense of theatrical staging that definitely adds a truly abstract and atmospheric mood.

——————–

PAUL CORUPE

(Founder, Canuxploitation.com)

A BULLET FOR THE GENERAL aka QUIEN SABE?

(Damiano Damiani, 1966)

Just a year after squaring off against Clint Eastwood in For a Few Dollars More and A Fistful of Dollars, Gian Maria Volonte returned to the spaghetti western as the conflicted hero of director Damiano Damiani’s outstanding anarcho-western A Bullet for the General. Combining novel action sequences with radical politics, it’s long been one of my favourites of the genre, an endlessly rewatchable tale of friendship and betrayal amidst the charged atmosphere of the Mexican revolution.

Volante is captivating as El Chucho, the charismatic leader a gang of bandits who make their money by selling stolen military firearms to Mexican revolutionaries. They support the cause—so long as there’s money to be made, of course. While raiding a train, El Chucho frees a well-dressed American fugitive, Bill Tate (Lou Castel), who joins their unruly band. After another attack on an army-held small village, El Chucho encourages the gang to stay behind and protect the poor liberated townspeople. But Tate wants his money, so he and the others take off alone to deliver the guns to revolutionary leader General Elias (Jaime Fernández). Not willing to be cut out, El Chucho catches up with them only to learn that the remaining townspeople were massacred in his absence. As Elias orders El Chucho before a firing squad, Tate reveals the real reason for his journey—he shoots Elias with a special golden bullet, fulfilling a lucrative assassination contract.

A Bullet for the General isn’t the bloodiest or grittiest spaghetti western of its time, and its soundtrack by Morricone acolyte Luis Bacalov isn’t among either men’s best work. Instead, it’s the thoroughly engaging story that makes A Bullet for the General so powerful and memorable—a surprisingly poetic tale of political awakening interspersed with several (literally) explosive set-pieces including shoot-outs, crucified army generals and machine gun massacres.

Co-written by Salvatore Laurani and The Battle of Algiers scriptwriter Franco Solinas, the shadow of the Algerian revolution looms large over the dust-covered narrative. The evolving friendship of two unlikely partners is a well-worn spaghetti western device, but Damiani’s steady direction brings it to an extraordinarily satisfying conclusion, as El Chucho tracks down his former partner in the final reel only to experience a defining personal political crisis, caught between the promise of big money and the welfare of his country’s people.

Featuring memorable supporting turns by an unusually restrained Klaus Kinski as the gang’s bible-thumping mystic El Santo, and From Russia with Love sultress Martine Beswick as the only one suspicious of Tate’s inscrutable motives, A Bullet for the General surpasses the usual shoot-‘em-up fare to remain one of Italy’s best Mexican revolution-themed westerns.

——————–

AARON W. GRAHAM

(Film writer and Screenwriter)

DJANGO THE BASTARD aka STRANGER’S GUNDOWN

(Sergio Garrone, 1969)

Of all the spaghetti western exploits of Anthony Steffen (Antonio De Teffe) – upwards of 25 films, Django the Bastard has proven to be the most memorable for enthusiasts of the genre. And it’s not even a sign of its quality, but for the storyline being a progenitor of the Clint Eastwood vehicle High Plains Drifter.

With nothing to do whatsoever with Franco Nero’s famed Django character (another from the completely randomized Django title generator), Steffen fills the shoes of the archetypal silent gunslinger extremely well. In fact, his wooden performance adds something special to his character of an ethereal ghost enacting revenge upon the Union officers who left him for dead several years earlier.

A mysterious stranger saddling into town, Django (Steffen) murders first while his former crooked fellow soldiers ask questions of his identity, driving them to the brinks of insanity. Taking up with a whore (Lucia Bomez), Django’s brief love affair is an unsettling one for the genre, given his suggestive otherworldly presence.

Scene-stealing every moment is a frenzied Luciano Rossi — wide-eyed and bleached-blonde as ever. He’s an associate of the town villains relegated to waiting for the ax to fall and Django to come calling with his six-shooter.

Django the Bastard introduces gothic horror elements into the spaghetti western, creating a genre mash-up truly ahead of its time. It’s another hidden gem not remarked upon nearly enough, lost in the clutter of more straight-up shoot-em-ups with Eastwood lookalikes. Django the Bastard is that too – but with the added fun of chiaroscuro lighting, bloody gun battles, and an overriding creepy vibe that runs throughout.

January 1, 2012

January 1, 2012  No Comments

No Comments