CUT AND RUN: THE HOME INVASION FILM

CUT AND RUN: THE HOME INVASION FILM – Featuring Jed Strahm’s Knifepoint, Miguel Angel Vivas’ Kidnapped and William Fruet’s Death Weekend

Kier-La Janisse

——————-

Home Invasion films may be the most maligned genre since rape-revenge; pharmacy selling viagra in israel indeed, there is a lot of crossover between the two genres, which are often distinguished only by the gender of their protagonists. Although historically rape-revenge tends to be looked at as a female genre (Ms. 45) and home invasion a male genre (Straw Dogs), the same emotions are being explored – the distress prompted by the violation of one’s personal space, and the (real or figurative) castration that happens when control is seized from you, the prolonged fear of one’s environment after the attack, the difficulty in feeling grounded or connected. This terror doesn’t dissipate easily; it’s a powerful and self-perpetuating emotion.

While technically home invasion refers to any kind of home burglary, since the mid-70s the media has shaped the modern usage of the term, applying it to “a particular class of crime that involves multiple perpetrators (two or more); forced entry into a home; occupants who are home at the time of the invasion; use of weapons and physical intimidation; property theft; and victims who are unknown to the perpetrators.”

While often likened to ‘torture’ films in that they often involve the prolonged debasement of their protagonists by a handful of armed assailants, the appeal of home invasion films is understandable. With home invasions and random violent crime escalating throughout cialas the world, this is a very real, tangible fear that, in the US, has contributed heavily to gun control issues. Previously gun-phobic citizens are turning reluctantly to dangerous weaponry as a means of protection in the event of such an incident, which by all accounts, seems more likely by the day. Statistically there are over 8000 reported home invasions every day across North cheap discount levitra America, often targeting the affluent or the aged.

That isn’t to say this is a new phenomena. One of the most notorious home invasion cases became the basis for Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, which detailed the November 15, 1959 quadruple murder of the Clutter family by Richard “Dick” Hickock and Perry Edward Smith during a home-invasion robbery in rural Kansas, later immortalized on film by Richard Brooks with Robert Blake and Scott Wilson as the perpetrators. More recent, and more close to home for genre fans was the 2007 home invasion that took animator Helen Hill in New Orleans, in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. While temporarily displaced after the hurricane, she was involved with grassroots activist groups determined to rebuild the city. On the morning of January 4th, 2007, an intruder broke into their house, murdered Helen and shot her husband Paul Gailiunas three times. Gailiunas survived, and posthumously completed Helen’s final film The Florestine Collection, incorporating this tragedy into the film.

That isn’t to say this is a new phenomena. One of the most notorious home invasion cases became the basis for Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, which detailed the November 15, 1959 quadruple murder of the Clutter family by Richard “Dick” Hickock and Perry Edward Smith during a home-invasion robbery in rural Kansas, later immortalized on film by Richard Brooks with Robert Blake and Scott Wilson as the perpetrators. More recent, and more close to home for genre fans was the 2007 home invasion that took animator Helen Hill in New Orleans, in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. While temporarily displaced after the hurricane, she was involved with grassroots activist groups determined to rebuild the city. On the morning of January 4th, 2007, an intruder broke into their house, murdered Helen and shot her husband Paul Gailiunas three times. Gailiunas survived, and posthumously completed Helen’s final film The Florestine Collection, incorporating this tragedy into the film.

The cinematic roadside is dotted with defiant home invasion films –Straw Dogs (1971), Fight for Your Life (1977), Fair Game (1986), Funny Games (1997), Inside (2007)– and a recent resurgence has brought a pair of such films together for the program at this year’s Fantasia – Jed Strahm’s Knifepoint and Miguel Angel Vivas’ Secuestrados /aka Kidnapped – alongside an unsung classic of the genre, William Fruet’s Death Weekend (1976), the latter screening as part of this year’s tribute to John Dunning and Andre Link’s Cinepix Films.

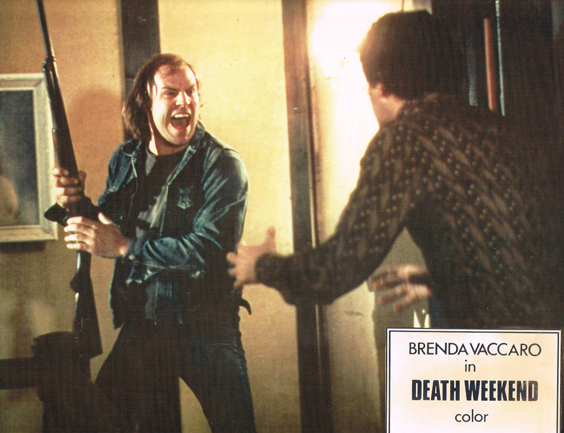

To quote my own synopsis of Death Weekend (which can be read in full on the film page HERE): When Diane (Brenda Vaccaro of Midnight Cowboy) runs hick gangleader Lep (Don ‘The Cloud’ Stroud) and his slobbering crew off the road in a high-speed pursuit down an isolated country road, it initiates the most frenzied and brutal tale of retribution produced in cinema’s tax-shelter golden age. Leaving the rural ruffians in the dust, Diane and her companion for the weekend, wealthy dentist Harry, head off to his remote lakeside mansion, where she quickly discovers that she’s sequestered herself with a total creep. Meanwhile, Lep and his goons have discovered their whereabouts and are bent on revenge.

As with other home-invasion/rape-revenge crossover flicks like Straw Dogs, Open Season (1974) and Last House on the Left (1972), class and gender struggle go hand in hand — it’s the haves versus the have-nots. But Death Weekend stands apart from its brutes-versus-bourgeois brethren in its characterization of the upper class as equally suspect. As the home invasion degenerates into a jaw-dropping flurry of destruction and personal violation, one suspects the protagonists’ privilege is what the antagonists really find so offensive. But trapped in this convergence of raging testosterone, Diane refuses to fit the stereotype the men have molded for her. It takes a hell of a woman to go up against a lumbering menace like Don Stroud, and Vaccaro delivers on all counts. (Death Weekend screens July 27th at 7pm at the Cinematheque quebecoise)

Spanish director Miguel Angel Vivas is known to Fantasia fans for his award-winning short I’ll See You in my Dreams (later released on Fantasia’s Small Gauge Trauma DVD compilation via Synapse Films) and his latest home invasion thriller Secuestrados (aka Kidnapped) is a nasty and uncompromising piece of work (screening Aug. 1, 7pm + Aug. 2, 3pm in the Hall Theatre). In a film like the ferocious Secustrados, the class struggle that clearly exists in Death Weekend is not as pronounced. Yes, the victims are targeted because they are wealthy, but the assailants themselves appear to have a recurring, successful system bolstering their criminal actions. They’ve been doing this long enough to be rather well-off themselves. In a sense this lack of psychology is more terrifying. Their face-obscuring balaclavas emphasize this emotional inaccessibility, and the film’s composition out of only a dozen prolonged takes relentlessly throws us right into the maelstrom with the victims, whose attempts to reason with these faceless attackers elicits no result save for increased personal injury.

Jed Strahm’s Knifepoint (making its World Premiere at Fantasia on July 16th, 11:55pm and screening again July 24th, 9:45pm, both in the Salle J.A. DeSeve) blends the criminal profiling of Death Weekend and Secuestrados, fashioning an organized crime outfit run by complete psychopaths. In Knifepoint, Abbie (Katherine Randolph) and her wheelchair-bound sister Michelle (Krista Braun), who secretly resents her more independently mobile counterpart, are alone in their condo when a drooling thug breaks in and begins sexually assaulting Michele. With the assailant quickly dispatched via a blow to the head, the girls soon realize that the rapist was only the sentinel for a gang descending upon their home as part of a large-scale robbery targeting the entire complex.

With both Death Weekend and Knifepoint, we can see where the assailants’ weak points are – in identifying with the victims, we can see the power dynamics that exist within their group, and possible means of exploiting that. The female relationships in Knifepoint are especially interesting because they are imbued with residual anger and paranoia; the psychotic female assailant Lorraine (Kym Jackson) doesn’t seem that much different from Michele if you take a step back and analyse their psychology – both are in primary relationships that place them in a position of dependence and weakness, and frustration gets acted out in unhealthy ways – usually against the other female characters. When Abbie and Michele – ostensibly the two victims – show any sign of agency or independence, Lorraine becomes especially retributive: she takes it not only as a physical threat but a threat to her integrity. It calls into question her own inability to stand up for herself in pivotal situations.

With Secuestrados, on the other hand, the motive for the crime and for the characters’ actions is purely financial, and rape is seen as something that is just a by-product of the home invasion. It does not actually give us a window into the minds of the antagonists. Even in Haneke’s Funny Games, we can’t help but search for some clue, some past trauma, something that has brought these assailants to this home on this day. We don’t get these answers, to be sure, but we are driven to look for them nonetheless.

But most of all, the home invasion film speaks to the transferring of a threat from the public space to the private space – the latter giving the false impression of being ‘safe’ – and how we adjust to that threat. These assailants are mobile, and they will come to you if they want what you have. As in most horror films and revenge films alike, asserting and defining control is a fundamental concern. And while any type of violence signifies a lack of (emotional and/or physical) control in real life, in genre films the opposite holds true: that transformative moment when a pacific protagonist reaches for the weapon is a moment of clarity that is often loudly applauded by an audience. Which is why no matter how realistic the films may be, they are always grounded in fantasy by the emotions they elicit, which would often be inappropriate in real life.

It’s also worth reiterating that the most assertive characters in these particular films are women, which is especially inspiring given that women’s personal space issues are more pronounced than her male counterparts’. Women are constantly negotiating their use of space, the right to explore that space as opposed to shrinking from it as threats close in. Where Straw Dogs is about a man’s right to defend his property (and yes, that includes Susan George), all three films discussed here – Death Weekend, Secuestrados and Knifepoint – deal explicitly with a woman’s right to inviolable space.

These films are all significantly different approaches to the home invasion subgenre, and between them we get a succinct snapshot of the genre’s evolution, the stereotypes and Darwinian tropes they alternately challenge or reinforce, and the subversive potential that can reverberate in real life.

—————-

Knifepoint has its World Premiere on July 16th at 11:55pm and screens again on July 24th at 9:45pm, both in the Salle J.A. DeSeve. More info on the film page HERE.

Death Weekend screens July 27th at 7pm at the Cinematheque quebecoise. More info on the film page HERE.

Kidnapped (Secuestrados) screens Aug. 1, 7pm and Aug. 2, 3pm in the Hall Theatre. More info on the film page HERE.

July 16, 2011

July 16, 2011

Comments