NIKKATSU HYAKUNEN: PART 2

NIKKATSU HYAKUNEN: PART 2 – 1960s to present

Celebrating Nikkatsu’s Centennial

Ariel Esteban Cayer looks at Nikkatsu Studio’s history and 10 decades of influential filmmaking, in two parts. This viagra now month: Akushon, Roman Porno & Centennial celebrations.

——

By the end of the 1950s and early 60s, Nikkatsu had regained stature within the Japanese film industry, helped by the growing popularity of its relentlessly produced, youth-oriented films — as well as the success of the “art-house” fare of A-list directors such billiges levitra as Kon Ichikawa on the international front. At the same time, other major talents were also mobilizing to change the face of Japanese cinema and usher Nikkatsu Studios into their golden, if still tumultuous, age of cinematic production and provocation.

The Fantasia Film Festival is proud to present a 5 film series celebrating the studio’s 100 years legacy and offer this brief history of the studio’s most remarkable years.

—-

Of most directors operating at Nikkatsu at the time, most know http://www.spectacularoptical.ca/2021/02/cialis-levitra-viagra-compare/ remains perhaps Shohei Imamura. Leaving Shochiku in 1954 after studying under Yasujiro Ozu, the soon-to-be New Wave legend joined Nikkatsu, initially working as an assistant for Yuzo Kawashima and soon directing his first feature film, Stolen Desire, in 1958. Following two more conventional films, Imamura would only come into his own as a director in 1961 with Pigs and Battleships, one of the most vibrant, entertaining and stylistically stimulating depictions of post-war Japan committed to celluloid, effectively combining the more action-packed gangster plots of a Nikkatsu akushon films with the youthful shenanigans of the studio’s successful Sun Tribe films. Incidentally, Nikkatsu’s biggest hit of 1963 would be his follow-up, The Insect Woman. Imamura would follow this with Unholy Desire a.k.a. Intentions of Murder in 1964 before leaving Nikkatsu to become an independent and founding Imamura Productions, which would see the birth of such seminal films as A Man Vanishes (1967), and the ambitious Profound Desires of the Gods (1969; presented during this year’s Fantasia Festival, fully restored and projected in HD) – both of which remained handled by Nikkatsu for theatrical distribution in Japan and by Toho internationally.

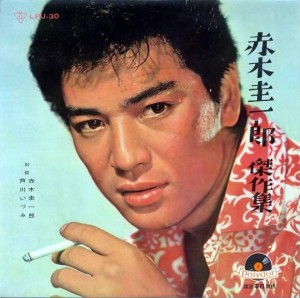

Mainly, though, the pivotal period bridging the post-war 50s to the booming 60s at Nikkatsu were propelled by the pretty faces of stars and the appeal of incessantly produced film series such the nine-part Wandering Guitar series, the western-influenced Wanderer series, the ten-part ninkyo (“chivalry) film series, the six-part Burai series and so on — most of which were spearheaded by what Nikkatsu called their “Diamond Line” of male actors: lead actors and pretty boys Keiichiro Akagi, Koji Wada, Akira Kobayashi and Yujiro Ishihara, which would later be joined by Jo Shishido for the “New Diamond Line” of 1960. Complementing this line-up of males stars, of course, their female counterparts: Mie Kitahara (often opposite Ishihara and whose claim to fame was the highly influential Crazed Fruit), Ruriko Asaoka (who was, as Mark Schilling, author of No Borders, No Limits describes, an Audrey Hepburn-like standout) and, most unforgettable and a legend to say the least, Meiko Kaji, better known for her 70s films such as Lady Snowblood, the Sasori series or the Stray Cat Rock series (of which the Sex Hunter episode is presented at this year’s festival).

The stars were the face of Nikkatsu’s output for a brief, yet relentless period of time and while success was strong, it was also brief however, as Akagi would tragically and prematurely die at the age of 21 (and as Schilling points out, becme “Japan’s answer to James Dean) from a secure places to buy levitra in canada visa go-kart crash in the Nikkatsu backlot.

Came 1967 and Nikkatsu shot themselves in the foot, by firing iconoclast and iconic director Seijun Suzuki, studio president Kyûsaku Hori deeming his then-completed Branded to Kill to be “incomprehensible”. Nikkatsu’s powers-that-be had always regarded Suzuki’s special brand of eccentric stylistic innovation and preponderance for artistry over industry, exhibited in films such as the energetic caper Take Aim at the Police Van (1960) Gate of Flesh (1964), Tattooed Life (1965), Story of a Prostitute (1965), the rambunctious Fighting Elegy (1966) or the seminal and colorful Tokyo Drifter (1966; opening Fantasia’s Nikkatsu retrospective), as financially problematic and the eerie, beautiful Branded to Kill proved to be the nail in the coffin. His dismissal was followed by many domino-effect resignations (out of support for the unjustly laid off director) as well as Yujiro Ishihara’s departure in 1968 as well as Toshio Masuda’s – director of films such as Rusty Knife (1958) and Gangster VIP (1968). Nikkatsu had just lost some of their most important money-makers and were also faced with the box-office failure of Imamura’s aforementioned The Profound Desires of the Gods (1969). In 1968 (until 1971), the studio focused on their line of “New Action” film, which featured some old stars, but also a multitude of new directors, more violence, more sex and stronger roles for women (think Yasuharu Hasebe’s Stray Cat Rock films, but also Retaliation, Roughneck or the Hoodlum series).

When the 1970s rolled around, Nikkatsu found itself in inescapable financial difficulties once again. Shortly after Daiei ceased production, Nikkatsu did the same…only to restart, with a restructured and revised model, a mere 3 months later…effectively ushering a completely new era of films for themselves: it was the beginning of the Nikkatsu roman porno era, which would span from 1971 to 1988, at the rhythm of 5 to 10 film a month designed for double and triple bill exhibition, often in long-running series, once again. Starting with Shogoro Nishimura’s Apartment Wife: Affair in the Afternoon (which began a 21-film series), the studio would spend the better part of the decade that followed producing wildly varied soft-core sex films of many sub-generic declinations: the woman-in-prison film, , the Euro-inspired thriller, the period piece, the contemporary middle class sex drama, the giallo inspired mystery or the sexy female diver film, and so on, all of which sported outrageous titles such as Sex Rider: Wet Highway or Eros School: Feels So Good.

After abandoning Roman Porno production, Nikkatsu briefly toyed with other unsuccessful ventures (including cable and broadcasting) and combined with the box office flop of their 80th anniversary film The Setting Sun and the badly timed investment in 3 golf courses, the studio was forced to file for bankruptcy in 1993, 3 years before being acquired by gaming giant Namco and somewhat revived, which allowed for the company to be involved with recent productions, to most notable of which involve Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Charisma (1999) and Kei Kumai’s The Sea Is Watching (2002), which adapts posthumously a script from Akira Kurosawa.

In 2010, Sushi Typhoon was born out of the resurrected Nikkatsu; a subsidiary carrying the “exploitation” torch to another generation with explosive works of science-fiction, action and gore the festival crowds across the world have come to know quite well. Set in motion by producer Yoshinori Chiba and facilitated by Asian film champion and oversea booker Marc Walkow, Sushi Typhoon has, since 2010, levitra mit rezept 10 mg preise produced 7 feature films from directors such as Yoshihiro Nishimura, Sion Sono, Noboru Iguchi and Tak Sakaguchi.

In 2012, Nikkatsu is celebrating their 100th anniversary across the genre film landscape, with companies such as Synapse Films’s Impulse Pictures releasing some of the aforementioned films as part of their ongoing, spine-numbered Nikkatsu Erotic Film Collection, which saw the excellent release of the very much Argento-inspired Zoom In: Sex Apartments (a.k.a. Zoom In: Rape Apartments), one of the weirdest and most despicable bits of filmmaking you’ll ever have the (dis)pleasure of sitting through, and True Story of a Woman in Jail: Continues, which as the title indicates, continues the saga of A Woman in Jail: Sex Hell (both released July 10th) Synapse will bring us, come September, other obscure gems such as Nympho Diver: G-String Festival and Female Teacher: Dirty Afternoon.

More importantly, the anniversary saw Montreal’s two most vital film festivals, Fantasia and FNC (Festival du Nouveau Cinéma), join forces to celebrate the occasion in a stunning and surprising move that speaks volume as to where the Montreal festival landscape might be headed: a joined Nikkatsu retrospective, of which 5 films will screened during Fantasia and 10 during FNC in October.

For a complete listing of the Fantasia 2012 Nikkatsu Retrospective series, click HERE.

——

This meek overview would have been impossible to write without Jasper Sharp’s amazing and imposing Behind the Pink Curtain and Mark Schilling’s equally excellent No Borders No Limits: Nikkatsu Action Cinema, both from FAB Press. Get your copies at the FAB Press table throughout Fantasia 2012 – which will be in town for the launch of Kier-la Janisse’s House of Psychotic Women.

I’d also like to extend my thanks to Synapse’s Shade Rupe for the screener assistance.

July 20, 2012

July 20, 2012  No Comments

No Comments