SHE DIED WITH HER BOOTS ON

SHE DIED WITH HER BOOTS ON: THE WOMEN OF THE EURO-WESTERN

Kier-La Janisse

————————–

Please note in keeping with the terminology of the films, the word ‘Indian’ is used throughout to refer to Aboriginal and Native female viagra next day delivery American characters.

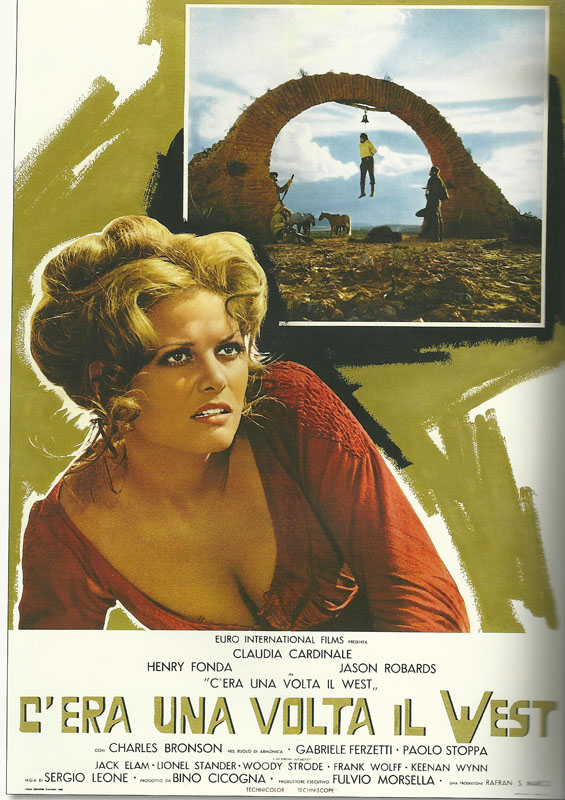

As with their American counterparts, the euro-westerns had no shortage of beautiful women. But in this hyper-masculine genre, it was rare for women to function as anything beyond glittering accessories in an otherwise bleak terrain; compared to the sexual dismissiveness of the euro-western, the misogynistic spectacle of the giallo seems almost reverential. If she’s lucky, men might fight over her, giving her a catalystic role for the macho action that the western prefers. Barmaids, hostages and whores are the most common roles for women in the genre, and of the latter, the proverbial hooker-with-a-heart-of-gold (Claudia Cardinale’s Jill McBain in Once Upon a Time in the

West, Lynne Frederick’s Bunny in Fulci’s Four of the Apocalypse, both inspired to some extent by Katy Jurado’s Helen Ramirez character in High Noon) and her opposite, the conniving gold-digger (Femi Benussi in Requiem for a Gringo, Linda Veras in Sabata, Nieves Navarro in the Ringo films) were coveted – if still questionable – roles for European B-movie actresses of the best discount cialis time.

Claudia Cardinale in Once Upon a Time in the West (image from Kevin Grant’s book ‘Any Gun Can Play’)

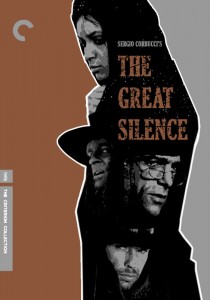

Among the more respectful depictions of women in the spaghetti western canon are Sergio Corbucci’s The Great Silence (1968) and the Argento co-scripted Cemetery without Crosses of the following year. In both films, the female leads prove to be stoic influences on the trajectories of their troubled gunfighters (Jean-Louis Trintignant and Robert Hossein, respectively); The Great Silence in particular sees Vonetta McGee hire the mute drifter Silence (Trintignant) to avenge her husband’s death and the two develop a tender romantic relationship (and an uncharacteristically interracial relationship at that) underscored by a strong mutual sense of integrity. Following a similar plotline, Cemetery Without Crosses (aka The Rope and the Colt, which is also the name of the Scott Walker-crooned theme song) sees Michele Mercier turn to an old family friend (Robert Hossein, who also directed) to avenge her husband’s death, knowing that he harbours a longtime love for her. Both of these films are among the most melancholic of the genre (due in part to their apocalyptically desolate settings), with their get levitra over night delivery tentative romances doomed by the surrounding circumstances of death and revenge.

Among the more respectful depictions of women in the spaghetti western canon are Sergio Corbucci’s The Great Silence (1968) and the Argento co-scripted Cemetery without Crosses of the following year. In both films, the female leads prove to be stoic influences on the trajectories of their troubled gunfighters (Jean-Louis Trintignant and Robert Hossein, respectively); The Great Silence in particular sees Vonetta McGee hire the mute drifter Silence (Trintignant) to avenge her husband’s death and the two develop a tender romantic relationship (and an uncharacteristically interracial relationship at that) underscored by a strong mutual sense of integrity. Following a similar plotline, Cemetery Without Crosses (aka The Rope and the Colt, which is also the name of the Scott Walker-crooned theme song) sees Michele Mercier turn to an old family friend (Robert Hossein, who also directed) to avenge her husband’s death, knowing that he harbours a longtime love for her. Both of these films are among the most melancholic of the genre (due in part to their apocalyptically desolate settings), with their get levitra over night delivery tentative romances doomed by the surrounding circumstances of death and revenge.

But there are very few instances of a female equivalent to The Man with No Name – the squinting, morally-ambiguous but appealing anti-hero that lies at the centre of most eurowesterns. In the world of the frontier, it’s not uncommon for a woman to pick up a gun, but to be good at using it is another matter altogether. Below are some of the most memorable female characters I’ve encountered in the genre, but even they leave much to be desired as far as positive gender representation.

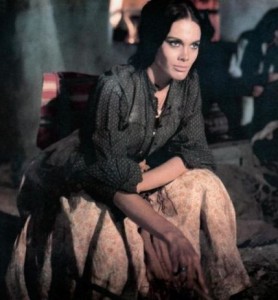

Nicoletta Machiavelli in Navajo Joe. She never picks up a gun once in the film – this is a staged publicity still.

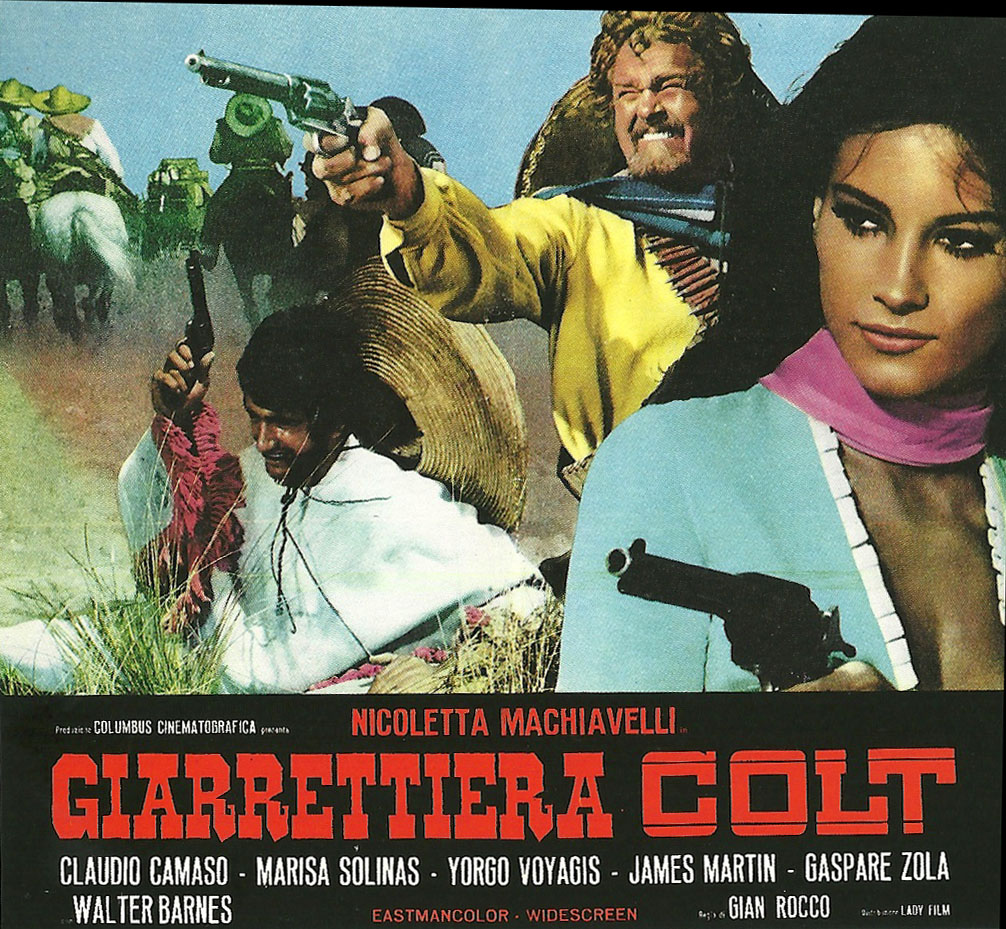

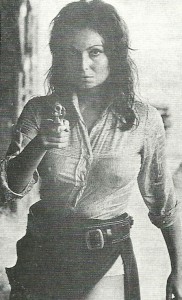

Actress Nicoletta Machiavelli did her time in the euro-western with gusto, in addition to numerous roles in poliziotteschi (and even a turn for Zulawski in L’important c’est d’aimer in 1975). After a breakout as the half-breed Indian servant girl who helps Burt Reynolds defeat a gang of racist marauders in Sergio Corbucci’s Navajo Joe (1966), she won a leading role as the titular gun-slinging card shark of Gian Andrea Rocco’s Garter Colt (1968). Her dialogue is limited in Navajo Joe, which is explained by an innate stoicism; her rebellion against the people who have spent years domesticating her is all in her eyes. But her third-billing (not to mention her stunning beauty) likely increased her marquee status, allowing for a rare star turn in a male-oriented genre with Garter Colt two years later (a project she initiated). That’s not to say that she isn’t presented as eye-candy and that the camera doesn’t linger on her ample bosom at every opportunity, but nothing can undermine her confidence and charisma here (although the circus-y score by Giovanni Fusco and Gianfranco Plenizio makes a valiant effort). Seen as “an homage to feminism”[i], the film was a timely move for both its director and star. But strangely its political sentiment takes a 180 from Navajo Joe: in Garter Colt, the Mexicans are demonized as barbaric bloodthirsty brutes and bandits while the film sympathizes with the French colonizing soldiers.

Machiavelli plays Lulu, who travels through the US-Mexican borderlands (actually Sardinia) looking for a good card game, while a gun with a heart-shaped barrel lies tucked away in her garter belt beneath her billowy skirts (thus her nickname ‘Garter Colt’). She holds a neutral position in the revolution springing up around her, until she falls in love with Carlos, a French soldier who is disguised as a Mexican in order to infiltrate and halt a drug-smuggling trade. Of course, with Garter Colt

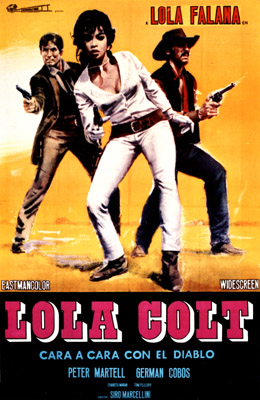

being our protagonist, she can’t just fall into his arms like a swooning maiden – her foreplay consists of shooting at him and seductively cheating at cards against him. When he is exposed as a Frenchman in disguise and captured by the Mexicans, it is Garter Colt who races to his rescue, in a fantastic sequence where her hair and clothes flow freely in the breeze behind her, perfectly framing the gun strapped to her thigh. Finally the two consummate their love in a surprisingly (and disappointingly) sexless scene,  and Carlos tries to convince her to give up her roguish ways and settle down with him in a life of domestic tranquility. Luckily he’s killed soon after, allowing her to remain a hardened heroine. Unfortunately, as unshakable as Machiavelli is, her character is not fleshed out enough to be anything but a novelty act. The same can be said of Lola Falana’s role in Lola Colt (1967); as a travelling dancer who straps on a gun to lead a small town in an uprising against the local crime boss, she gets the spotlight, but the film is primarily a vehicle for her anachronistic musical performances more than any attempt to stake out a woman’s place in the genre.

and Carlos tries to convince her to give up her roguish ways and settle down with him in a life of domestic tranquility. Luckily he’s killed soon after, allowing her to remain a hardened heroine. Unfortunately, as unshakable as Machiavelli is, her character is not fleshed out enough to be anything but a novelty act. The same can be said of Lola Falana’s role in Lola Colt (1967); as a travelling dancer who straps on a gun to lead a small town in an uprising against the local crime boss, she gets the spotlight, but the film is primarily a vehicle for her anachronistic musical performances more than any attempt to stake out a woman’s place in the genre.

I had high hopes going into Sonny and Jed (1972), hailing as it did from Sergio Corbucci who gave us Navajo Joe (1966, the same year he made the seminal Django) and The Great Silence (1968), even though this later effort starred probably my most detested actress of the period – Susan George. But assuming that her many annoying film roles were merely performed as they were meant to be based on their respective scripts, I was willing to give her the benefit of the doubt, especially as she’s paired romantically here with the most hilarious over-actor of the Italian exploitation boom – Tomas Milian.

George stars as Sonny, the granddaughter of the recently-departed grave-digger of a small western town. Seeing the limited fate of women in her world (marrying a rich slob or becoming a prostitute), Sonny wants desperately to be a boy, wearing her hair up in a hat and dressing in bulky men’s clothes that hide her girlish figure. After a chance meeting with Jed Tregado (Milian) – a notorious Robin Hood-type who steals from rich white landowners to give back to the meek Mexican families that depend on him for protection – she decides that an outlaw’s life is the way to go if she expects any degree of freedom. But even when he realizes she’s a woman, Jed fails to look at her as anything other than a whiny, clumsy tagalong who – as an awkward virgin – isn’t even experienced enough to provide a handy sexual outlet for his brutish desires. She can’t fight, can’t shoot, and – as Jed eagerly points out – can’t even spit, and he is about to sell her to a whorehouse when she breaks down and confesses her love for him. This catches him off-guard, and he momentarily melts (“No one ever said that to me before”), and has a change of heart. After an impromptu wedding, the two hit the trails as a Bonnie and Clyde-type duo, robbing banks and holding up jewellery stores. But he still just looks upon her as an appendage that he can warm up next to at night, which becomes apparent when he spies a rich woman with big jugs and decides that she’s where it’s at, resulting in a sloppy romp in the hay. Sequences such as these and Jed’s routine vulgar verbal lashings at Sonny – which humiliate George’s character at every turn – are meant to be humourous, but are just one more example of how Susan George routinely plays the punching bag with the cutie-pie face. Memorable, yes. Recommended, no.

Romolo Guerierri’s Johnny Yuma (1966 – co-written by eurocrime king Fernando Di Leo) takes the troubled hero of the TV western show The Rebel and transforms him spaghetti-style into a philandering anti-hero (played by Mark Damon) who is on his way to take over operations of his disabled uncle’s farm when he gets news that his uncle has been murdered. In an early role for screen siren Rosalba Neri, she plays Samantha Felton, the gold-digging widow who had her brother kill her husband and then framed her Mexican servant/lover for the crime, hoping to get her hands on her husband’s fortune. But when it is revealed that the estate has been left in full to his nephew Johnny Yuma, she calculates an elaborate plan to bump him off, roping in an ex-lover and expert gunfighter (Lawrence Dobkin, the narrating voice on TV’s Tales of the Naked City) to take care of business. She’s a double-crosser extraordinaire, and plays the various characters against each other so that she will be the last one standing with the piles of money her husband left behind. And she’s not against employing a weapon or two herself when the need arises, which gives the viewer ample fetishistic imagery of a sadistic villainess in action. While the manipulative woman is another of the genre’s stereotypes, Neri does it so capably that it does make her the center of the film, drawing attention away even from the eponymous protagonist.

But even the image of Neri commanding Johnny Yuma’s corrupt plot can’t match what Patty Shepard does in less than ten minutes of screentime in Peter Collinson’s The Man Called Noon (1973). Collinson’s previous foray into Italian culture came via his caper The Italian Job (1969) and this film has an equally international flavour, being a three-way co-production between Spain, Italy and the UK, with an American lead (Richard Crenna). Based on a Louis L’Amour pulp western, Crenna stars as Rubble Noon, an infamous bounty killer who loses his memory after being ambushed by fellow outlaw Ben Janish. With the help of cowboy J.B. Rimes (Stephen Boyd) he makes his way to the ranch of Fan Davidge (Rosanna Schiaffino of The Witch) who has been forced by Janish to turn her property into a hideout for his henchmen. But she’s far from a victim – she does what she has to do to survive, with no regret or self-pity. Not remembering his reputation for being merciless, Noon treats Fan with respect that gradually wins her affection.

As Noon starts to get his memory back and realizes that he knows the location of a mountain of hidden gold, he starts to piece together the who-and-why of the attempts on his life. The gold was left in Noon’s care by a man named Cullane, who was murdered by a corrupt Judge (Farley Granger)

in cahoots with the late Cullane’s own sister, Peg (Patty Shepard). When Peg first appears onscreen she is in faux-mourning and moves with the slow-motion distractedness of a person in shock. But this is a front, and as soon as she realizes that Rubble is onto her, she switches into full-on villainess mode and changes into fitted all-black bandit gear for a final showdown with Rubble, Rimes and Fan. “You wouldn’t shoot a woman,” she says to Rimes, whose gun is fixed on her, “You haven’t got the guts!” Fan takes this as her cue, training her own gun on Peg in a scene that’s a direct riff on Nicholas Ray’s Johnny Guitar (1954): “But I have – I’d shoot you and I’d enjoy it, murderous bitch!”

Both Fan and Peg are atypically strong female characterizations in the context if the spaghetti western, but it’s Patty Shepard as the heartless Peg Cullane who steals the show (I should disclose my own bias: I would watch Patty Shepard watching paint dry. She has a fantastic screen presence and deserves to be a much bigger star in the eurotrash pantheon).

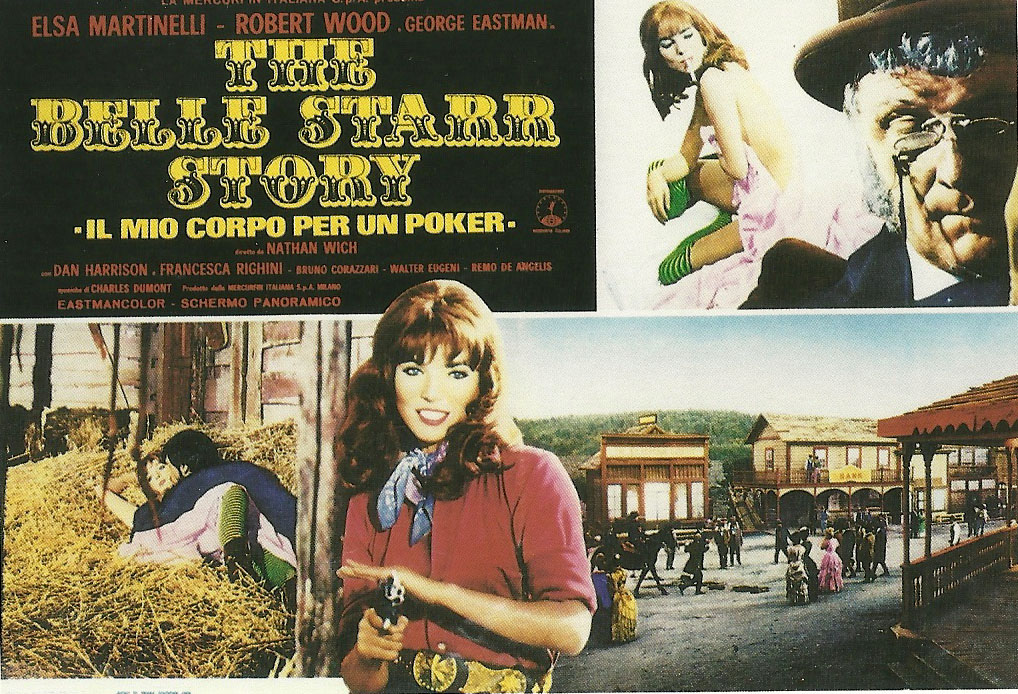

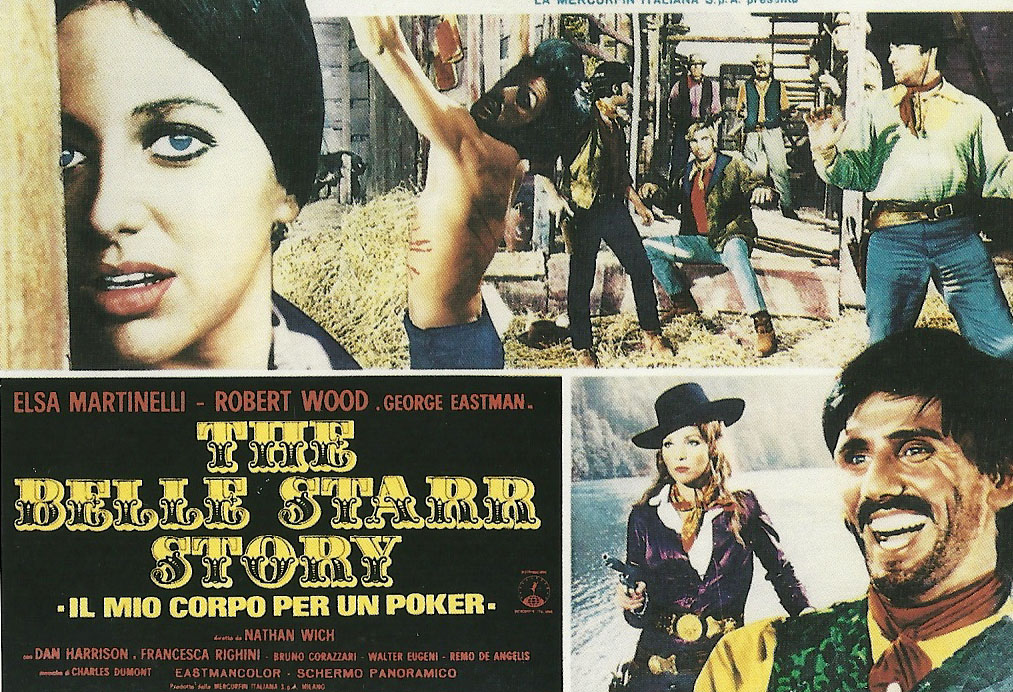

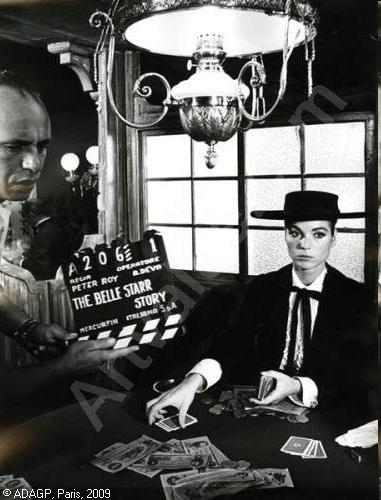

One of the rare westerns to be written by a woman[ii] – in this case Lina Wertmuller, who also took over direction part way through filming – is The Belle Starr Story (1968), which prefigures the controversial gender politics of Wertmuller’s later film Swept Away (1974). Elsa Martinelli plays a fictionalized version of real-life American outlaw Belle Starr, a transient wanted woman who is first seen at a card table dressed in all-black men’s garb and smoking a cigar. Eurotrash regular George Eastman plays fellow outlaw Larry Blackie, who joins the card game saying with unveiled condescension: “You must be that gal that dresses like a fella everybody’s talking about – you don’t look so dangerous. You’re even pretty.” She deliberately loses at poker against him, throwing away good cards even though she knows that once her money is all gone, her virtue is on the line. But when they go up to a private room so he can collect his winnings, she gives him mixed messages, fighting him half-heartedly so that he has to “rape” her, which he catches onto, saying “What, do you need an excuse?” After giving in to a night of rapturous lovemaking, the next morning he mocks her when he finds out that she’s the infamous Belle Starr and yet she allowed herself to be treated as a whore.

Instead of moving onto the next town, she vows to stay in his turf, in order to get revenge on him for this humiliation. This is the beginning of a push-pull relationship that will be romanticized throughout the film, as he softens her up, she succumbs to her increasing feelings for him, he rejects her and she tries unsuccessfully to hurt him. Even though flashbacks reveal her to be an experienced gunslinger, as a woman she is still depicted as being ruled by passion and over-emotionalism. In one of their tender moments she confesses to him, “Belle Starr doesn’t exist. She’s just a cover to hide what’s left of a life gone wrong.”

The film is problematic on a number of levels, most notably in that it succeeds in romanticizing an unhealthy relationship in which the woman is always the loser. Larry Blackie is a despicable person, but he’s also incredibly charismatic and it’s not hard to see how she could fall for him, especially when the added excitement of professional competition is thrown into the mix. Because the story is told from her perspective, we can see how she feels about Blackie, whereas his own motivation is less obvious. He just seems to enjoy using her emotions against her. But she chooses to engage with him on this level – it’s clear that she can survive on her own, that she’s uniquely skilled and intelligent, but her capabilities seem to wilt in his presence, making her a bizarre representation of a potentially feminist character that is nonetheless in line with Wertmuller’s other work.

The film is problematic on a number of levels, most notably in that it succeeds in romanticizing an unhealthy relationship in which the woman is always the loser. Larry Blackie is a despicable person, but he’s also incredibly charismatic and it’s not hard to see how she could fall for him, especially when the added excitement of professional competition is thrown into the mix. Because the story is told from her perspective, we can see how she feels about Blackie, whereas his own motivation is less obvious. He just seems to enjoy using her emotions against her. But she chooses to engage with him on this level – it’s clear that she can survive on her own, that she’s uniquely skilled and intelligent, but her capabilities seem to wilt in his presence, making her a bizarre representation of a potentially feminist character that is nonetheless in line with Wertmuller’s other work.

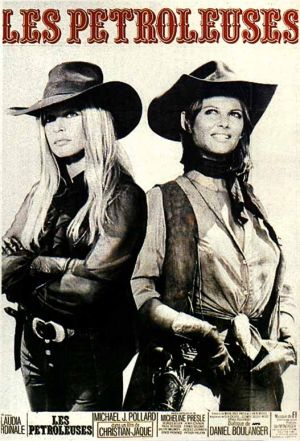

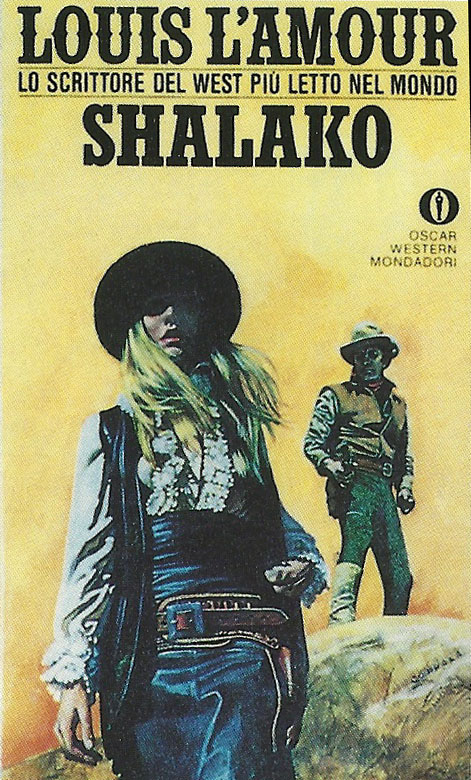

Riffing on the earlier Viva Maria! (1965), which paired screen icons Brigitte Bardot and Jeanne Moreau in a burlesque revolutionary romp circa the turn of the last century, The Legend of Frenchie King (1971) sees Bardot pitted against Claudia Cardinale as two female gunfighters after the same plot of land reputed to be brimming with oil. Bardot was no stranger to the eurowestern, not only from Viva Maria but also Edward Dmytryk’s Shalako, a 1968 UK/West German co-production based on a Louis L’Amour story. Despite her character often gracing the book covers and film posters, Bardot isn’t the ‘Shalako’ of the title – that moniker belongs to Sean Connery, who even as a former ‘Bond’, withers beside the heat emanating from Bardot.

Riffing on the earlier Viva Maria! (1965), which paired screen icons Brigitte Bardot and Jeanne Moreau in a burlesque revolutionary romp circa the turn of the last century, The Legend of Frenchie King (1971) sees Bardot pitted against Claudia Cardinale as two female gunfighters after the same plot of land reputed to be brimming with oil. Bardot was no stranger to the eurowestern, not only from Viva Maria but also Edward Dmytryk’s Shalako, a 1968 UK/West German co-production based on a Louis L’Amour story. Despite her character often gracing the book covers and film posters, Bardot isn’t the ‘Shalako’ of the title – that moniker belongs to Sean Connery, who even as a former ‘Bond’, withers beside the heat emanating from Bardot.

Bardot is the visual fixation of Shalako, but also the catalyst for its plot. She’s a countess visiting America with a group of wealthy Europeans who hire Stephen Boyd (ironically the first choice to play the inaugural 007 in Dr. No) as a guide through the rough terrain of the American west, where they hope to hunt some endangered animals and maybe even see a real Indian. When Bardot proves herself an expert hunter and wanders off into protected Indian land, the angered Indians give them 12 hours to vacate their makeshift camp or they come in fighting. Bardot’s character Irena is apologetic and wants to retreat, but her proud, priggish compatriots refuse, causing an all-out, wholly unnecessary battle between the two parties in which the Europeans must turn to ex-Army man Shalako to save them, against his better judgement.

Bardot is the visual fixation of Shalako, but also the catalyst for its plot. She’s a countess visiting America with a group of wealthy Europeans who hire Stephen Boyd (ironically the first choice to play the inaugural 007 in Dr. No) as a guide through the rough terrain of the American west, where they hope to hunt some endangered animals and maybe even see a real Indian. When Bardot proves herself an expert hunter and wanders off into protected Indian land, the angered Indians give them 12 hours to vacate their makeshift camp or they come in fighting. Bardot’s character Irena is apologetic and wants to retreat, but her proud, priggish compatriots refuse, causing an all-out, wholly unnecessary battle between the two parties in which the Europeans must turn to ex-Army man Shalako to save them, against his better judgement.

But where Bardot sleeks across the screen in Shalako, she really gets to play in Frenchie King, which would prove to be one of her final roles before retirement. She heads up a black-clad, all-girl gang of train robbers (including in its numbers Spanish exploitation faves Emma Cohen and Patty Shepard of A Man Called Noon) , who laugh loudly, rob indiscriminately, and behave in a disorderly, unladylike fashion – although they can (and do) be prim and proper when a particular ruse calls for it. Michael J. Pollard plays the adorable but ineffectual sheriff who is hopelessly infatuated with Miss Maria (Claudia Cardinale), an outlaw rancher

who lives alone with her four dimwitted brothers. When Miss Maria finds a treasure map declaring a nearby plot of land to be full of oil, she makes a bid on the land only to be told that a female doctor has recently arrived in town holding the deed to the property. Suspecting that the ‘doctor’ is in fact Frenchie King under a false identity, Maria engages in a battle of wits and wills with Frenchie, which results in some rather hilarious catfights. Make no mistake: if you want to see two of the hottest women of European cinema duke it out in tight clothes, look no further than Frenchie King.

Still, even though the world of Frenchie King and her cohorts (as well as that of Raquel Welch vehicle Hannie Caulder) depicts men as bumbling idiots that are nothing more than toys for the occasional teasing or bedroom tryst, the woman gunfighter is still portrayed as a novelty, and rarely taken as seriously as her male counterparts would be in a similar film. Frenchie King is host to some amazing, empowering imagery but it’s largely superficial imagery ripped from trendy feminist slogans and bastardized by an exploitation context. (And of course I loved every minute of it!)

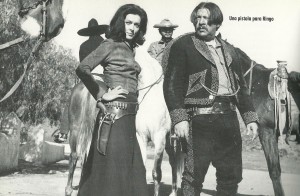

Perhaps the best example of progressive female characterization comes, not surprisingly, in Damiano Damiani’s A Bullet for the General/Quien Sabe? (1966). Quien Sabe? is universally lauded as one of the best of the spaghetti westerns, with its highly political and emotionally rich storyline courtesy of Salvatore Laurani and Franco Solinas – the latter being the fervently communist writer behind Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers. When a group of Mexican bandits headed up by El Chuncho (Gian Maria Volonte) rob a train carrying arms in order to sell the weapons to the revolutionaries, the well-to-do gringo passenger Bill Tate (Lou Castel) decides to help them, with the two forming an unlikely alliance that borders on friendship (and with a mutual fascination that borders on homoeroticism). But between the story of these two men is the fiery, cigar-chomping Mexican revolutionary Adelita (a post-Bond, pre-Hammmer Martine Beswick), a formidable character and the only one suspicious of Tate’s less-than-honourable motives. She is portrayed as tougher and smarter than her male counterparts, and answers to no one but herself. In fact she is allowed a complex enough personality that she can be both an appealing protagonist and have a simultaneous mean streak: she encourages the Mexican bandits to rape a rich white woman, claiming that because she was raped by a rich white man at age 15, she doesn’t see why this rich woman should be treated any differently. It’s a harsh moment, but it succeeds in portraying Adelita as a woman who stands alone, even though she fights for the people. And as Manuela Beyer has pointed out in Shooting (a) Woman: A Comparative Study of Gender Roles in American and Italian Western Movies (2007), the film does not punish Adelita for her confidence or her mobility. In the male-dominated world of the western, perhaps that’s the most we can hope for.

[i] Brunetta, Gian Piero. The History of Italian Cinema: A Guide to Italian Film from its Origins to the 21st Century. Princeton University Press, 2009. Pg.208

[ii] Maria del Carmen Martinez Roman was another female writer, having penned nearly ten westerns including a co-writing credit on Giulio Questi’s bizarro Django Kill! (1967) and Requiem for a Gringo (1968 – co-written with Giuliana Garavaglia who also plays Lupe in the film).

January 1, 2012

January 1, 2012

Comments

Kier-La really hits the nail on the head with this article. I always thought Patty Shepard’s role as Peg in A Man Called Noon was the hardest female character in the genre with Rosalba Neri’s Samanthan Felton’s the most ruthless character. Martine Beswick was very strong and believable in A Bullet for the general while the rest of the women he talks about were a bit down the list. Too bad the genre didn’t develop a strong female lead actress in a series of films. As well as never developing a Black leading man hero in a series, I feel they missed the boat.

7 yearss ago