IT’S A DOG’S WORLD

IT’S A DOG’S WORLD: THE FILMS OF GUALTIERO JACOPETTI

By Rodney Perkins

Rare images courtesy of Federico Caddeo (www.freakorama.net) and the Camera Obscura DVD label

—————

“A helicopter clattered overhead, a cameraman crouched in the bubble cockpit. It circled the online levitra us overturned truck, then pulled away and hovered above the three wrecked cars on the verge. Zooms for some new Jacopetti, the elegant declensions of serialized violence.”

J.G. Ballard, The Atrocity Exhibition[1]

—————-

Filmmaker Gualtiero Jacopetti died on August 19, 2011 at the age of 91. Jacopetti was a globetrotting iconoclast who consistently pushed the aesthetic boundaries of cinema. His achievements were numerous and his films still lowest propecia price remain influential. This article pays next day viagra tribute to the late director by providing a detailed survey of his career.

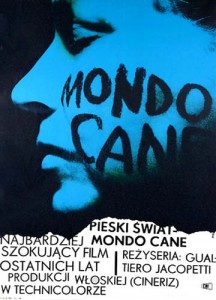

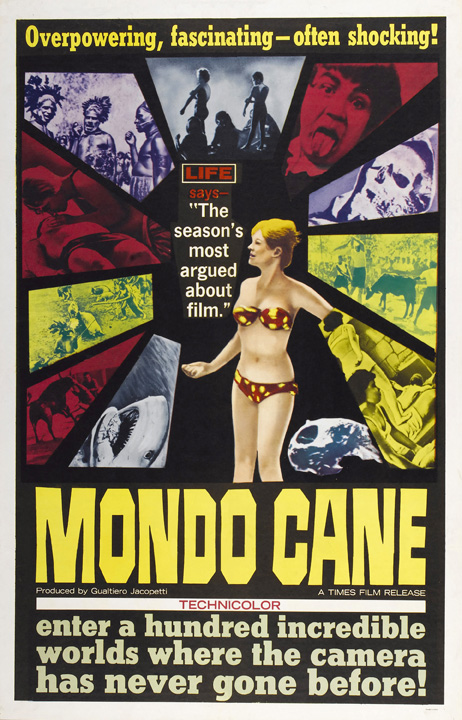

Gualtiero Jacopetti was a journalist who worked at such Italian publications such as Cronache and L’Espresso. After dabbling in newsreels and short subjects, he made the leap to documentary features. He started as a writer for Alessandro Blasetti’s films European Nights and World by Night. In 1963, Jacopetti teamed up with Paolo Cavara (who would later direct the acclaimed giallo Black Belly of the Tarantula) and a nature documentarian named Franco Prosperi to direct a film that shocked the world: Mondo Cane (It’s A Dog World).

Mondo Cane compares and contrasts “civilized” and “primitive” societies to show how all human beings—regardless of race or ethnicity—are equally weird and horrible. On one level, Mondo Cane operates as travelogue that transports viewers to picturesque locales that that they are unlikely to see. Exotic habits and rituals of strange naked people from remote islands and jungles are explored. This worldly exoticism cheap cialis india is mixed with a deep layer of cynicism. The omniscient narrator sarcastically comments on each scene pointing out the ways in which the repulsive acts of foreigners are really no different than the behavior of the Westerners. The film’s themes are accentuated through some cinematic techniques that Jacopetti used throughout his career. Specifically, Mondo Cane juxtaposes images of wildly different tonalities for ironic effect. This approach manifests itself in numerous ways:

- a sequence of humorous or light-hearted events quickly cuts to similar but shocking sequence of events;

- a seemingly humorous or light-hearted situation is slowly revealed to be part of a horrible or deviant process; or

- comedic elements are introduced into a morbid scene.

Jacopetti referred to these manipulative editing tricks as “shock cuts.”[2] In one scene, the filmmakers visit a pet cemetery. While humans mourn the loss of their animal friends, their unconcerned pets are shown urinating on the graves of their dead brethren. This comical scene abruptly ends with a cut to a huge sign in front of a Hong Kong restaurant that reads: “ROASTED DOG MEAT.” Patrons are shown eating meat dishes while caged dogs look on in torment. In the following scene, the filmmakers visit a New York restaurant where patrons buy expensive meals consisting of ants and other bugs. The viewer is then treated to close-up shots of well-dressed people scooping ants from fine china and into their mouths.

Mondo Cane boasts other elements that can be found in almost all of Jacopetti’s films. In spite of the film’s pretensions of documentary objectivity, numerous scenes are either fake or staged. The film also relies on footage of animals being mistreated or killed in order to make its points. Third, Mondo Cane uses clandestine filming techniques. A woman sued Jacopetti for allegedly using unauthorized footage her doing gym exercises in Mondo Cane.[3] Finally, the film features a lush orchestral score by Riz Ortolani, who composed music for all of Jacopetti’s films. The film’s theme song “More” received the Grammy award for “Best Instrumental Theme” in 1963. A version of the theme song by Kai Winding and Orchestra even reached the number 8 slot on Billboard’s Top 100.[4]

Mondo Cane was generally well received by critics and audiences. Variety called the film an “impressive, hard-hitting documentary feature.”[5] Bosley Crowther of the New York Times gushed with praise:

Mondo Cane was generally well received by critics and audiences. Variety called the film an “impressive, hard-hitting documentary feature.”[5] Bosley Crowther of the New York Times gushed with praise:

For there is more of a strange and grotesque nature—more that is weird, paradoxical, bizarre and reflect of the rang of man’s behavior—in this extraordinarily candid factual film than could come within an average man’s experience or be likely to be seen often on the screen.[6]

Crowther gave Mondo Cane an “honorable mention” in his list of top films for 1963.[7] Although this might seem like a minor accolade, other films on the list include Leopold Visconti’s The Leopard and Akira Kurosawa’s High and Low.[8] Others were less impressed. Pauline Kael referred to as Jacopetti and Prosperi as “documentary fakers.”[9]

Mondo Cane spawned a seemingly endless series of knock-offs that tried to replicate its successful mix of exotic locales, gross-out gags, and scandalous behavior. These films became known as—surprise!—mondo movies. These films rarely matched the cleverness and skill of the original.

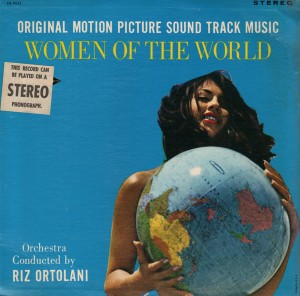

Instead of immediately cranking out a quick sequel, Jacopetti, Cavara and Prosperi followed up Mondo Cane with 1963’s Women of the World (Le Donna Nel Mondo). The film collects footage from various locations across the globe to analyze the lives of women of differing ethnicities and nationalities. Unlike Mondo Cane, which balances its salacious aspects with anthropological themes, Women of the World is more overtly perverse. Peter Ustinov’s narration lends it all an air of objectivity, but there is no escaping the notion that film is mostly focused on showing ladies of all sizes, shapes, and colors in various states of undress. Critics responded positively to the film. Variety called it a “trenchant, sarcastic, irreverent, but significant glimpse at certain aspects of the world today, with its loneliness, its hypocrisy, its justice, and injustice.”[10] The film was not without controversy. A lawsuit was filed against the U.S. and Italian distributors because the film contained footage of them wandering around a red light district in Hamburg.[11] The Israeli government gave permission to photograph female soldiers while they participated in training exercises. This permission did not extend to filming the soldiers as they showered and undressed. Israeli officials allegedly asked for the scenes to be removed from the film.[12] The scenes remain intact.

Instead of immediately cranking out a quick sequel, Jacopetti, Cavara and Prosperi followed up Mondo Cane with 1963’s Women of the World (Le Donna Nel Mondo). The film collects footage from various locations across the globe to analyze the lives of women of differing ethnicities and nationalities. Unlike Mondo Cane, which balances its salacious aspects with anthropological themes, Women of the World is more overtly perverse. Peter Ustinov’s narration lends it all an air of objectivity, but there is no escaping the notion that film is mostly focused on showing ladies of all sizes, shapes, and colors in various states of undress. Critics responded positively to the film. Variety called it a “trenchant, sarcastic, irreverent, but significant glimpse at certain aspects of the world today, with its loneliness, its hypocrisy, its justice, and injustice.”[10] The film was not without controversy. A lawsuit was filed against the U.S. and Italian distributors because the film contained footage of them wandering around a red light district in Hamburg.[11] The Israeli government gave permission to photograph female soldiers while they participated in training exercises. This permission did not extend to filming the soldiers as they showered and undressed. Israeli officials allegedly asked for the scenes to be removed from the film.[12] The scenes remain intact.

A formal sequel to Mondo Cane was released in 1963. Mondo Cane 2 (Mondo Pazzo) follows the exact same formula as the original. The film has few surprises. Although the scenarios are more varied, the film lacks the magic of the original. There are genuine moments of brilliance, though. (e.g., a row of men are slapped in the face in time with Bach’s Tocatta, a scene of people drinking multi-colored regurgitated water).

In 1964, Jacopetti and Prosperi began work on Goodbye Africa (Africa Addio). At the time, Africa was transitioning from a colonial chess set into a continent of independent nations. As the colonialists exited the country, a massive struggle for political power and natural resources ensued. Jacopetti travelled Africa with a small a film crew in order to capture the events on cameras.

Carlo Gregoretti, a journalist who once worked with Jacopetti at L’ Espresso magazine, visited the Congo write in order to write a story about the film. Upon his return to Italy, Gregoretti wrote an article in which he claimed that Jacopetti convinced Congolese mercenaries to murder three young boys on camera.[13] Italian authorities responded by bringing homicide charges.[14] The charges were eventually dropped,[15] but the pre-release turmoil did not bode well for the film’s future.

Africa Addio is a stunning film that depicts the collapse of colonialism and the rebirth of African continent. The film overflows with dead bodies. Poachers, mercenaries, political despots, assassins and native people are shown fighting for any opportunity to take these resources for themselves. People are shot point blank with pistols, ripped apart with machine guns, chopped up, lynched, and trampled to death. Rare animals like zebras, rhinos, elephants, and giraffes are slaughtered. Game preserves where elephants and gazelles once roamed harm-free are covered with miles of skeletons and horns. The mayhem is punctuated with numerous ironic shock cuts. Scenes of animals being slaughtered are juxtaposed with the executions of humans.

The critical response to Goodbye Africa was rather unkind. The New York Times review was particularly outraged:

“Far beyond any necessity of giving the viewer a sufficient idea of some of the unspeakably brutal and inhuman massacres and violences (sic) that have occurred in the explosive lands of Africa in the last few years, this film . . . piles on horror on horror until the mind reels and the stomach is revolted by the sights of mangled flesh and gore.”[16]

In 1973, Jerry Gross’ company Cinemation Industries re-released the film in the states under the name Africa: Blood and Guts. 40 minutes were shaved from the film, including all traces of political context. This tampering turned the Goodbye Africa into an incoherent barrage of mayhem and murder that does a major disservice to the original film. Jacopetti called the English version “a betrayal.”[17]

Instead of retreating to safe ground, Jacopetti and Prosperi jumped into treacherous waters with 1971’s Goodbye Uncle Tom (Addio Zio Tom). The film follows a 20th century Italian film crew that travels back in time to visit a 19th century American slave plantation. The crew documents plantation life from the perspective of both the slaves and the slave owners. Real events are depicted in naked bloody detail, including the Middle Passage by which slaves were transported from Africa to the United States. Most of Goodbye Uncle Tom was filmed in Haiti with the permission of dictator François “Papa Doc” Duvalier. Dozens, if not hundreds, of Haitians appeared as slaves in the film.

It is not surprising that public reception was completely hostile. Italian authorities seized all the prints by the end of the first day of public screenings.[18] Authorities claimed that the film was “contrary to common decency and ethical sentiments in frequent scenes of vulgar sex, by its exasperated depiction of race hatred and by tragic and bloody killings that the race struggle engenders in this spectacle.”[19] Obscenity and racial incitement charges were dropped, but Jacopetti and Prosperi still reworked the entire film.[20]

The original cut of Goodbye Uncle Tom features a fifteen-minute introduction focusing on the American racial unrest of the late 60s and early 70s. This opening sequence reveals that part of the filmmaker’s intent was to show how far blacks had progressed—or regressed—since the days of slavery. Unfortunately, most of the introduction was removed and the narration was also completely redone. The resulting film is incoherent and muddled when compared to the original version. The sarcastic narration and Riz Ortolani’s cheerful music give the film a semi-comedic tone is at odds with the horrors portrayed on screen. The spectacular finale, which is one of the best endings in cinematic history, also seems out of place. It only truly makes sense when considered together with the opening sequence.

Cannon butchered the film even further for its United States release in 1972. Their plan to ride the successful wave of American black exploitation films did not work. A.H. Weiler called it a “voyeur’s view of, not a sad good-by to, some lurid aspects of American slavery.”[21] Pauline Kael attacked Goodbye Uncle Tom with rabid fury. In an article declaiming the state of black cinema in the 1970’s, she called Farewell Uncle Tom “the most specific and rabid incitement to race war” of the time.[22] Kael deduced that the film arose from the directors’ “porno fantasies.”[23] American racist provocateur David Duke held similar views about the film albeit for entirely different reasons. He claimed that Goodbye Uncle Tom was part of a Jewish plot—the owners of Cannon were Jewish—to incite black people to riot and kill whites.[24]

Bloody and bruised by the Farewell Uncle Tom experience, Gualtiero Jacopetti and Franco Prosperi took a different approach by creating a sprawling psychedelic version of Voltaire’s Candide. 1975’s Mondo Candido is a sprawling psychedelic version of an Alejandro Jodorowsky movie. Cunégonde’s ravagement by dozens of armor-clad soldiers is visualized as a bawdy comedic skit. In a scene that predates Mel Brook’s History of the World Part 2, the Inquisition is presented as a psychedelic Busby Berkeley dance routine. Heretics dance their way into giant meat grinders while psychedelic rock music plays. Despite the bizarre visual sense, the film is very faithful to the novel. The film stays surprisingly close to the original material. Of course, scenes in which Candide and his slave companion Cacambo zip back-and-forth between modern day New York City, Northern Ireland, and Israel are significant exceptions.

Mondo Candido failed to find an audience. The partnership between Jacopetti and Prosperi, which was strained by financial disputes, dissolved. Prosperi went on to create other works, including the amazing Wild Beasts, but Jacopetti never directed another film.

AFTERMATH

Gualtiero Jacopetti stopped making films in the late 1970’s but the seeds he sowed continued to bear strange fruit. The home video boom of the 70s and 80s brought scads of obscure mondo knock-offs that either failed to take off at the box-office or were specifically tailored for home viewers. The most famous films were the Faces of Death series, but the list of nasty—and often phony—films includes: Mondo Magic, Shocking Asia, Inhumanities, Death Scenes, Traces of Death, and Death Faces IV. The film Savage World Today was even renamed Mondo Cane 3 to cash in on the craze.

Jacopetti’s influence was not limited to mockumentaries. Arguably, the ascendancy of “reality television” can be traced back to Mondo Cane. Modern genre films also owe him a great debt. Cannibal Holocaust, Blair Witch Project and other numerous films that embrace the “found-footage” formula are direct descendents of Mondo Cane. Astute filmgoers may have noticed that Nicolas Winding Refn’s fabulous Drive contains a reference to Goodbye Uncle Tom. Refn, who is an avowed student of genre films, uses Riz Ortolani’s song “My Love” to score a pivotal scene in the film. The way in which Refn matches the track to the scene’s emotional core is ingenious and reflects a keen understanding of the way the music was originally used in Goodbye Uncle Tom.

Those interested in exploring Jacopetti’s filmography should have no problem tracking down the works discussed in this article. Uncut versions of most of the films are available from Blue Underground (http://blue-underground.com/) on Region 1 DVD. Camera Obscura has recently released a two-disc Mondo Candido set on Region 2 Pal DVD.

———-

Additional thanks to David Gregory of Severin Films

[1] J.G. Ballard, The Atrocity Exhibition (San Francisco: Research Publications, 1990), 69.

[2] Nico Panigutii, “Gualtiero Jacopetti,” in Stewart Swezey, ed., Amok Journal: Sensurround Edition (San Francisco: Amok Press, 1995), 156.

[3] “Suit Raises ‘Cane’,” Variety, September 19, 1963, 2.

[4] “Billboard Hot 100,” Billboard Magazine, August 24, 1963, 28.

[5] “Mondo Cane,” Variety, January 1, 1962.

[6] “Screen: ‘Mondo Cane,’ A Series of Believe-It-or-Not Vignettes,” New York Times, April 4, 1963, L58.

[7] Bosley Crowther, “Top Films of 1963,” New York Times, December 29, 1963, X1.

[8] Id.

[9] Pauline Kael, 5001 Nights At the Movies (New York: Macmillian, 1991), 493.

[10] “La Donna Nel Mondo,” Variety, February 27, 1963, 7.

[11] “Pair Sue Embassy,” Variety, January 22, 1964, 7.

[12] “Israel Yet To Make It ‘Official’,” Variety, May 1, 1963, 2.

[13] “Director of Mondo Pix Charged With Voluntary Homicide in Rome Ct.,” Variety, April 7, 1965, 2.

[14] Id.

[15] “Dismiss ‘Africa’ Murder Charge Against 3,” Daily Variety, February 8, 1966,4.

[16] Bosley Crowther, “Screen: Two Hours of Killing Color,” New York Times, March 13, 1967, 47.

[17] Panigutii, at 145.

[18] “Cops Seize ‘Addio’ Throughout Italy,” Variety, October 23, 1963, 34.

[19] Id.

[20] Hank Werba, “Italo ‘Uncle Tom’ Beats Censor Band But Pic Withdrawn for Re-Editing,” Variety, December 16, 1971, 8.

[21] A.H. Weiler, “Screen: Farewell Uncle Tom,” New York Times, October 29, 1972, 69.

[22] Pauline Kael, “The Current Cinema: Notes on Black Movies,” New Yorker, December 2, 1972, 163.

[23] Id. at 164.

[24] David Duke, My Awakening: A Path to Racial Understanding (Mandeville: Free Spech Press, 1999), 311.

January 1, 2012

January 1, 2012

Comments