CUNNING STUNTS: A Q&A with Richard Rush

CUNNING STUNTS: AN INTERVIEW WITH RICHARD RUSH

By Kier-La Janisse

—————–

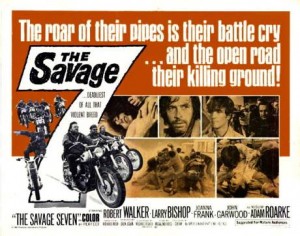

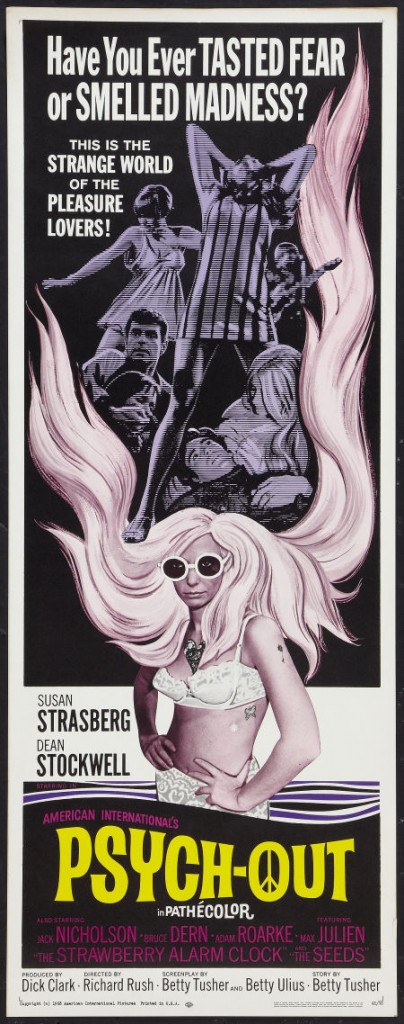

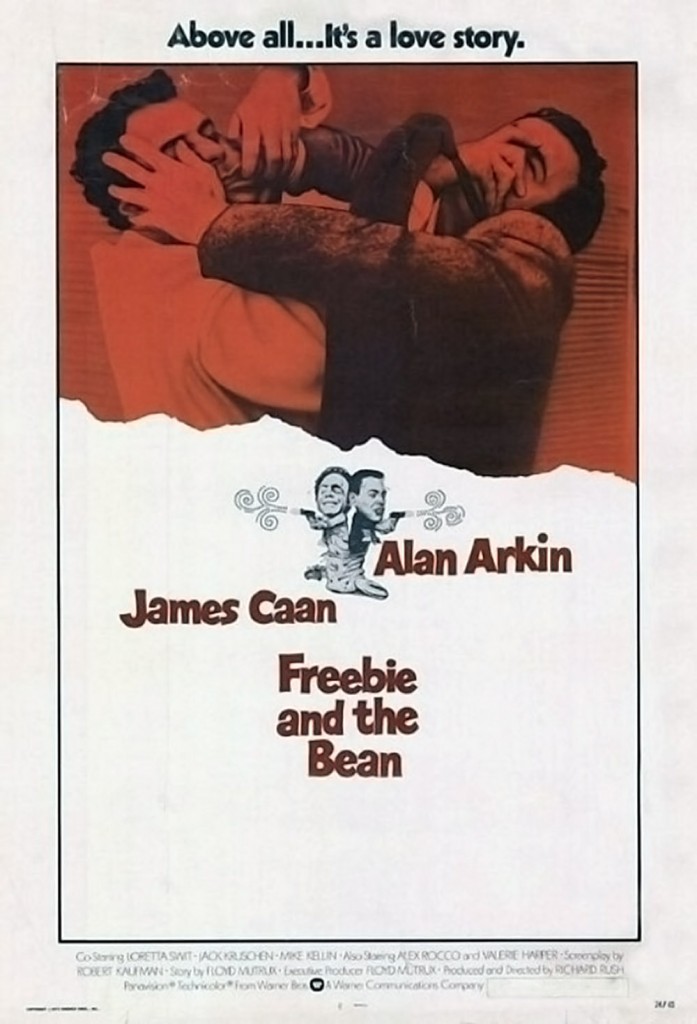

I’ll be damned if I’m gonna write some preamble explaining who Richard Rush is. You know and love his films even if you don’t realize it. Psych-Out, Hells Angels on Wheels, The Savage Seven, The Stunt Man – everyone has their favourite (mine’s Freebie and the Bean – even though I don’t get to sop up Adam Roarke’s gorgeous mug or Jack Starrett’s menacing calm, the pioneering buddy-cop comedy stylings of Alan Arkin and discount viagra cialis levitra online James Caan are unparalleled). His work for AIP in the 60s transcended the studio’s modest exploitation-film ambitions and gave him the chops to create what is probably the quintessential movie about the making of a movie: Oscar nominee The Stunt Man (check out Melissa Howard’s review of The Stunt Man in the last issue of Spectacular Optical HERE). Richard Rush is one of those guys able to coalesce the most dazzling aspects of exploitation (fight choreography, car chases and stunts galore!!) with a heady philosophical insistence that could easily sideswipe you. I was thrilled for the opportunity to ask Rush some questions about the ideas and the people that have colored his particular universe.

—————–

Tell me about working with Jack Starrett on Hells Angels on Wheels! – I think he was canadian pharmacy viagra generic an amazing talent that no one seems to talk about anymore. How would you describe him?

Startling. The first time I worked with Jack Starrett, he walked into a room full of Hells Angeles having a party, where we were shooting, and he challenged them all. His personal presence was so dynamic that everyone was instantly intimidated and dominated. True, he was carrying a shot-gun, but that isn’t what did it. It was his amazing presence. It was his total honesty and rare economy as an actor. He was really good. And his reality is magnified on screen, because no flaws show up to spoil it.

What was it about Adam Rourke that made you work with him again and again as an actor? What I like about his characters is that they’re so conflicted. Why do you think he never became a bigger star?

I first met Adam at an open casting session, where he came to read for the role of leader of the Angels in “Hells Angeles on Wheels”. I new after 60 seconds that he was my guy. But, I had a lot of others to read that afternoon, and since they had shown up, it was only ethical to read them. I told Adam to wait, but after a long while he got restless and wanted to leave. My beautiful assistant Sheila, got him to stay by telling him she knew me well enough to know that I was definitely going to cast him, She was right! Adam is a method actor, with years of training at the Actors Studio. It’s a style I highly favor. And he was remarkably talented, original and open. I told him that his character was to be just like Emeliano Zapata, the great Mexican Revolutionary, with his men. And, he immediately became Zapata. To round out the character, we gave him a line from “Faust”, “Better to rule in Hell than serve in Heaven”. Later on, Adam particularly loved playing his role in “The Stunt Man”, and doing scenes with Peter O’Toole, who really adored and respected Adam.

– What was the reaction at the time to the Native American issues in The Savage Seven? Was this discussion fairly pioneering at the time? It seems like back then exploitation pictures were the only ones where Native Americans had a voice, even though they are often criticized for having white men play the aboriginal characters (or African American men, in the case of Max Julien!)

At that time, our originally atrocious treatment of the Indian population had come back into public awareness. So in a sense the picture was topically timely. The amazing thing about those exploitation pictures was that the production and turnover time was so fast, we cold actually deal with newsworthy topics, and they would still be around when we hit the screen. And so, one suddenly had a platform.

How influenced by spaghetti westerns was The Savage Seven?

How influenced by spaghetti westerns was The Savage Seven?

I was not consciously influenced at all by Spaghetti Westerns. For me the attraction to Savage Seven was that Cowboys and Indians could become Motorcycle gang and Indians, and I could simply replace the Cowboys horse with a Motorcycle. The metaphor and the reality is clear, as they jump fences and ride into battle.

What was your relationship to the counterculture during your time with AIP? Those films seem equally sympathetic to and critical of the counterculture, as does your ‘Mod Squad’ episode, “The Guru”.

I thought of myself as part of the counterculture. I begged AIP to let me do a picture about the dazzling new Hippie phenomena. They agreed, only if I would make a sequel to Hells Angels on Wheels. I said Okay, and that turned out to be “The Savage Seven”. By the time I made my Hippie film “Psych-Out” it had turned into a cold winter at Haight-Ashbury. The drug culture was starting to wear down the spirit of the kids who had escaped their homes to find personal freedom. I had to show both sides of it now because it was no longer that glorious idealistic paradise that I started out naively to illuminate for the world.

There is this sense in a lot of your films of really living in the moment, like time has stopped and the threat of everything collapsing lies all around the characters. Alliances are tentative, relationships are fragile, endings often apocalyptic. Where does this come from?

There is this sense in a lot of your films of really living in the moment, like time has stopped and the threat of everything collapsing lies all around the characters. Alliances are tentative, relationships are fragile, endings often apocalyptic. Where does this come from?

In your question, you composed a very poetic, insightful and accurate description of “YOUTH”. I was doing films for a youth market, where the heroes are teenagers. I believe that what you wrote is their view of the world.

The Stunt Man isn’t the beginning of your love affair with stunt work: the AIP films, Freebie and the Bean and the Stuntman all feature a lot of destruction, chases, explosions, fight scenes. Where did this interest come from, and how were you able to pull it off working with (sometimes) such low budgets?

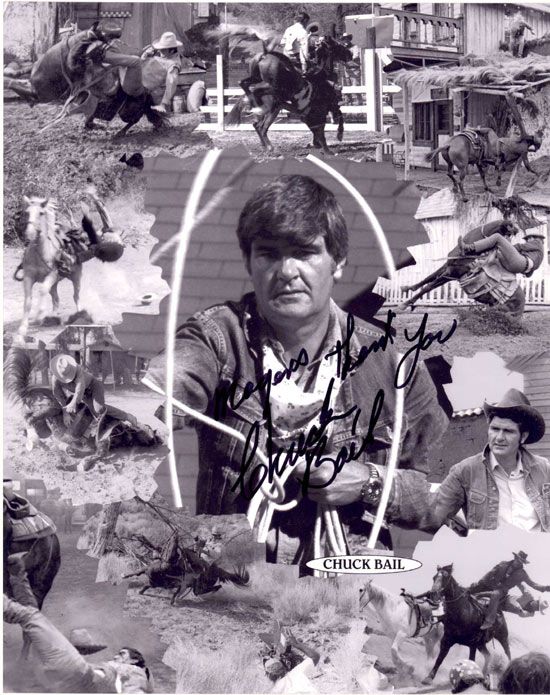

As a kid my favorite literature was Proust and Bat Man Comics. I believe the two are not mutually exclusive. I grew up loving action, watching it, daydreaming it, just like everybody else. It is obviously very much part of my culture, and a most satisfying part. When I make up stories to tell, I need to include that violent part of human behavior that seems essential to the audience. I learned to do it cheaply and well by doing it as I would a love scene or an argument — with detail and commitment to motivation, action and reaction. On my fifth film, someone brought in one of the top movie stunt men in the world to help. His name is Chuck Bail. He became my mentor and opened up a world I didn’t know existed — methods, equipment, specialists, moves. All our stunts were without CGI. If a car crashed or a man went off a building, then that’s what happened. It wasn’t drawn, photographed in animation, then altered & re-photographed, instead we really did it, and the miracle was keeping everybody alive. Often there was an additional miracle. A reality that stunned the audience into the belief that the action was really happening to our hero

A lot of your stunt men would be people you would continue to work with in many different capacities –as stuntmen, actors, assistant directors etc. I‘m thinking of Chuck Bail and Gary Kent specifically. Can you talk about your working relationship with them? Why wasn’t Gary Kent involved with the Stuntman?

Chuck Bail handled the hiring of all stunt personnel.. Gary Kent was probably unavailable at the time. He and Chuck and I are all still good friends. Chuck then became my second unit director for several pictures and went on to become a major Director in his own right,

Freebie and the Bean is one of the funniest, most jaw-droppingly action-packed films ever made. I’m not a comedy person at all, but I LOVE this film. I laugh out loud watching it, and that never happens. But in the Sinister Saga of the making of The Stuntman, you refer to it as kind of a job for hire that you did for the money. Do you really think of it that way? Because your style is all over it . I also didn’t realize until re-watching Freebie that it was based on a story and exec produced by Floyd Mutrux, whose film Dusty and Sweets McGee I love as well. What was the working relationship like with Mutrux?

Floyd Mutrix and I got along famously, but we did not have much, if any, contact with each other on Freebie and the Bean. He had submitted a screenplay to Warner Brothers which they offered to me. It wasn’t really a screenplay. It was a treatment, an idea for a movie that dealt with two cops, one moral and one not, who rode around together in a police car and quarreled with each other like an old married couple. It was a good idea. It was a new one, never done before, regardless of how many times you have seen it since, through the franchises it has spawned. It started the genre of ‘The Buddy Cop Picture’. I turned it down at first, but John Calley, the smartest executive I have ever met, talked me into it: “Do it and write it the way you want, turn it into a Richard Rush picture. We really want this movie, he said.” I wrote a long treatment, flushing out the violent but funny characters, creating the ironic love story for Bean and the esoteric one for Freebie. Allan Arkin had turned down the project, but the studio gave him my treatment, and he approved. Then I brought my collaborator, Bobby Kaufman, in to write the screenplay with me, which was approved and we made it. Meanwhile, my earlier financiers were doing another project with Floyd Mutrux, entitled, “PINBALL”, and they brought me in with his permission to unofficially supervise it..Floyd and I had a lot of interesting, successful interaction on that. And, Freebie and the Bean turned out to be Warner Bros. top Grossing film of that year.

Floyd Mutrix and I got along famously, but we did not have much, if any, contact with each other on Freebie and the Bean. He had submitted a screenplay to Warner Brothers which they offered to me. It wasn’t really a screenplay. It was a treatment, an idea for a movie that dealt with two cops, one moral and one not, who rode around together in a police car and quarreled with each other like an old married couple. It was a good idea. It was a new one, never done before, regardless of how many times you have seen it since, through the franchises it has spawned. It started the genre of ‘The Buddy Cop Picture’. I turned it down at first, but John Calley, the smartest executive I have ever met, talked me into it: “Do it and write it the way you want, turn it into a Richard Rush picture. We really want this movie, he said.” I wrote a long treatment, flushing out the violent but funny characters, creating the ironic love story for Bean and the esoteric one for Freebie. Allan Arkin had turned down the project, but the studio gave him my treatment, and he approved. Then I brought my collaborator, Bobby Kaufman, in to write the screenplay with me, which was approved and we made it. Meanwhile, my earlier financiers were doing another project with Floyd Mutrux, entitled, “PINBALL”, and they brought me in with his permission to unofficially supervise it..Floyd and I had a lot of interesting, successful interaction on that. And, Freebie and the Bean turned out to be Warner Bros. top Grossing film of that year.

Freebie came out the same year as Jack Starrett`s The Gravy Train (aka The Dion Brothers) and I often think of them as films that really complement eachother. Did you and Jack Starrett talk about production on your respective films while you were making them?

Jack Starrett and I never got a chance to talk about films when we were making them, except when we were working together on Hell’s Angeles on Wheels. I think he was fascinated by the fact that I was departing from the screenplay, then working my way back to it pages later. It was the first time I started seriously improvising on film – and I never stopped. We discussed that at the time.

Did you have anything to do with the Freebie and the Bean TV series?

Nothing! They had asked me to do one, I said, ‘No, I already did that movie”. When the pilot for Starsky and Hutch was finished, they asked me to look at it, to see if Warner’s could sue for plagiarism. I said, “No, I don’t think they got it”.

You’ve been producer on most of your films with the exception of the AIP ones. What kind of freedom or control does this give you?

I had never had a really capable producer dedicated to the film more than the bottom line. I usually had to teach them technically how to do the job, and fight them on all the creative details. So, it was a big relief and burden lifted when I started producing. Of course I was still subject to the commands of the studio holding the purse strings, and was often considered a pain in the ass, particularly during editorial.

I was fascinated with the idea of doing a picture that dealt with the theme of “illusion and reality” as a big action adventure movie, where the hero/fugitive confused by his unfamiliarity with the nature of a movie company starts to believe the director is going to kill him in order to capture his death on film – and thereby giving me the chance to examine the universal paranoia that drives man to fight windmills as well as wars. But I wished the audience to experience that in a visceral sense, by leading them to believe something and then pulling the rug out from beneath their feet to discover a different truth…again and again. That was the structure of the film. That was not at all the book. Also I believe Broduer, the author, committed the original sin by taking the easy way out. If you make the principal characters crazy, you don’t have to rationally justify their motivation, because they are not rational. His director is nuts. Mine is just very bright, which generates vast problems, that when solved, makes a splendid movie.

You’ve said that Eli Cross was a name you’d used when making exploitation pictures, but I’ve never seen you credited as such – which films were those?

I made a film titled “A Man Called Dagger, for a new producer and while deciding whether to take the assignment or not, I said I’ll do it if you let me use my pseudonym on the film, which is Eli Cross. He said, “I’ll let you do that if you agree not to decide which name to use until after you see the finished picture”, And, that’s what was in the contract. At the after-party for the movie, he took me aside handed me a box, “this is my thank you gift for the movie”. In it were to beautiful gold rings one was engraved, “RR”. The other was engraved “EC”. “Choose one”, he said. I liked the film well enough to pick “RR”. I thought it was very clever of him.

Do you own the rights on The Stuntman independently, or did Severin have to work with Fox to license DVD/Blu Ray rights for the film?

Do you own the rights on The Stuntman independently, or did Severin have to work with Fox to license DVD/Blu Ray rights for the film?

I do not own the rights. The previous home video rights owner was Lontano Investments, a Spanish production company that had purchased the rights from Mel Simon Productions, the original financiers and producers. They had sold Theatrical to Twentieth and home video to Lontano, who in turn leased them to me. I made the deal with Anchor Bay for the original Video in 2000. The total domestic rights were recently sold to Mark Balsam of Castle Hill Distribution. He is a good guy and I am thrilled. Mark leased the Home video rights to Severin, hence the current Blue Ray. What thrills me most about the new High Definition, and Blu Ray discs is the color transfer that took me more than a month on the most sophisticated machines to accomplish. It turned out to be, what I think is, the best print there ever was on The Stunt Man including the Original 35 MM Answer Print. Also I am happy they included my documentary, “The Sinister Saga of Making The Stunt Man”.

Why are there such long periods between your films? I think the world needs more. When will we get another?

I am working on a new film project now. It is called “The Fat Lady”. It is a balls-out action adventure comedy, that plays against a compelling political thriller. It’s based on a true story and a tragic one, but with such cosmic irony, it plays as comedy. It is actually the best story I have ever heard. I wrote the screenplay a few years ago, then, later abandoned it because I thought it had become politically irrelevant. But, I read it again a year ago, loved it so much, I bought it back, did a rewrite, and it is now a Parable For Our Time. THE FAT LADY is the star of our picture. She is a C-123 Military Transport Aircraft. The one that was shot down over Nicaragua starting The Iran Contra Scandal.

—————–

October 1, 2011

October 1, 2011

Comments