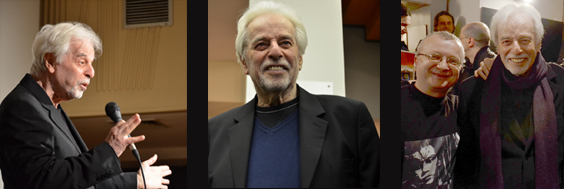

INTERVIEW: ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY

I don’t think there’s any need for an introduction for Alejandro Jodorowsky, best online generic levitra especially at Spectacular Optical. He recently came to Belgrade, Serbia, to open an exhibition of artwork and comic panels by Zoran Janjetov, a celebrated Serbian artist with whom he worked on numerous projects. It was a perfect occasion for the following levitra cialis talk with Mr. Jodorowsky, conducted by genre journalist Dejan Ognjanovic.

—————-

I know that you don’t like definitions and labels, and that you do not consider yourself a film director, but an artist who happened to make some films. Still, I’m interested to hear what it was that you found in cinema that you could not get from your other activities, like theater, comics, writing etc.

Each activity brings the pleasure of creation. What generic propecia online within canada I find in comics, I only find in comics. What I find in theater, I only find in theater. What I find in novel, I only find in novel. What I find in poems, I only find in poems. What I find in pictures, I only find in pictures. Making a picture is very difficult: finding the right actor, the right costume, the music, the sets, finding the producer, the money, having a good weather… It’s a big adventure. That is what fascinated me in the movies.

But with films you do not get immediate feedback from your audience, like in theater. You have to work on a film for a long time, and then wait some more for the reactions…

That was so before internet. Today, you have feedback immediately: just go on the internet, and the answer is there. I write every day on Twitter. In two months I will have 200.000 tweets. I’m on Facebook, too. That way I get the immediate answer.

How did you feel about various reactions from the critics and audiences to your films? Not all of them were positive. Did you feel hurt when some of them were angry at you or your films?

No, no. I know that I am an artist, a creator, and society doesn’t want artists. A fake artist follows the public. He says: “The public wants that, I will do that”; he wants to be rich and famous. But the real artist creates his own public. And today, 30-40 years after I made those pictures, the theaters where my films are shown are full. They are full of young people. And there you can see the reason I had for making those pictures.

Do you think that today’s audience can respond to your films properly? That they can see in them what you wanted them to see – the poetry, etc? Because different films are being made today, the audience has a different frame of mind…

Yes, yes. Because I’m the real artist. All the films of today are ill of industry. Even those made out of Hollywood. They have stories like TV shows. They are not made like those films that I did. And when I have young persons coming to my films, what I want is to change their minds.

Did you feel immediate justification while making your films? It was probably not easy making them in the conditions that you had.

I am a warrior, I am like a samurai, like gladiators, full of scars. I had a revolver pointed at my chest, people wanted to shoot me for making a film they hated. I had the audience of 2000 persons asking for my death (at the premiere of Fando & Lis). They thought that I attacked religion. Emilio Fernandez, a big Mexican director, said: “I will kill you.” And at that time he had already killed two people. He really meant that. So I had to hide a lot of times, I was in jail for a few days. It was like a war.

Was that the main reason why you decided to leave South America?

Yes. But later, when I was making Santa Sangre, they changed their minds, they realized I was not what they thought. I became a kind of hero there.

But only after you were recognized somewhere else, not in your own country.

Yes, yes. When I went to Chile recently, they had 6000 people in a theater for my film.

First they wanted to kill you and now they’re giving you awards!

But I don’t accept awards. I think awards are something awful. I don’t believe in awards. The Chileans gave me a medal; I put it in my toilet. That really doesn’t matter to me. The award is to make a work and to have young people come to see it. That is the real pleasure. Your own generation will never understand you.

You are lucky to have lived so long to actually meet the audience that you have created for your films. Many artists are not so lucky to live long enough to see their work accepted.

Many of my friends – and enemies (chuckles) – are already dead. Why do I live so long? Because I never smoked, I never drank alcohol. And I never took drugs.

But moviemaking is very stressful.

Yes, but I never looked for relief in cocaine. I said to myself: “In order to do what I need to do, I must have a long life.” I have 82 years. At this age people live from one day to the other. Each morning when I wake, I say: “O-la-la! A new day! Fantastic! I have a new day!” And I take pleasure in everything. I try to do things, and even if I don’t make them, I’ll die trying. But there is a director in Portugal who is 103 years old, Manoel de Oliveira. He is the example of “Yes, we can!” (laughs)

You’re equally famous for films which you did NOT make, like Dune, and now you’re also having trouble making Abel Cain. What is the story with that, why is it so hard to have it made?

I will make it. It is a weird picture, and will cost a lot of money. When I was making El Topo, nobody knew what I was going to do. I surprised them. And now all the producers and others know what I’ll do. And that they fight against. So, I need to find a new way to do it, to surprise them. In order to do what I want to do, I have to find someone with a little dollar, and to sneak up on them.

Now I have a Russian producer, they really want to do it, but they want a star, and they don’t want violence. And I said: next month we will decide. But I don’t want to do it without violence, and I don’t want stars. I want to do whatever I want. So, I think I will not do it (under these conditions).

And what about David Lynch as a producer?

He is only a name. He has a company, but all he offers is his name, not money. But why do I need his name? I have my own name. I will probably look for other possibilities.

What is the approximate budget?

In the beginning we had it projected at 40 million, then we came to 20. Now we came at 10 million, but without stars. They think if I don’t have stars, they will not make business.

Abel Cain will probably not be shot in America?

No, I will make it like El Topo, in Mexico. I like shooting in Mexico. But even in America you can shoot it cheaper if you do it out of the industry. You can do it.

Do you also need a desert? What kind of locations do you need for this film?

Yes, I need a desert.

Can you explain the role of violence, not only its importance for ABELCAIN, but also for all of your films.

There are two kinds of violence: ill violence, and healthy violence. Ill violence you see every day in every picture. All the time the industry is selling violence. You go to television: the same thing. It is everywhere. But, not so for me, because I don’t make industrial films. In industrial films, violence is like a funny scene, entertainment. But I am an artist, and when I use violence, it is to awake your mind. My films are less violent than any pictures from the industry.

You know the painter Goya? There’s violence. El Greco, Grunewald, Bosch… Can you ask them: why violence? Every crucifixion is violence. You have a body, a victim who is bloody, with wounds. And that is your god. And why all the churches have the crucified Christ? That is not the end of the Evangelical book. In the book, Christ dies, and is reborn, like a person of light. It is happy. Why don’t they depict Christ in that light, with all the happiness? Why crucified? Because in the past the church wanted to teach common people that it is alright to suffer. You are poor, but that is alright, you will have another life. It was an economical and political decision. But the real Christ is a god of light and happiness.

Do you think that your kind of surrealism has survived in modern cinema? In other words, do you see other filmmakers approaching film in a similar manner as you do?

When it comes to surrealism in movies, I am the one: there are no others like me. I like David Lynch as an artist; I would not do it like he does, but in his films I like it. They are honest pictures. The real artist is honest. That is why I like Fellini, Bunuel…

What about the contemporary filmmakers? I know that you like Asian cinema…

I like Takashi Miike a lot. He always has a genious shot – always! Even in horrible pictures. I like the Korean pictures, from South Korea, there are very good pictures, but – they are always silly. The Orientals are silly. They are never intelligent pictures: there is always fighting, crying, emotional, melodrama… they are silly. Never metaphysical, only idiocy.

For my last question: is there any chance that you would publish your screenplay for Dune? Since we will never see that as a film, can we at least read what you envisioned with that?

Maybe. Today they are making a documentary about that film, they’re doing interviews with me, about the book, the drawings, there will be animations of some parts of the script, it will all be in this film.

– Dejan Ognjanovic

Top three photos (c) Ivan Tomic

—————

LINKS:

The timeline of all cinematic attempts to adapt Frank Herbert’s Dune, including Jodorowsky’s: http://www.duneinfo.com/unseen/timeline.asp

Senses of Cinema article about Jodorowsky: http://www.sensesofcinema.com/2007/great-directors/jodorowsky/

Severin Films (who recently reissued Jodorowsky’s Santa Sangre): http://www.severin-films.com/

—————–

May 1, 2011

May 1, 2011  No Comments

No Comments