HOT DOCS 2015: THE CREEPING GARDEN

With Jasper Sharp and Tim Grabham’s fantastical slime moulds documentary THE CREEPING GARDEN making its Toronto debut at Hot Docs tonight (April 24, 2015) at 9:45pm (details + tix HERE), we’re taking the opportunity to re-post our interview with the directors from the Fantasia Festival in August 2014.

PLUS! if you like the film be sure to check out THE CREEPING GARDEN tie-in book, being released by Alchimia Press (an off-shoot of FAB Press) in July 2015!

++++

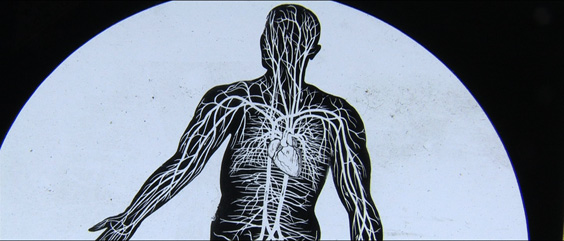

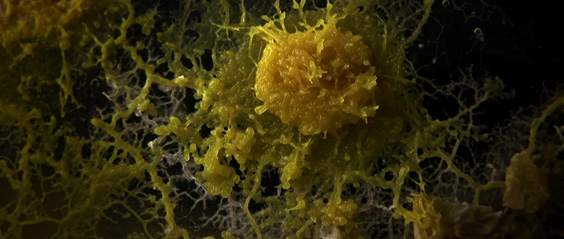

One of the strangest films to feature in this year’s Fantasia lineup was undoubtedly Jasper Sharp and Tim Grabham’s documentary on…slime moulds. One can be forgiven for not knowing what a slime mould is – it is in fact a type of mutating, gelatinous organism that reproduces through spores and lives in areas rife with dead plant material – but the strange organism has never been widely researched, and has often been mis-categorized as a type of fungi. Still, the slime mould does have its champions, and in their hypnotic film THE CREEPING GARDEN, Sharp and Grabham speak with a small but enthusiastic cadre of scientists, archivists and artists who illustrate the diverse abilities of a slime mould, which can do all manner of unexpected things – from playing music to building robots.

With a complementary blend of psychedelic visuals, humour and an eerie analogue soundscape (by renowned musician and producer Jim O’Rourke), the film at times recalls the documentaries of biologist Jean Painlevé (1902-1989)*, which themselves were early examples of educational subjects wrapped in the alluring garb of science-fiction adventures. In this light – as well as the obvious mental association with cold war-era sci-fi - it makes perfect sense that THE CREEPING GARDEN would have canada cialis no prescription its first unveiling at a genre film festival.

While this is their first film project as a duo, Grabham is a film editor by trade and Sharp a respected genre film scholar, co-editor of the seminal web journal Midnight Eye and author the acclaimed FAB Press tome on Japanese Pinku films, BEHIND THE PINK CURTAIN. I sat down with the directors for a chat about their fascinating doc on the eve of its world premiere.

Spectacular Optical: Where did your interest in slime moulds come from, and what drew you to that subject matter for a film?

Jasper Sharp: Well as one of my hobbies I was trying to learn more about fungi, foraging and mycology – mushroom-spotting, basically. I like wandering around the woods looking for edible stuff, and taking photos of mushrooms. It’s a weird subculture. And I’ve got all these guides, slime moulds are usually listed in the guides because they usually fall under the category of mushrooms; mycologists are interested in them even though they’re not technically fungi. So I didn’t really know much about them, and I think I was scouring around drunk on the internet one night and saw best discount cialis the stuff about them running through mazes. And I thought, “oh there’s a lot more to slime moulds,” so I looked on ebay for a book about slime moulds and came up with Andy Adamatzky’s book, his first book called Physarum Computing, and it was all about how to build a buy vardenafil levitra computer out of slime moulds. And I thought, “This is mad!”

I met Tim when I was doing ZIPANGU Fest, my indie Japanese festival, because we showed his film KanZeOn a couple years back. It’s a film I really love, a documentary about music and order cheapest propecia online spirituality in Japan. As a documentary I loved it because it wasn’t all talking heads, it was very stylized and he managed to convey a lot of its essence through images and sound. So when we were setting up the premiere for that, I asked what else he had lined up and said “here’s a good idea for a documentary!” And Tim said “yeah that sounds really good!”

SO (to Jasper): So how did you pitch it to him?

JS: Well it was quite a hard pitch! It took about a year to work out whether it was feasible to turn something that was kind of…globular…(laughs)

Tim Grabham: Well it’s like how are you going to make a feature film about this ‘thing’, there needs to be a little bit more to it than just the slime mould itself. But after about a year working it out we realized that the levitra cialis people who study it are very interesting as well, and you need that human element.

JS: the idea that someone was trying to make a computer out of it, then there was the robot controller, then there was Heather [Barnett] doing her art, so we were looking around going wow, there’s almost a subculture – all these people were aware of eachother but not really working together. For one of her installations in Rotterdam, the slime mould simulation, she was actually using the software developed by Jeff Jones, the programmer. But to most people, they would never know that there was this research going on, it’s really at the fringe edges of science. So I wanted to know what kind of crazy people would try and…build a robot out of slime moulds!

SP: Yeah, when you’re interviewing the people who work in the archives with all the drawers and everything, you can tell they never get to talk about this stuff much!

JS: As far as I can tell there are three major archives of slime molds in the UK – Kew Gardens is the big one, the Natural History Museum – but they wanted way too much money, they weren’t really cooperative with us – and then there’s this botanical institute in South London about two stops away from my house and I hadn’t heard of this place until after we’d done the film. It’s one of these sort of dusty old museums that nobody went into at all, and they showed me their slime mould collection and said “I don’t think anyone has ever looked at this at all.”

SO: I love how it begins and ends with that framing story of the TV newscast, you know “people in Texas have found a blob in their backyard!” and then you go into all these chapters of all the crazy things they can do, and then at the end it’s like, “Oh they found out it’s just a fungus.”

JS: I think it was a National Geographic from 1980 which mentioned this instance in Texas where these blobs started appearing all over basements and gardens. We found all the news clippings, it was funny. People thought it was taking over the whole planet, because people would pour water or petrol on them and they would just divide and multiply and pop up in other places.

SO: Do you think the sci-fi writers of the 50s had heard of slime moulds or was it a coincidence? Because the way they behave really is science fiction-y. It really does make you think they’re up to something.

TG: There’s a slight misconception online, in which THE BLOB is seen to be influenced by slime moulds, but that’s not entirely true. As far as we could work out, there’s another thing called star jelly which actually resembles the blob of the ’50s film a lot more than an actual slime mould. So I think there’s a slight mixup there in terms of what it was that actually inspired THE BLOB film. But then again a slime mould behaves more like the thing that you see in the film because it moves around and absorbs things. So I guess it might be a hybrid. But as it is with the internet, as soon as you find it in one place it kind of spreads network-like, which is a great analogy for the whole way that a slime mould works. It’s a very analogous organism, which we found more and more as we made the film. And in the end it became kind of a fabric for the way we approached and structured the film as well, like an expanding, tendril-like network of filmmaking.

SO: Is there anything like medicines that can be made from them? Are they being studied for this purpose at all?

JS: Well I think that’s one of the reasons a lot of money isn’t being put into their research, because they don’t seem to have any immediate use in the way that, say, mushrooms are used for degrading plant matter and turning it into soil, but for slime moulds, all everyone’s been doing is finding different species and categorizing them, but not really finding any purpose for them – but then again, we’re probably not much use to slime moulds either!

SO: How did you get Jim O’Rourke on board for the score?

JS: Well that’s connected to BEHIND THE PINK CURTAIN and MIDNIGHT EYE. Jim – you know him from Sonic Youth and everything – but he is a big Japanese film fan.

SO: He lives in Japan, doesn’t he?

JS: He literally moved there just as I came back from living in Tokyo, but he got in touch with me years before that because he liked MIDNIGHT EYE and we kept up this rapport because we have very similar tastes in Japanese films. After I wrote BEHIND THE PINK CURTAIN he ended up working on Koji Wakamatsu’s UNITED RED ARMY. There was always that common ground in terms of film. But at some point I told him about the film and he thought it sounded cool, so about a month later I asked if he’s be interested in doing the music and he said yeah.

SO: Did he do it after the film was completed?

JS: Sort of parallel with it, but I don’t think he watched any of the footage so much. He does lots of soundtrack work but I don’t know completely how he works, whether he just likes to work completely independent of the directors. It wasn’t a close collaboration. But I think he’s really savvy. We were editing and he would just deliver a new batch of sounds and we would build the movie around that. The other thing is he works purely analog as well, so he was talking about taking out all these ’70s synths, and what I think is nice is that it’s weird and pulsating, but still analog and organic, rather than feeling synthetic.

SO: Did he use any slime moulds in the creation of the music?

TG: No, I don’t think so but Eduardo did, who is the guy in the film, you see the sonification that is all derived from the oscillations of these things. It’s like using a kind of midi-controller.

SO: How did the breakdown of labour work between you two?

TG: Jasper and I had very particular roles in the film, I’m an editor and filmmaker as my job, so I was behind the camera and shot the majority of the film.

JS: I didn’t touch the camera or the editing desk…

TG: You were quite fearful of the technology, weren’t you?

JS: Yeah, I knew what I wanted, and we both had a very clear vision of how we wanted the film to look. I did the questions, the research, the interviews.

TG: I mean you have to figure out where your frame of reference is in terms of the aesthetic, and there were ‘70s films like PHASE 4 and THE ANDROMEDA STRAIN that were massively influential, but then you’ve got to practically put that into play. A lot of the cameras we used were borrowed, they weren’t new DSLR cameras, which are actually a bit of a disadvantage sometimes – when you use DSLR cameras for a documentary they’re a pain in the neck because they’ve got such a shallow depth of field. So we were using older video cameras which were great because following people around and keeping it locked is a lot easier. And it doesn’t look like everything else, so it had that slight throwback feel. Equally with the time lapses, they didn’t look like the current aesthetic.

SO: I was going to ask about the time lapse, has time lapse photography changed a lot since the time of Percy Smith who had made a film about slime moulds in the 1930s?

TG: Well there’s two things to that question, what we were doing wasn’t strictly speaking time lapse, because that would be taking a frame, waiting a period of time and taking another frame. Whereas what we were doing was recording over a period of time and then speeding the footage up. But in essence, yeah, it’s the same thing.

SO: Were the time lapse shots done indoors in a controlled environment?

TG: Yeah they were all done in my studio.

JS: Well, not all of them, we had the pulsating ones on the trees, and that was done in natural light.

TG: Right, which was very complex, because light changes all the time.

SO: So did you have cameras that you left alone in the woods?

TG: No. Not in London, we’re not going to leave cameras out!

SO: So then how long would you have to stay in the woods in order to see it moving?

TG: Well the best cameras for doing time-lapse are tape based, and you’ve got maximum one hour on a tape. And that’s not very much – if you were doing a mushroom or a flower, you’d get nothing. But these things move really quickly, so you can actually get a really great sense of their dynamic in just an hour. Not all of them move as quickly over an hour as the yellow one – the Physarum – which is predominantly why we used that one so much in the film; it’s quite active.

SO: I thought it was really interesting to have the woman who ties all the people together to get them to act as a unified network of slime moulds, with no inherent leader to the group.

TG: If there’s anything that it sort of demonstrates, it’s that it’s really hard to lose your individuality and become a mass, without dominating in any way. Inherently some people dominate and some people are subservient and you can’t really get rid of that, but then we’re human beings, that’s sort of built into our makeup, isn’t it?

*****

THE CREEPING GARDEN plays at Hot Docs on Friday April 24th at 9:45pm (Scotiabank)/ Saturday April 25 at 2:30pm (Scotiabank) and Saturday May 2 at 8:45pm (TIFF Bell Lightbox). Tickets HERE.

Official website: http://www.creepinggarden.com/

April 24, 2015

April 24, 2015  No Comments

No Comments