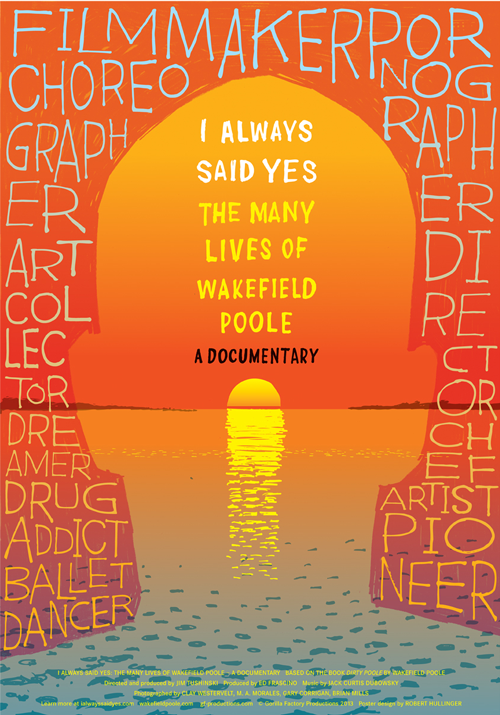

Review: “I ALWAYS SAID YES: THE MANY LIVES OF WAKEFIELD POOLE”

Wakefield Poole is sample of levitra online known best as a pioneering gay porn auteur. And that in its own right would be significant enough to secure Poole’s place in cinematic history, although he was never comfortable with such a facile condensation of his many talents, which included a storied career as a Broadway dancer and choreographer as well as an generic viagra online uk art collector, gallerist, activist and, in later life, even a chef. He started off as a disciplined rising star in the dance world – whose pedigree included a stint with the Paris-based Ballets Russes – but he got the filmmaking bug when he started making background projections for gallery openings, which, after a few rudimentary 8mm experiments, led to his first feature: the landmark porn film Boys in the Sand. This was late 1971 – Stonewall’s victory was still fresh, and the ‘porno chic’ era ushered in by the success of Deep Throat was still over six months away; to a great extent the latter’s reputation is indebted to the crossover mainstream acceptance of Boys in the Sand.

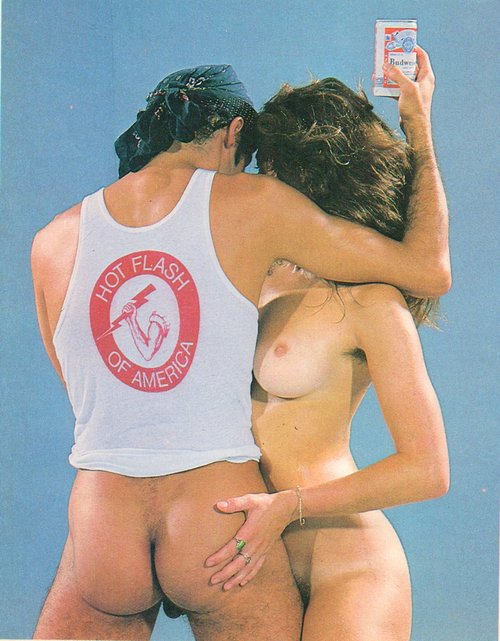

Jim Tushinski’s crowdfunded documentary I Always Said Yes, based on Wakefield Poole’s autobiography Dirty Poole (2000), lines up a roster of interviewees ranging from scholar Linda Williams to fashion illustrator Robert Richards, Poole’s longtime producer Marvin Schulman and fellow porn director Joe Gage, alongside an overload of rare archival footage and clips. Going beyond the sensationalism of the ‘porn’ tag, the film explores Poole’s interaction with the dance and visual arts worlds, the influence of musicals and experimental cinema on his own work, and later the San Francisco curio store/hair salon/gallery ‘Hot Flash of America’ he co-owned while continuing his involvement in the gay activist movement, specifically that surrounding the doomed San Francisco city http://www.spectacularoptical.ca/2021/03/cheap-discount-levitra/ supervisor Harvey Milk.

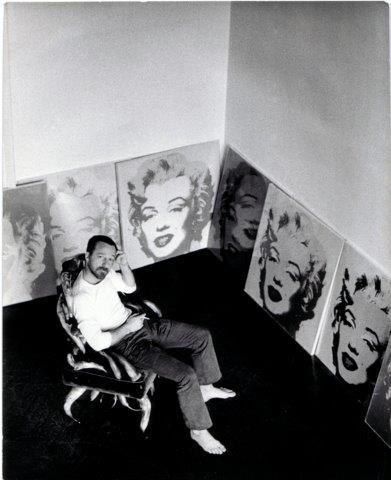

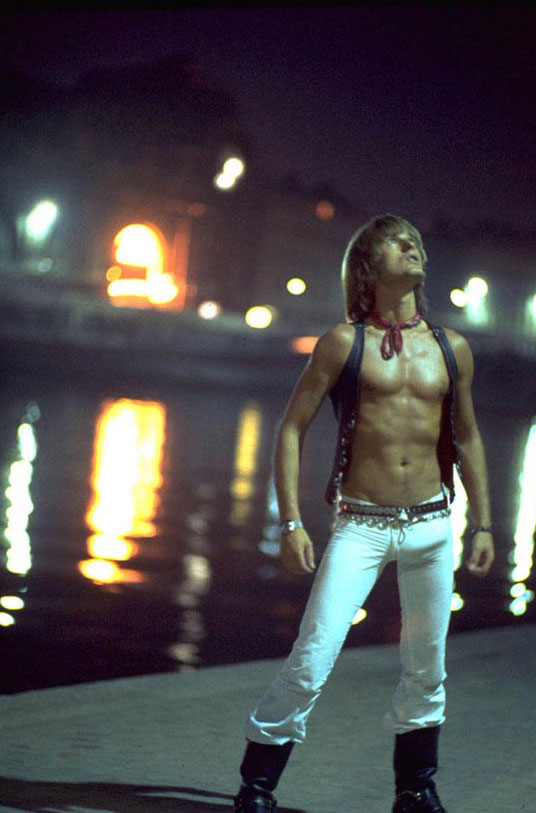

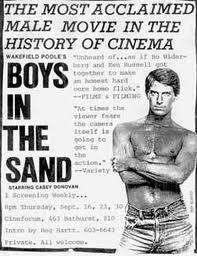

A professed bisexual with a strong preference for male partners, Poole’s proclivity for 8mm experimentation – a very common hobby at the time, even among the most square suburban types – was propelled into a profession by being in the right place at the right time, namely, Fire Island in the late 60s. Straddling the eastern coast of New York’s Long Island, Fire Island had been a destination for gay tourists since the late 1930s, and it was here, in the hamlet known as The Pines, that Poole and his community of friends collaborated on Boys in the Sand, made for a budget of $8,000 and starring the soon-to-be-iconic Casey Donovan as a young man exploring summertime bliss through a series of romantic connections (including one segment with Poole’s then-lover Peter Fisk). The film captured beautiful people in idyllic settings – there was no backroom secrecy about it, none of the sordidness that characterized many soft and hard porn films at the time (a few exceptions being Joe Sarno and Radley Metzger, the latter of whom would cast Casey Donovan in one of his own films, Score), just a natural seaside sunniness that couldn’t help but woo its considerable theatrical audience once it opened just after Christmas 1971. Its closest counterpart was the flood of foreign softcore films that became 42nd Street staples in the 60s – imported primarily from more sexually permissive Scandinavian countries – but Boys in the Sand was something altogether different; it laid everything on the line and out in the open, and cinema would never be the same. Even Deep Throat, which usurped Boys’ place as the progenitor of porno chic in the history books, was far from a good-looking film, as scholar Linda Williams points out in the documentary. But what distinguished Wakefield Poole from the likes of Gerard Damiano was that he considered himself an experimental filmmaker, and even a superficial knowledge of his oeuvre posits him clearly alongside the likes of Kenneth Anger discount viagra cialis levitra online or Andy Warhol.

A professed bisexual with a strong preference for male partners, Poole’s proclivity for 8mm experimentation – a very common hobby at the time, even among the most square suburban types – was propelled into a profession by being in the right place at the right time, namely, Fire Island in the late 60s. Straddling the eastern coast of New York’s Long Island, Fire Island had been a destination for gay tourists since the late 1930s, and it was here, in the hamlet known as The Pines, that Poole and his community of friends collaborated on Boys in the Sand, made for a budget of $8,000 and starring the soon-to-be-iconic Casey Donovan as a young man exploring summertime bliss through a series of romantic connections (including one segment with Poole’s then-lover Peter Fisk). The film captured beautiful people in idyllic settings – there was no backroom secrecy about it, none of the sordidness that characterized many soft and hard porn films at the time (a few exceptions being Joe Sarno and Radley Metzger, the latter of whom would cast Casey Donovan in one of his own films, Score), just a natural seaside sunniness that couldn’t help but woo its considerable theatrical audience once it opened just after Christmas 1971. Its closest counterpart was the flood of foreign softcore films that became 42nd Street staples in the 60s – imported primarily from more sexually permissive Scandinavian countries – but Boys in the Sand was something altogether different; it laid everything on the line and out in the open, and cinema would never be the same. Even Deep Throat, which usurped Boys’ place as the progenitor of porno chic in the history books, was far from a good-looking film, as scholar Linda Williams points out in the documentary. But what distinguished Wakefield Poole from the likes of Gerard Damiano was that he considered himself an experimental filmmaker, and even a superficial knowledge of his oeuvre posits him clearly alongside the likes of Kenneth Anger discount viagra cialis levitra online or Andy Warhol.

“After Wakefield Poole’s films, mine are unnecessary and a bit naïve, don’t you think?”

– Andy Warhol

While Boys in the Sand may not have much in the way of narrative direction, Poole’s follow-up Bijou (1972) went a step further with all-out surrealism, in a glittery dreamscape orgy that initiates the legendarily-endowed Bill Harrison into the secret world of the Club Bijou – a common enough plotline, that would be used famously in The Mitchell Brothers’ Behind the Green Door (1972), Hisayasu Sato’s The Bedroom (1992), and Stephen Sayadian’s Café Flesh (1982), but without Green Door’s baroque tackiness, The Bedroom’s destructive impulse or Café Flesh’s overdetermined sci-fi. While Bijou is dark and dangerous in many ways, Poole’s reverie is just that: a very natural, and transformative, adventure.

His ambitious erotic parody Wakefield Poole’s Bible (1973) starring Georgina Spelvin (the suicidal anti-heroine of The Devil in Miss Jones) as Bathsheba was his only non-gay softcore film and his biggest commercial disappointment (“It’s my jerkoff film,” says Poole in the doc). Following this rather expensive misstep, Poole headed for San Francisco where his first west coast film was fittingly entitled Moving! (1974). It was also his last with his lover Peter Fisk, who had recently taken up with another man. The breakup marked the beginning of Poole’s longtime dalliance with cocaine, an addiction that would eventually take him out of the business for many years. But in the late 70s, the crash had yet to come, and amidst making a couple more films – among them the self-reflexive Take One (1977) – Poole embarked on one of his many unorthodox endeavours by buying into the kitsch store/hair salon Hot Flash of America, which became a happening hangout canada cialis of the thriving SF gay community, especially in the immediate aftermath of the White Night Riots.

In the period following Milk’s assassination, Poole’s drug abuse increased, but admittedly this part of the film seems a bit underdeveloped and its chronology becomes hard to follow. Poole says it’s a miracle he’s alive, but we never get the sense of the desperation enveloping him at that time because he’s portrayed as still being so functional – mention of his diminishing art collection (at one point he owned EVERY original Warhol ‘Marilyn’) hints to this, but there’s just not enough emphasis on the crippling hell of a crack addiction for it to really grip the viewer. Perhaps it’s just me; I tend to like wallowing, whereas this doc’s strategy is ultimately celebratory – the drugs are a detour, not a center point. Poole moved back to NYC to clean up, and started making movies for the home video market – The Hustlers (1984), Split Image (1984) and the inevitable Boys in the Sand II (1984), all of which did well in the gay market but failed to win him the critical accolades of his first two features.

As with most docs of this type – portraits of bold, ground-breaking characters from the past who’ve spent a long time out of the limelight – the story kind of fizzles out anti-climactically as it rushes through a series of Poole’s less glamorous post-filmmaking jobs, but admittedly this is hard to avoid. The documentary remains essential viewing, especially for anyone who tends to look at porn as a one-note, dead end street – the confluence of art and erotica is a given these days as far as softcore is concerned, but there are very few hardcore pornographers given the distinction of being ‘auteurs’ outside of a small pocket of open-minded film aficionados. But re-staking this ground has been an ongoing campaign for I Always Said Yes director Jim Tushinski. I first became aware of Tushinski through his short film Jan-Michael Vincent is My Muse (2002), a playful paean to the sun-king at the center of the filmmaker’s own adolescent awakening. Next up was That Man: Peter Berlin (2005), his fantastic documentary about photographer, model, porn star and Tom of Finland muse Peter Berlin (one of the documentary’s many fans was, surprisingly, Heathen Scum of The Mentors – between this and their appearance in Paul Morrissey’s Madame Wang’s they’re not doing a very good job of protecting their reputation as homophobes!). Compared to Poole, Berlin was a fairly enigmatic subject, and so Tushinski was able to sidestep any later-life disappointments just because Berlin clearly calculated how emotionally bare he wanted to be. Wakefield Poole was an interview subject in That Man: Peter Berlin, and one senses that the seed was already planted for Poole to get the doc treatment himself.

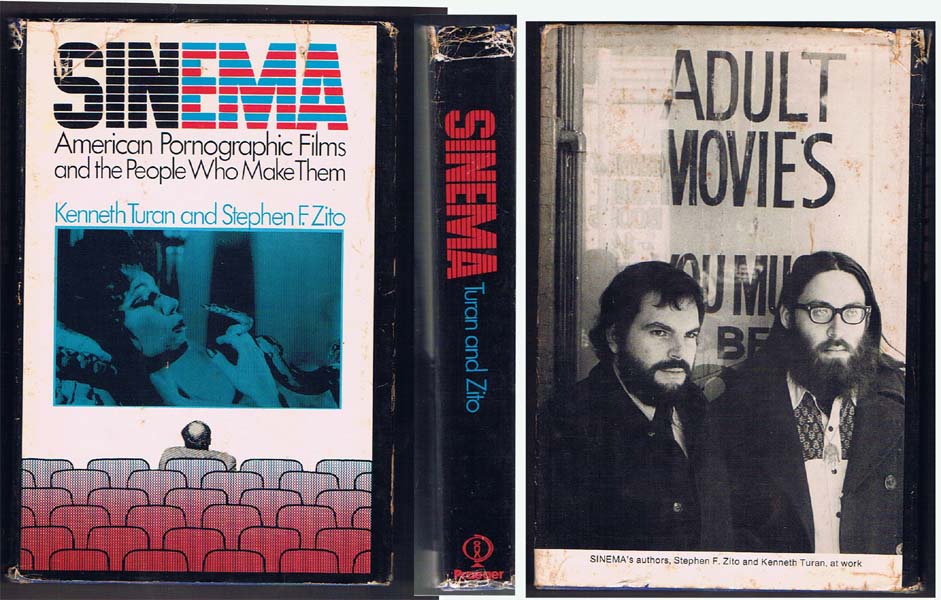

Concurrently with making the doc, Jim Tushinski has overseen the restoration of Wakefield Poole’s back-catalogue. Poole, who admits that he feels overlooked as a canonical filmmaker, is hoping that a new audience will discover his films with the restorations. “I lost my audience because of the AIDS epidemic,” he conceded in an interview for The Projection Booth podcast, and indeed as the doc shows, many of his friends, colleagues and cast members died of AIDS-related illnesses, thus explaining their absence as interviewees. But a new appreciation for Poole’s work has been slowly gathering momentum. A 2011 screening of Poole’s Bijou at my now-defunct microcinema Blue Sunshine was among my favourite screenings there, and was preceded by a teaser for Tushinski’s then-unfinished doc about Poole (then called Dirty Poole, after Poole’s autobiography). I’d read about Poole in Kenneth Turan and Stephen F. Zito’s essential 1974 film book Sinema: American Pornographic Films and the People Who Make Them (which I think I wrestled fellow programmer Lars Nilsen for at a yard sale!), but admittedly I was so anxious to see the film I programmed it sight unseen, which made the screening that much more trepidatious and weird, which I loved.

With the DVD and Blu Ray collectors’ market, many lost or forgotten films have found a new home on the shelves and in the hearts of cult film enthusiasts, and the latest news is that Poole is working with elite restoration company Vinegar Syndrome to produce new releases of his films using the original negatives – “Just like Lawrence of Arabia, or Funny Girl!”

****

FOR MORE INFO ON “I ALWAYS SAID YES” – including how to donate and how to order Wakefield Poole’s autobiography “Dirty Poole” – see the website HERE

FOR MORE INFO ON JIM TUSHINSKI’S OTHER FILMS AND PROJECTS, see his website HERE.

January 23, 2014

January 23, 2014  No Comments

No Comments