COOL GUYS: THE BALLAD OF ASTRON-6

—————————

It all started, fittingly enough, at an event called The Winnipeg Short Film Massacre. The annual DIY horror film contest ran from 2004-2009, organized by Jenn Jozwiak and Jeremy Gillespie – the latter a founding member of what would come to be known as Astron-6. Over its five years of enthusiastic programming, it brought out from the woodwork a surprising number viagra to order of Winnipeg horror fans and filmmakers. “We just wanted to have an event for people to go to on Halloween,” Jeremy explains. The contest provided an essential flipside to what Winnipeg had been known levitra prescription for (and largely continues to be known for), namely experimental and avant garde film. The Winnipeg Short Film Massacre was the only place in town you were likely to see limbs and colloquialisms flying with equal glee and where an appreciation for exploitation cinema history wasn’t considered gauche.[i] “Our first massacre that made us take notice of each other Matt [Kennedy] and I were presenting Ena Lake Blues, Steve [Kostanski] was presenting Fantasy Beyond, and Adam [Brooks] was presenting Addiction is Murder,” explains Conor Sweeney, referring to the 2006 event. “These were the first local movies we’d seen that impacted us at all. Steve’s stop motion work was really unique and impressive, and the character traits he gave the mute puppets reminded me of characters with memorable tics from the movies I loved from the 80’s. Adam’s movie was brutal and genuinely pretty shocking at the time, and he impressed us with some real ingenuitive gore tricks. Steve won first place, Matt and I won second and Adam won third, and this became a trend over the years.”

So while initially competitors, their obvious mutual interests – action, horror, lasers, toilet humor, VHS nostalgia – set the stage for a fruitful collaboration that would be christened Astron-6 Video International. The group has no prescribed mandate; Adam Brooks says that “any of the five of us just make what we want. I think a general style has emerged though, a type of movie that is usually genre-blending and absurd.” The collective’s prolific roster of films bounces freely between genres, and renders the particular talents of its disparate creators into a relatively cohesive whole. “I think I drift towards things that are more psychedelic and absurd, like floating tiger heads,” Jeremy Gillespie offers, in an http://www.spectacularoptical.ca/2021/02/viagra-canada-generic/ attempt to explain how the tastes of each member is represented in their finished work. “I’m usually pushing for any opportunity for things to become surreal or totally silly. Matt and Conor have basically mastered improv and can make anything funny. Adam generally pushes for things to be dark or taboo-destroying, ultimately culminating in suicide. Steve loves monsters and action, and lives in the world of dreams and nightmares.” Rounding out the bromance is Meredith Sweeney (sister of Conor), who Gillespie cites as “the 6th member of Astron-6. She seemed to ‘get it’ more than anyone else and was always fun to have around. Also, Amy Groening is a very talented actress who should probably be avoiding us at all costs.” Conor Sweeney agrees. “They’re awesome, beautiful girls who put up with a lot of fake blood, long shoots, injuries and pig guts because….Well, I don’t know why they do it, but I hope they know how much we appreciate it. If only because our fans drool over them and ensure money in our pockets with whatever we make next.”

When Astron-6 began, Matt Kennedy and Conor Sweeney already had a partnership under the name Greypoint Films[ii], influenced by the likes of Stella and Kids in the Hall. “Matt and I met in high school, and were both outcasts,” Sweeney explains. “One day on a field trip we started talking about Friday the 13th, and whether zombie Jason http://www.spectacularoptical.ca/2021/02/levitra-generic-india/ was better than regular-man Jason. We were fast friends, and were in a couple of musicals together before we decided to start making movies. Our first movie was a cottage slasher called Greypoint. It was 40 minutes long, took a summer to shoot and is humiliating to look back at now. We decided pretty soon after doing shit like Greypoint that we were better at comedy, and started making sketches and doing live comedy instead. Adam saw our short Toby The Alien and started contacting us telling us how much he dug it, and he came to see us perform one night and we kind of became friends from then on.”

The first project to bear the Astron-6 logo was Goreblade, a serialized throwback to the 80s barbarian craze in which a directionless former warrior engages in banal conversations with his countrymen, including a cyclops. “I can still remember that first msn messenger conversation with Adam, when he pitched this idea that he and Jer came up with about a washed-up fantasy hero with a cyclops friend,” recalls Kostanski. “He explained the idea of it being financed by this fake company called Astron-6, and how it would be like a shitty straight-to-vhs type movie, like Deathstalker. I remember being really excited, since my mind was racing with all these pent-up ideas that Adam had triggered. Once the ball got rolling on that, it was hard to stop making movies, since we were all like-minded individuals willing to pitch in and help out on whatever anybody came up with.”

The series is billed as ‘the NEW adventures of Goreblade’, complete with a fictional history (which you can peruse at www.goreblade.com) detailing its early-80s genesis through sequels, cartoons, failed video games and Japanese rip-offs through its new incarnation as a web series. This would mark the beginning of an ongoing trend in the Astron-6 aesthetic, namely an interest in marketing filler – interstitials, logos and commercials – as an art form in itself. “I think the interest in movie marketing peripherals is almost subconscious for me at this point,” Kostanski says. “I’ve been conditioned to feel excitement any time I see the Cannon or New Line Cinema logo, because I’ve seen them so many times before, attached to some of my favourite movies.”

“For us it’s the stuff we grew up on and played with as kids,” Sweeney continues. “It’s fun and nostalgic. In the 80’s and early 90’s kids could buy Terminator 2 toys, Freddy Krueger dolls, Pumpkinhead Topps trading cards and so on. These were hard R-rated movies being advertised to people that couldn’t see them! I had Terminator toys before I ever saw the movie.”

Jeremy Gillespie, who is responsible for many of the poster designs, logos and title sequences (as well as much of the music) for Astron-6 is a major proponent of this unique brand of nostalgia. “I work as a graphic designer and I’ve always been slightly obsessed with the design and aesthetics of the late 70s and early 80s,” he says. “Like most of our generation I grew up watching movies on late night television – Superchannel – and going to hole-in-the-wall video stores. Obviously our films are heavily influenced by that kind of thing, so that’s how I like to imagine people discovering them. Something like the channel lineup at the beginning of Father’s Day places the film in its own alternate universe, adding another layer to the whole idea of this insane lost film. I also like to imagine the ways our films would have been marketed in that era; creating fake ads, trading cards, clunky video games, etc. I love that element of kitschy, garage-sale crap. I love the early 80s Vestron logo most – That’s where I took the inspiration for our name and our original video ident. I’m basically in love with anything created with early video editing equipment and slitscan.”

As a result, many of the Astron-6 films – Fireman, Kris Miss, Lazer Ghosts 2: Return to Laser Cove, You’re Dead – are fake commercials or trailers for unmade films, each with its own design identity that deliberately taps into existing genre marketing stereotypes. But aside from the aesthetic attachment, Matthew Kennedy thinks the interest stems from a more pragmatic source: “I think that most of our fake marketing ideas come from a lack of funding and a lack of energy. If you can’t afford to make a whole movie and don’t have the energy to make a whole movie for no money, why not make a fake advertisement for your movie that highlights all of the best moments?”

As a result, many of the Astron-6 films – Fireman, Kris Miss, Lazer Ghosts 2: Return to Laser Cove, You’re Dead – are fake commercials or trailers for unmade films, each with its own design identity that deliberately taps into existing genre marketing stereotypes. But aside from the aesthetic attachment, Matthew Kennedy thinks the interest stems from a more pragmatic source: “I think that most of our fake marketing ideas come from a lack of funding and a lack of energy. If you can’t afford to make a whole movie and don’t have the energy to make a whole movie for no money, why not make a fake advertisement for your movie that highlights all of the best moments?”

The troupe edged its way into feature filmmaking with several mid-length films such as Punch-Out (a Hardbodies-type comedy centered on a teen with a masochistic compulsion to be punched), Cool Guys (a Hardbodies-type psychedelic beach party murder mystery) and Nobodies (a possibly self-reflexive slacker buddy comedy about two losers who make bad movies), but the first of these – and the first real Astron-6 collaboration – was H.I.Z.: Erection Der Zombie, co-directed by Matt Kennedy and Conor Sweeney and boasting the tagline “When there’s no more room in hell, the dead will fuck at a camp”.

The troupe edged its way into feature filmmaking with several mid-length films such as Punch-Out (a Hardbodies-type comedy centered on a teen with a masochistic compulsion to be punched), Cool Guys (a Hardbodies-type psychedelic beach party murder mystery) and Nobodies (a possibly self-reflexive slacker buddy comedy about two losers who make bad movies), but the first of these – and the first real Astron-6 collaboration – was H.I.Z.: Erection Der Zombie, co-directed by Matt Kennedy and Conor Sweeney and boasting the tagline “When there’s no more room in hell, the dead will fuck at a camp”.

This hilariously dubbed ode to zombie virus epics and summer camp slashers like Friday the 13th, Sleepaway Camp and The Burning also marked the first substantial role for Adam Brooks in front of the screen. “I remember saying we should cast Adam in something after the brief times we had met him,” recalls Sweeney. “I don’t know why, but I knew there was an actor boiling and untapped in him. Clearly a good hunch, as he kills it in everything we do. He had a moustache at the time, and we wrote this pompous idiot head camp counsellor character for him, probably initiated because of that stupid moustache.”

With a gifted DIY FX guy like Steve Kostanski on board, horror has proven fertile ground for Astron-6. In addition to the penile trauma and zombie FX for H.I.Z., Kostanski created the Burial Ground-style zombies for horror comedy Inferno of the Dead, viscera and pyrotechnics for Fireman and Father’s Day, creature prosthetics for his own directorial efforts Insanophenia, Lazer Ghosts 2, Manborg, and the stop-motion and pixellation of Karl – a more rudimentary version of what would become the anarchic and melancholy Heart of Karl.

In Heart of Karl, Matt Kennedy gives an amazing dramatic performance as Karl, a monster whose face is misshapen into a permanent smile like Gwynplaine in The Man Who Laughs (or his direct antecedent, The Joker) and who doesn’t understand why his ‘normal’ brother Max (Conor Sweeney) has abandoned him to an institution. The dark subterranean institution is full of other monsters – which operates as a fitting showcase for Kostanski’s talents – but none have the emotional cognizance of Karl, who struggles to reconcile his ghoulish appearance and abilities with his very human love for his brother. “Heart of Karl was a film that I’d been wanting to make ever since Karl back in 2005,” says Kostanski. “It took me years to sort the idea out in my head, but thankfully I had some real life experiences to draw upon, which I think is what sets it apart from the other movies I’ve directed. Heart of Karl was my last serious effort before I descended into nostalgia again with Manborg, and I’ve been itching to make something in a similar vein ever since. I’m really proud of the sense of dread that Heart of Karl conveys, and I think there’s potential to push it even further. I’m a big fan of building a mythology with each subsequent film too, and that universe is one I have plenty more ideas to throw into.”

“Steve is a deeply, deeply troubled person,” Gillespie confides. “Anyone that’s ever dealt with him on a personal basis can tell you that he is unable to speak or look you in the eye unless you are covered in at least 2-inches of latex makeup. He will move you around like a marionette and tell you which hard surface to fall onto, but that is where communication ends. I like to think of Steve much like Joe Spinell’s character in Maniac. Probably sleeping somewhere surrounded by his friends (mannequins covered in the scalps of innocent women), dreaming up his next project.”

Like most FX artists, Kostanski started as a kid, creating effects using only household items and imagination. “I’d make monster masks out of masking tape, and make little stop motion movies with junk my dad would bring home from work,” he says. “When I was 17 I started corresponding with Dick Smith, and that’s where I learned the basics of prosthetic effects. After that it was a lot of trial and error and learning on the job. In the early days of Astron-6 it was great, because there were always opportunities for me to create some kind of effect, and to always be working on something.”

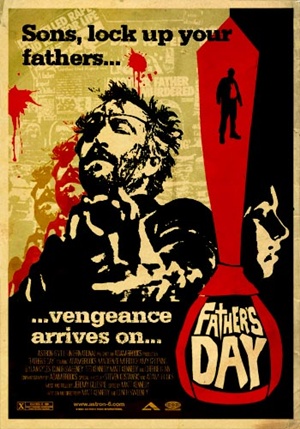

2011 was a breakout year for Astron-6, with Kostanski’s feature Manborg enjoying a major run on the genre festival circuit and the collectively-directed Father’s Day getting massive exposure through a partnership with Troma. After the Father’s Day fake trailer won accolades at the Toronto After Dark Festival, it ended up in the hands of Lloyd Kaufman, who commissioned the collective to make a feature film version, offering up a $10K budget as incentive. “Adam sent our stuff to tons of people hoping they would do promos for a follow-up compilation DVD[iii],” explains Sweeney. “[Lloyd Kaufman’s] assistant Justin charged us $600 for the little promo. After that, they watched our stuff and were blown away. They begged and begged us to make a feature for them, but we were happy making shorts and having fun. Eventually we relented, and told Troma we would make Father’s Day for them. Adam got the $600 back as part of the deal, I hope you’ll be happy to know.”

Father’s Day is a gritty 70s exploitation throwback about a serial rapist who targets fathers, and the eyepatched vigilante who teams up with an albino rent boy and a disillusioned priest to get revenge. The regular Astron-6 stable lets it all hang out in this capricious bid for cult stardom, and despite the film’s more farcical moments, the rape-killer is genuinely disturbing – a fearless, brutish predator not far off from Philip Nahon in Haute Tension. “Matt, Conor and myself were interested in Thriller/They Call Her One Eye when Father’s Day was conceived,” explains Adam Brooks of their contribution to the rape-revenge genre. “We just reversed the gender roles.” Matt Kennedy continues: “We wanted to turn the format on its head and make it very specific at the same time. We decided in about five minutes of joking around about it that the rapist would not only target men, but specifically fathers. We have all seen the female rape-revenge story and we have even seen the male version as seen in Deliverance but we wanted to do something different and also fill the movie with as many sharp turns as possible. Let’s face it, the rape-revenge story is a pretty tired one and most times, a pretty boring one.”

Father’s Day is a gritty 70s exploitation throwback about a serial rapist who targets fathers, and the eyepatched vigilante who teams up with an albino rent boy and a disillusioned priest to get revenge. The regular Astron-6 stable lets it all hang out in this capricious bid for cult stardom, and despite the film’s more farcical moments, the rape-killer is genuinely disturbing – a fearless, brutish predator not far off from Philip Nahon in Haute Tension. “Matt, Conor and myself were interested in Thriller/They Call Her One Eye when Father’s Day was conceived,” explains Adam Brooks of their contribution to the rape-revenge genre. “We just reversed the gender roles.” Matt Kennedy continues: “We wanted to turn the format on its head and make it very specific at the same time. We decided in about five minutes of joking around about it that the rapist would not only target men, but specifically fathers. We have all seen the female rape-revenge story and we have even seen the male version as seen in Deliverance but we wanted to do something different and also fill the movie with as many sharp turns as possible. Let’s face it, the rape-revenge story is a pretty tired one and most times, a pretty boring one.”

The process of bringing this story to life was complicated by the fact that the film was written and directed as an equal collaboration. “It’s five egos and five different creative visions playing a game of tetherball with our movie,” says Sweeney. Brooks concurs: “We have similar sensibilities but writing in a group that large is always hard,” he says. “There is no simple answer as to how we did it, but we basically talked it out until we had an outline, and then emailed the script around the group over and over.” This collage-style approach was sometimes a strain on the plotting, with certain key scenes getting lost and having to be rewritten at the last minute. “When it was decided that we’d all share the duties of writing and directing, I grabbed onto the more fantastical elements in the film and I clung to them for dear life,” admits Kostanski. “I could tell from the beginning that I’d be overruled on everything that didn’t involve gore and monsters, so I stuck with what I knew.”

But the battlescars wrought by the joint scriptwriting efforts were nothing compared to the physical threat posed by the film’s car-related stunts. “I think we tried one of the stunts once,” Kennedy muses. “Actually we filmed the rehearsals. So there was no real rehearsing. We are just lucky to be alive.” Brooks elaborates: “We couldn’t get the vehicles until the day of the shoot, and there was a lot to shoot, and we were racing the sun. I had planned to wear an eyepatch with a hole in it but I’d forgotten to bring it, so I did the jump with a real eyepatch and no depth perception, which was scary. I would gladly have hired professional stuntmen but they were prohibitively expensive, starting at $5000, and our entire budget was $9800, and we didn’t receive the last $3500 until about six months after the movie premiered.”

The deal with Troma was shepherded through by Adam Brooks, and ensured that the Astron-6 brand would get more exposure than ever before. “Troma has a built-in audience, so that’s part of the great deal of working with them,” says Sweeney. “The experience has helped teach us that that the business end of film is cut-throat, mean and no fun. The guys in charge don’t know what’s best creatively for the movie, and they don’t have the filmmakers’ best interests in mind. But Father’s Day will absolutely reach a wider audience because of the Troma association.”

Even though the film was made in Canada using an all-Canadian cast and crew, the Troma association could have some peripheral fallout from a critical perspective – the Canadian arts community is very suspicious of anything with commercial appeal, especially if it bears an American stamp of approval. Many funders such as the Canada Council and various municipal arts councils would see a film like Father’s Day as “not independent” because funds were contributed by an outside party that is considered ‘corporate’ (although anyone who’s ever worked on an actual Troma set and eaten cheese sticks off the floor will beg to differ). Even the early films of our hometown exploitation heroes Cinepix – by all accounts a fiercely independent production company – are not considered “independent” by Canada Council standards. The Winnipeg arts community where Astron-6 first came to prominence is highly dependent on this funding model, and is thus a reflection of these standards. As such, the group hasn’t always felt especially embraced by their filmmaking peers, namely those in the Winnipeg Film Group microcosm.

“You can’t say we haven’t tried,” says Conor. “Look, The Winnipeg Film Group has an image they are trying to hold up, and that’s okay. That image is ‘the avant-garde’. Art house movies. I think that there are great people running that organization who are totally separate from any drama that has gone on between the Film Group and Astron-6. Dave Barber has always been fantastic and is a vitally important figure in the Winnipeg film community. Mike Maryniuk[iv] I like a lot, and he doesn’t fall into the clique mentality that so many of the rest do. As for other reasons we operate in our own small group, we just don’t connect with any other filmmakers in the city. We were lucky to have even found four other guys as weird as we were who loved VHS, David Lynch, underground comedy and nostalgia as much the rest of us.”

“I think there are lots of great things about the Winnipeg community,” offers Kennedy, “but there is also a lot of ego and bureaucracy. People like Guy Maddin, Dave Barber, John Kozak[v] and Greg Klymkiw have been nothing but supportive and helpful to us as filmmakers. Guy Maddin forwarded a lot of the terrific actors we worked with in Father’s Day to us and John has invited us to speak at the University of Winnipeg Film Fest as a special guest. Other people in the city however, have only tried to keep us down. The Winnipeg Film commission for example tried to shut our movie down after claiming they would help us with our shoot.”

With the recent success of Father’s Day (Best Film winner at the 2011 Toronto After Dark Festival where it premiered) and Manborg, and all the members now living in different cities, it seems that Astron-6 has entered a new phase that will see their collaboration go national. And both films are still going strong on the fest circuit: the next stop for Steve Kostanski as of this writing is the Imagine Festival in Amsterdam, where Manborg and Father’s Day are both featured, then Adam Brooks and Conor Sweeney hit the horror honkytonk in May for Texas Frightmare Weekend. “I can’t wait,” says Sweeney. “Ideally I leave there with Danielle Harris’ phone number. I could die happy if I had a date with that woman.”

[i] Even though Winnipeg filmmakers like Guy Maddin, John Paizs and Jaimz Asmundson dabble in the lexicon of exploitation cinema at times through camp explorations of melodrama, film noir and/or ghost stories, the arts community of Winnipeg in general doesn’t often engage directly with this facet of cinema or see it as historically important.

[ii] Dave Barber programmed a Greypoint Films retrospective at The Winnipeg Film Group’s Cinematheque in 2007, and some of the Astron-6 Films still carry the Greypoint Films imprint.

[iii] To follow up the Astron-6: Year One DVD which they self-released in 2008.

[iv] Filmmaker and former Winnipeg Film Group Production Coordinator

[v] University of Winnipeg Professor, director of underrated JD film Hell Bent (1994) and the namesake of Adam Brooks’ character in Ghost Killers. Not to be confused with the kangaroo detective on TVOntario’s Math Patrol.

May 1, 2012

May 1, 2012  No Comments

No Comments